Sujit Saraf in New Delhi recently. Photo: Shireen Quadri

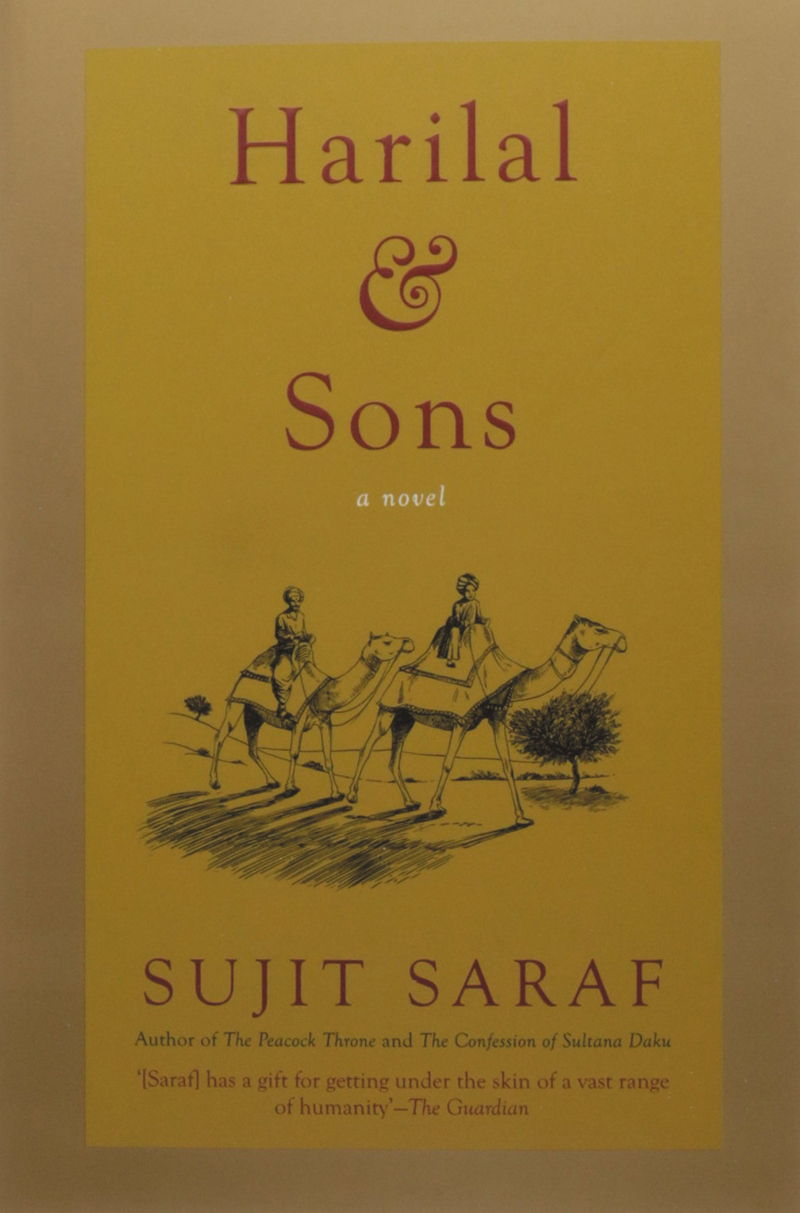

Sujit Saraf’s latest novel, Harilal & Sons, is based on his grandfather’s life. His 2009 novel, The Confession of Sultana Daku, is being adapted into a film featuring Nawazuddin Siddiqui

Sujit Saraf works at Infosys in the US in the day and does theatre at night. Apart from his fulltime job at Infosys, he is also an author, a playwright, an actor, director, founder and creative head of the Indian theatre company Naataka, for Silicon Valley’s large South Asian population.

Saraf was born in Bihar and studied in IIT and University of California, Berkeley. Saraf has written three novels — Limbo (1994), The Peacock Throne (2007) and The Confession of Sultana Daku (2009), which is also being adapted into a feature film starring Nawazuddin Siddiqui. Harilal & Sons: A Novel, his latest, published by Speaking Tiger Books, is the story of Harilal Tibrewal, who sets up Harilal and Sons, a shop selling jute, cotton, spices, rice, cigarettes and soap, that grows into a large enterprise. It is also the sweeping tale of his two wives and ever-burgeoning family of sons, daughters, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren. The novel, which opens in 1899 in the north western corner of British India where the Chhappaniya famine stalks the desert region of Shekhavati, ends in 1972, as eighty-five-year-old Hari lies dying in the great mansion that he built but never actually lived in.

Excerpts from an interview:

THE PUNCH: The trigger for this novel was your grandfather’s story. However, though it’s a personal story, there’s this whole historical dimension to it. Did you want this to be a book about Marwaris?

SUJIT SARAF: I never met my grandfather. He died nine years before I was born. And this is a very Indian thing: People do not keep good records of what happened even in their own family. It’s cliché to say Indians have no sense of history because Indians are living history. There is this well-known account of people in Ujjain who are living in heritage buildings and the Archaeological Survey of India or some historians don’t want them to mess with that buildings, but they live in them, use them, and damage them. It’s very common for us to disregard our own history. So, whenever I would ask a question about my grandfather, I was surprised to note that most people didn’t know anything about him. My father could barely answer any question because my grandfather was 55 when my father was born. So, perhaps there was no connection between father and son. And there is this constraint that once people have passed away, we only speak well of them. So, everything that was spoken about him was couched in platitudes — that he was a wonderful man, a very religious man and the like. I always wanted to tell his story and I was very fortunate as one of my cousins had made a one-hour recording of an interview with my grandfather shortly before he died. I’m the youngest son of the youngest son. So, the age difference between me and my grandfather is great.

I’ve always wanted to write a book about him which can actually be seen as a book about Marwaris. He’s emblematic of the wider world of Marwaris who trade and live in a very conservative fashion and acquire wealth over generations and never spend it. When writing the book, since I did not know the man himself, the human being in the novel is entirely how I imagine. I actually don’t know what kind of a person he was. I broadly traced the outline of his story and it became as much a story of Marwaris as of the man himself. Naturally, I made changes here and there. So, aside from the general historical research that one must do while writing a historical novel, I travelled to Bangladesh. I went to the usual places — Rajasthan, Mumbai, Kolkata — and interviewed a very large number of people, some of whom have passed away because they were in their 80s and 90s. Many of them were not very educated so they do not situate my grandfather’s life in the historical context, the way I do. They will not talk of the non-cooperation movement. I took their local reminiscences and situated them in a context.

THE PUNCH: Tell us about the research for the novel.

SUJIT SARAF: I was already familiar with the broad contours of Indian history. I did have to dig up a fair amount of material from some obscure libraries in Kolkata filled with weird Marwari books — books that enjoyed limited circulation. A rich Marwari Seth will decide a book has to be written about his life. It has to be largely be hagiography. He’ll talk about how he came from Shekhawati and made a lot of money and 200 copies will be printed and one copy will be placed in a particular obscure library in Calcutta. I was fortunate to have access to many such libraries. Beyond that, I didn’t have to do much research. Everybody knows what happened in 1947 and 1962 and 1971. So, I combined personal accounts of Marwari seths with what we all know about Indian history.

Rather than situating his life in history, I often work the other way. So, I know exactly when the Japanese, for instance, bombed Kolkata. They only bombed it once or twice. So, I made sure that the particular wedding of one of his son’s happens on that day. Now, I have no clue when that wedding happened. It may have happened with two or three years of that date. So, I exploited that bombing and deliberately brought a wedding to Kolkata, thus bringing all the characters in the novel and having them see the wedding. I know that in January 1934, there was this great Bihar earthquake. Gandhiji aslo went there. There was much destruction. And I know it was felt in Kolkata also. So, I made sure that a particular wedding also happened on that day. I often situated him in history by twisting some dates, used historical markers and laid out stories from marker to marker.

There is also a certain sentimental attachment that I have to the subject because I’m writing, in a way, about myself. I sneaked in myself also. There is a very oblique reference to a little boy towards the end of the book which is actually me. I did change around names and details naturally because for everybody in the novel, there exists a human being and in most cases that person is related to me. You may have noticed the portrait of the man is rather sympathetic after all. It’s not an impersonal novel. It’s in a way my story.

THE PUNCH: You also write that your grandfather, in a way, never retired, settling for the third phase of his life — vanaprastha — he was told about by Masterji.

SUJIT SARAF: It’s very typical in conversations in my family. It’s very commonly said that you are first a brahmachari (student), then grihastha (householder), then you go for vanaprastha (retirement). But it is honoured in the flouting. My father died a grihastha; he died at his desk doing his accounts worrying about a robbery in our family that had happened that very morning. He never had the privilege of going into vanaprastha. So, everybody speaks about it. But, in my community, I don’t think there are many who truly feel this detachment and to the best of my knowledge the actual man did not feel. They keep talking about this detachment, but businessmen, or for that matter anybody, don’t actually follow Varnashram Dharam. So, I wish my father had done it, my grandfather partially achieved it from some accounts I have heard. The rest I imagined. I also left it a little ambiguous. In the very last lines of the book, he complains about a tap which is dripping. He is obsessed with water wastage, having survived the Chappaniya famine of his childhood and he does wonder if he has travelled into vanaprastha. He’s actually not hundred percent certain because he even talks about repaying a loan. These are all entanglements. In the novel, Masterji tells us that for a baniya to pass into sanyas is unheard of. So, he has no hope of ever reaching the fourth stage. I would like to pass at least into the third stage after a certain age. I feel that my father was accosted and surprised by death and did not have the time to step away in a dignified fashion. So, it’ll be nice to step away in a dignified fashion and prepare to die. It’s a Hindu ideal and Marwaris speak about it all the time. All their pundits and Satyanarayan puja, they speak about this detachment that must arise but I don’t think it comes. We see that people in their 70s and 80s are clinging to power and money and buildings and family and buying and selling.

THE PUNCH: Did you primarily have Indians as your readership on mind when you were working on this?

SUJIT SARAF: Perhaps it may have been written with a western sensibility since I live in the West but, certainly, it’s written in some sense by an insider who has been on the outside also. But the outlook of the novel is entirely Harilal’s outlook. When he expresses his preference for light skin, when he clearly expresses a preference for boys over girls, when he takes pride in the fact that a life well lived is life lived with a large family — these are very Indian ideas. The outlook of the novel is Indian. The language is English.

Page

Donate Now

Comments

*Comments will be moderated