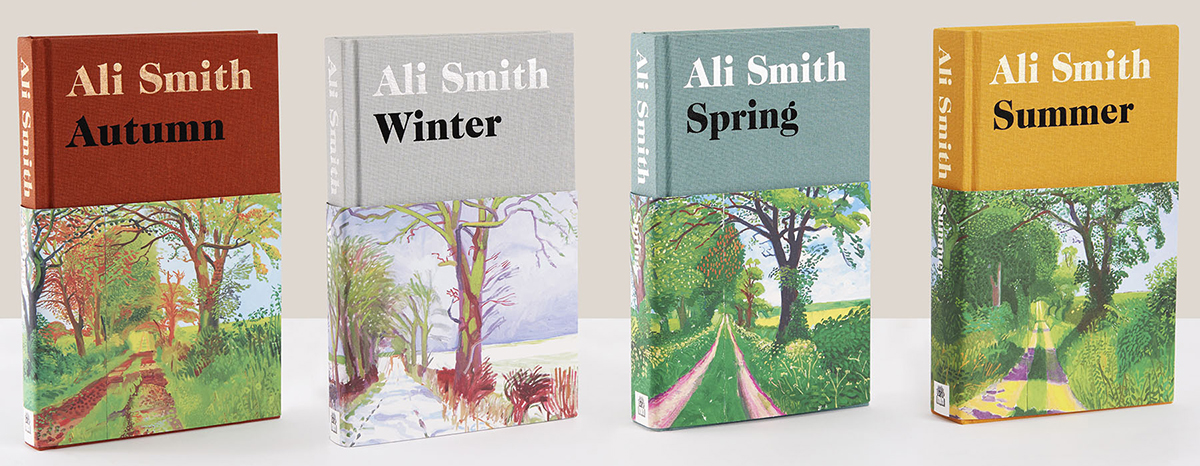

Scottish writer Ali Smith. Photo courtesy: nationalcentreforwriting.org.uk/

Critical reflection is the one important tool that we need to develop if we are to make sense of the increasingly meaningless world. While reading Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet, one realizes that the whole exercise was to see the connections when there appear to be none. Smith wrote the quartet so that we could see that, in fact, we are all one.

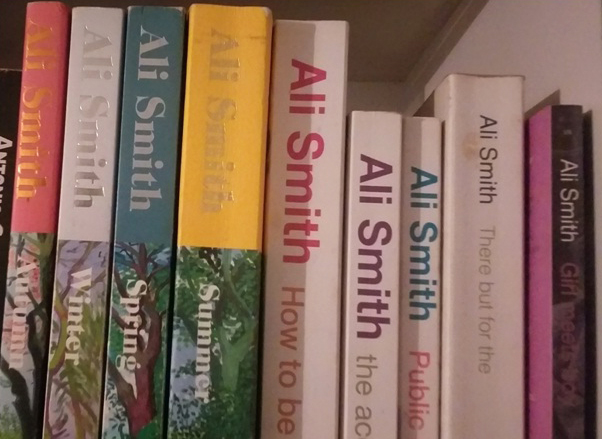

“It’s because you read these Muslim authors,” my cousin said, running her forefinger up and down in the air in front of my stack of books by this Scottish woman writer. Ali Smith. The name had led my cousin to identify the ‘cause’ of my time spent at Shaheen Bagh, my vocal criticism of the now heightened ‘othering’ of a minority community, and other such ‘ailments’ that I was afflicted with. This I tell you, so that you have an idea of my location, as I invite you — you who have read the many reviews, many excellent analyses of the plots, of her language, by experts — to hear what these books meant to me. The degree of understanding, even recognition, in my immediate world, of the author whose latest work I am about to discuss. Literally the location at which I read the quartet alone — away from book clubs, literary discussions, work-associations with the western world — at the dining table very near the book shelf at which the cousin-criticism was wiggled.

Hello again, Mr. Gluck, she says. Oh hello, he says. Thought it’d be you. Good. Nice to see you. What you reading?

When I was reading the quartet, I was witnessing an experiment — in topicality, in immediacy. Many questioned Smith’s choice in writing of the present time, literally as it happened. Mainly of the present in the UK. How could it be of any significance to anyone outside the UK? Why should others read it? However, when one has read them, one realizes that they are, in fact, about the whole world. Political changes that have taken place in the time that the quartet is set in, written in, have not occurred in isolation. Recent shifts towards the Right, the emergence of powerful egoistical leaders, suppression of protesting voices, reinforcement of borders, demonization of minorities and migrants have occurred almost simultaneously in countries geographically distant. Oppressive regimes, as if supporting each other, make the world conducive for oppression.

In retrospect, I find that reading the novels, in fact, gave me insights into what we in India went through in the same period. Sometimes, when you are in a situation, you lose objectivity. Here, I do not mean objectivity, as opposed to subjectivity — to look at politics, at history in-the-making, with my own personal point of view. But the distance required to look at one’s own situation, perceive one’s own country. The lightness, the playfulness of the seemingly superficial story-telling that the novels offered was just what I needed. To relate to, to empathise with, to identify with, without getting bogged down. The lightheartedness of Smith’s writing served a purpose.

Even in that lightness, Smith’s characters are complex, layered. Human. Sometimes objectionable. Staying with them, finding myself liking them despite their flaws, forced me to ask myself questions about the assumptions, maybe even prejudices that I myself carried. Critical reflection is the one important tool that we need to develop if we are to make sense of the increasingly meaningless world. I related with the novels, with what was happening in them, and wanted to try and share this personal experience. I may sound vague. It may seem as if there is actually no connection whatsoever. That the associations are something I made up. So be it. For that is what the quartet told me. That is what one realizes while reading the last book. That the whole exercise was to see the connections when there appear to be none. Ali Smith wrote the quartet so that we could see that, in fact, we are all one.

I went back to Autumn (2016) after reading Summer (2020). Someday, I will read the entire quartet in the order in which Smith wrote them. Then, I will really know what a vast, ambitious work this is. In Summer, if a young woman is caring for a 103-year-old dying man, you need to go back to Autumn to see how a little child met this strange old man, who became a kind of grandfather figure, more importantly, a friend.

In my beginning is my end. From East Coker. A part of TS Eliot’s Four Quartets, which was published in October 1943. Seventy-three years before Ali’s quartet. No review of Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet, has mentioned T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets which came out, again, in another difficult time of discrimination, destruction, displacement and death — the Second World War. But there it is, another quartet, another art project — the great TS Eliot trying to provide solace in a time of pain.

And so,

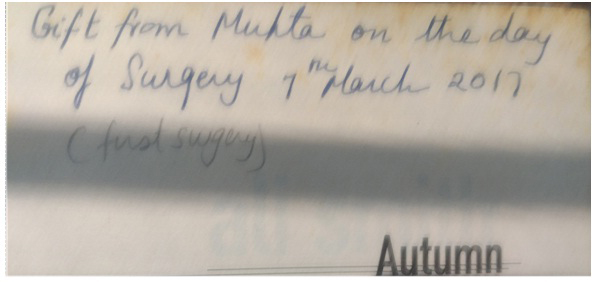

Book 1: Autumn, published on October 20, 2016. I read it only in the second week of March. A note made by me on the first page hints at the possible reason for this delay. Personal reasons that we need not delve into.

However, for a more public reason, anyway, we Indians were not very much in the mood of buying books in the month Autumn came out. It would seem that the English-reading middle class may not have been affected by demonetisation, but the way it was sprung upon us, was shocking. In an 8 pm national telecast on November 8, 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that the notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 denomination would no longer be valid from midnight, four hours after the surprise telecast. Sabziwallahs, farmers, women workers, workers in unorganized labour, all vulnerable sections of the population, were ruined. Not only was it unfair to the weakest, but it did not achieve what it said it set out to. A grand aim, in this case, the unearthing of ‘black money’, towards which we were all to bear certain inconveniences — for some, certain ruin — which was not achieved. Only the rich were unaffected. The ones who, in fact, had ‘black’ money. The rest of us suffered. Some of us protested. In vain.

Autumn was the first post-Brexit novel. Smith wrote:

“All across the country, there was misery and rejoicing…. and

All across the country people felt it was the wrong thing. All across the country, people felt it was the right thing. All across the country, people felt they’d really lost… and

All across the country, the haves and the have nots stayed the same. All across the country, the usual tiny per cent of the people made their money out of the usual huge per cent of the people. All across the country money money money money. All across the country no money no money no money no money.”

Book 2: Winter, published on November 2, 2017.

“The bitch deserved to die.” Jubilant tweets that followed the assassination of Gauri Lankesh, a journalist. That was what I remember from 2017, the fear I felt, the sadness. I do not recall the details of her death, but remember that her last editorial had been about fake news. At the condolence meeting, a journalist from Hindi TV spoke of TV anchors who kept the citizens distracted by and engaged in sensationalised trivial issues, night after night. Three years after that, today, this phenomenon has reached alarming heights. In Winter, Ali also discusses the time “when pre-planned theatre is replacing politics, (she said,) and we are propelled into shock mode, trained to wait for whatever the next shock will be, served up shock on a 24 hour newsfeed like we’re infants living from nipple to sleep to nipple to sleep.”

In Winter, Smith draws on Dickens, (A Christmas Carol, 1843). At the end of the quartet, while discussing the quick-publishing exercise, she will cite the example of Dickens as someone who wrote as he published — in serial form in a newspaper.

Along with Dickens, in Winter, we will also find Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (1611).

“about a kingdom subsumed in chaos, lies, power mongering, division and a great deal of poisoning and self-poisoning”

Winter, for me, is the story of Iris (who is not Ali’s protagonist), an activist who protests (like the journalist we lost) against nuclear weapons, against fascism, and her sister (the ‘main character’) who is haunted. The story is set in Cornwall. Cornwall’s patron saint is Newlina. She was beheaded for disobeying. But she picked up her head and walked. The theme of protests runs through the book.

But sometimes we are not allowed to protest and must contain the anger and bear it. Personally, this was a time of changes in mobility for me. For this year, I add in pencil, to the inscription on Autumn, the words — first surgery. First. For there was a second surgery to correct the first (botched) one.

Thank you, Ali, for the hope you give me on page 66-

That’s what winter is: an exercise in remembering how to still yourself then how to pliantly come back to life again.

Book 3: Spring, published on March 28, 2019.

It’s called Spring, but it is darker than the first two books. I read it sometime in July. July brings dark clouds. The clouds will burst to submerge everything. Nothing will be the same. Those who protest will find themselves being questioned, in the middle of strange stories that they did not write. There are also protesting cries for a beautiful green-eyed child of shepherds. The God inside the temple could not protect her from the priest’s new method of scaring away the sheep. The God could not hear her. After she was killed, the screams got converted to a hundred slogans. Did you hear our slogans, Ali, for you wrote-

Do you know, (Alda says,) that the word slogan was a Gaelic word originally? Your man there saying the word reminded me. From the words for shout of the army.

Sluagh-ghairm. Slogan.

It means war cry.

Tell you all you need to know about what slogans are always about, whether it's take back control or leave means leave or don't buy from jews or I'm lovin' it or just do it, or every little helps

Yes, Ali; you know.

and

kids down the mines right now..

They are mining the cobalt for the environmentally sound electric cars."

All this, in your book full of so much fun.

Hope.

Since that's what love is, this matter of hopeful travel against the usual deeply troubling odds

While this book was being written, people were suffocating inside tankers, babies — dead babies — were being washed ashore. In India, 40,70,707 people did not make it to a list. Who are they? Are they not Indians? Why do people migrate? What do they want? Why are they so unwanted?

Don’t be calling it migrant crisis, (Paddy said.) I’ve told you a million times. It’s people. It’s an individual person crossing the world against the odds. Multiplied by 60 million, all individual people all crossing the world, against odds that worsen by the day. Migrant crisis. And you the son of a migrant.

It is evident that Smith has researched thoroughly about the day-to-day treatment and living conditions of the detainees. All this she can bear to write about, only by resorting to black bitter humour, and by dwelling on details like grammar, seemingly ordinary conversations which we read through, only to discover much later that they have left a mark on our minds, that they drive home the ‘ordinariness’, the ‘everyday’ of incarceration.

Much later, when we come across news of children separated from migrant parents, and in India, when we see hordes of migrants walking home next year.

I’ve done three years in here for the crime of being a migrant, a deet said to her. If you’re keeping people here this long, you may as well let us do something. We could take a degree. Do a useful thing.

Useful? She said. A degree? Ho hoho.

I crossed the world to come here, to ask you for help, a Kurdish deet said to her. And you locked me in this cell. Now I sleep every night in a toilet with some person I don’t know, whose religion I don’t share.

It’s a room not a cell. And you’re lucky you’ve got anywhere to sleep at all, she said.

One deet was lying on his back on the floor in his room with his head close to the toilet pan. He was staring from this angle upside down at something through the bars and the perspex high above his head.

Why can’t we open window in this prison? He said.

Open A window, she said. And this isn’t a prison, it’s a purpose-built Immigration Removal Centre with a prison design.

When you’re live in Immigration Removal Centre with a prison design, you dream air, the deet said.

When you’re living, she said. Or when you live. You dream About air.

Hero was his name.

Hero will not remain so isolated for long. For Hero, in the next book, will receive a letter. From Sacha Greenslaw. But wait a minute. That’s in the next book.

Book 4: Summer, published on July 2, 2020.

For four years, each of these compassionate, intelligent books had been like a painting I placed next to the framework through which I tried to make sense of new regimes, unprecedented humanitarian crises, incidents and judgements that shook the very foundations of what I knew as my country.

I do not say that the books provided me with a frame, but that they were art placed right next to the reality. Reality that changed so rapidly, that one began to question the usefulness, the worth of what little one did.

What difference would this make? The books are art — full of meaning. The art was created far away from here, but helped in making sense of my life — the changes in the world around me, and the change that illness brought about in me. As I have discussed, there were similarities between what Smith wrote about, and what was happening in my immediate surroundings. I clutched at self-drawn parallels for support. And, then, beyond just similarities, something happened, rather the same thing happened to all of us.

Summer is the first serious novel that speaks of the pandemic, of lockdowns. The content of the novel and my reality finally coincide. United in what though? In Isolation? No. Become one. As if the journey of my reading the quartet was for the satisfaction of this coming together. In many ways, the plots dovetail into the ending. All our people — Charlotte and Art, Grace, Daniel, Iris — everybody is here. We can either come to know — and I do not say 'find out', but come to know — what had happened to them in the past that was even before when we met them in the previous books, or be reassured of how they ended up.

Photo: nadi (Dr Manasee Palshikar)

Why so much discussion over a letterbox, even about the word Letterbox, you wonder. Then you see how, she is using humour to speak of marginalisation, exclusion, racism, hyper-nationalism, of borders. The iconic letterbox has been built up, so to speak, to tell us, “In summer 2018, after a disagreement with the then UK prime minister, a backbencher MP who’d resigned from his post as Foreign Secretary — a man who just a year later would son become UK prime minister himself — wrote an article which he published in the Evening Standard where he stated that though he personally declared himself not intolerant enough to believe Muslim women who wore full face veil burqas should be banned from wearing what their religion often required of them, all the same he thought it ridiculous of Muslim women to choose to go around looking like letterboxes. Their choice of clothing, he said, didn’t just make them resemble letterboxes but also bank robbers. He was paid 275,000 pounds for the article, which he wrote in breach of ministerial code, and which was cited in the following days as the reason for the quadrupling of anti-Muslim attacks and incidents in the UK. In the run-up to the UK general elections of 2019, he repeatedly refused to grant that there had been anything harmful, irresponsible, or troubling about his rhetoric.”

(A person whose speech during a VIP visit to India led to inciting of attacks on the members of a particular community, was acquitted. Would we dare to write about that in our fiction in the way Smith has written about their prime minister? This complex layered quartet is a project of literature, but a brave act of activism. The completion of the quartet is an inspiration.

And the above passage continues. And, here, Smith is actually mentioning India!

This was a time when attacks on people with Islamic beliefs across the world were rising with first America then India closing borders to Muslims, India legislating against Muslims, and orchestrating attacks, beatings, lynchings, arrests and killings of Muslims and the recent cordoning off of the whole of Kashmir, alongside a massive coordinated, international right-wing militarization, and in China, a simultaneous instigation of ‘re-education’ detention centres for Muslims.

All similar, all connected. The plot, too. Similarities between characters. Connections across geographies, across time.

Smith tells us that the word Summer derives from the Old English sumor, and from the proto-Indo European root sam, meaning both one and together. Suddenly, it all makes sense to me. What is important now, in the pandemic, is to know that even when isolated, we are unified, sharing the very reason for our isolation.

Summer is about that. In fact, I realise how all the books have dovetailed now at the end to tell us that there are connections even when the world seems disjointed.

We know sam in India — in our Hindustani classical music. Sam is the point of meeting, of resolution. A pivotal point that all movements, and melodies, aspire to meet at.

A brother and sister duo — in the present time — not getting along at all — opposite politically — but understand and love each other the most. Another brother sister duo in WW2, writing letters to each other, but destroying the letters, a mother and daughter who make fun of each other and hurt for each other. It seems all mixed up, but actually is all connected. All making meaning together.

Sorrow, sorrow. Joy, joy. Woven together like reeds in moonlight, wrote Virginia Woolf in a 1921 short story — again a connection — “The String Quartet.”

Woven together, inextricably commingled, bound in pain and strewn in sorrow — crash!

Exactly.

and from me Ali, just

!

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated