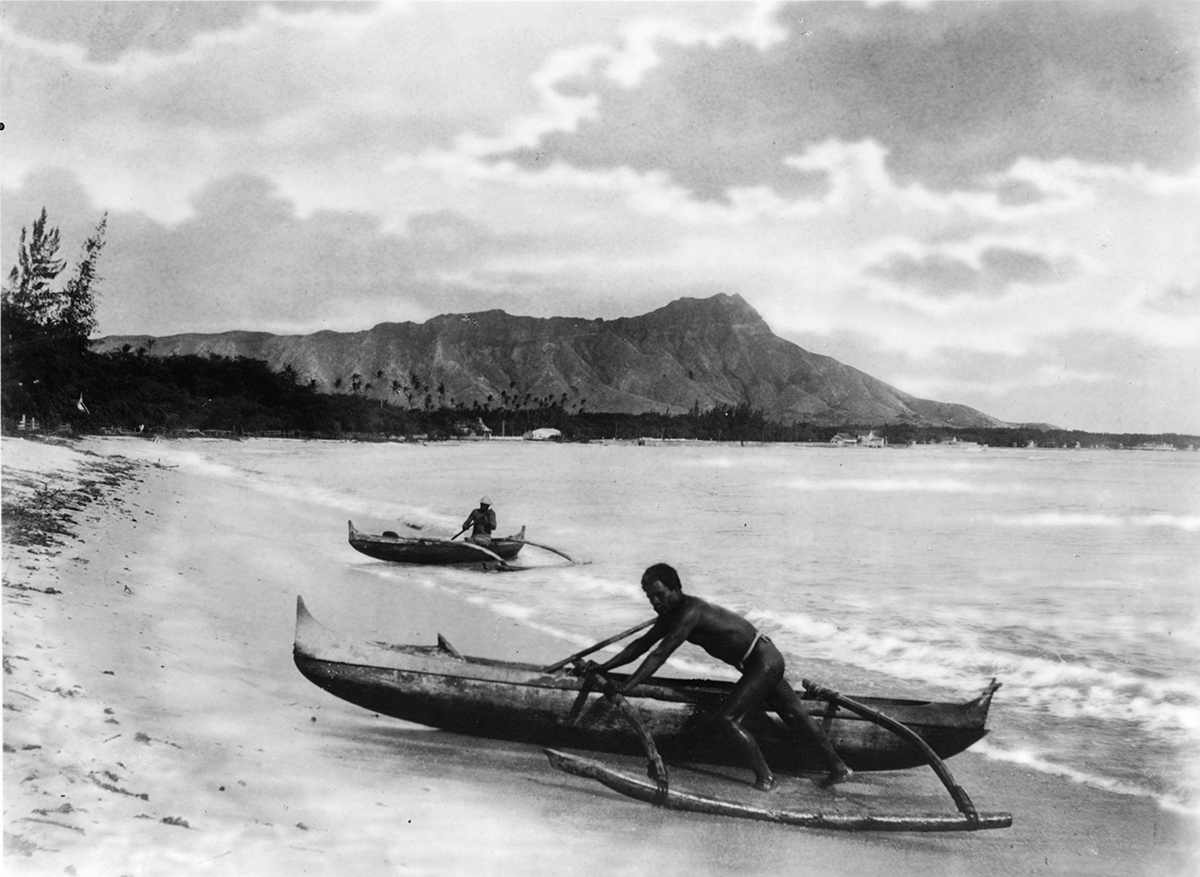

Polynesians with outrigger canoes at Waikiki beach, Oahu Island, early 20th century. Photo: Wikipedia

In the late 19th and early 20th century American anthropologists travelled to Polynesia and wrote vivid accounts of their encounters with strange cultures and practices. In ‘Life in the Trobriand Islands’, Margaret Mead wrote of a quaint culture with outmoded forms of family rituals. “I noticed”, she wrote, over the course of 35 years, “that adult couples engaged in fertility rites and produced children that they felt responsible for, even sending them to small institutions called schools near their own houses. Their bamboo homes were neatly decorated with family pictures and still life paintings by Gauguin. The natives practised an unusual form of pacifism. Every time the French exploded an underwater nuclear device, they smiled to themselves and gave lectures on harmony at the local university.” Intellectually stimulated, though emotionally disturbed, Mead eventually returned to New York. Reverse traffic began to flow in the 21st century.

In certain Polynesian cultures the mother-in-law will cook a special meal for her son-in-law but forget to invite him. Or do so only after the meal is over. This often creates friction between the older members of the Olongo tribes in Eastern New Caledonia who are carnivorous and often eat the mother-in-law during the marriage ceremony itself. The Olongo are extremely superstitious and insist that only Polynesian spices be used for cooking the mother-in-law. The recipe from the ancient tribal text called 101 Easy Dishes of Polynesia, now available as an e-book, maintains that slow hot oil cooking is preferable to microwave — because it ‘preserves the juices and the bile’ especially if the meat is old.

Anthropologists from Polynesia found similar strange customs amongst Wall Street accountants in a far off place called New York in Eastern North America. Here newly married couples were actually ashamed of their relatives and used all sorts of elaborate social rituals to avoid their company. In small tribal communities on an insulated far-flung island called Long Island, Polynesian social anthropologist Dr. Suma Odombe found strange rituals which even forbade the new bridegroom to have regular intercourse with his mother-in-law.

Odombe stayed with a ‘family’ in a place called ‘Great Neck’, considered by many an upscale neighborhood (‘I couldn’t understand what was upscale about it’ he said. ‘Most houses were large and set away in their own compounds. In Bora Bora, when people become rich, they abandon their homes and move in with each other’). What surprised him was the complete lack of social interaction amongst members of the same family. ‘In the three weeks that I spent there,’ Odombe wrote in the Polynesian Review, ‘not once did I see the father having sex with his own daughter, even though it was obvious to me that both had reached puberty and both seemed attracted to each other’. It appeared that an unwritten law of sexual prohibition applied to intercourse between members of the same family.

While the actual significance of such avoidances between relatives was difficult to gauge as anything more than a protective measure against accidental child birth, the real reasons could only be social taboos and inhibitions. ‘I found many women even covered up their breasts in a special garment they called ‘bra’— a strange article made of cotton with two cup-like features that clasped the breasts and kept them hidden from view’. Odombe who took several rides on a ‘Number 7 commuter train’ found to his surprise no man suckling or fondling the breasts of women sitting within easy reach of each other’. In fact, most people rarely spoke to each other, keeping their faces hidden behind newspapers.

The reason for such anti-social behaviour was unclear to Odombe, and he set it aside as ‘human touch being unclean’, and could provoke the wrath of the Skin God. What did disturb his sensibilities as a human being and a Doctorate in Anthropology from Micronesia University, South Campus, was the misunderstood aspect of beauty in Western culture. Unlike the Tora Bora tribal cult where the skull of newborn females is placed in a bamboo press to reduce the size of the forehead, local women in the Long Island were found to have heads as large as their male counterparts. This aspect of human beauty — or lack thereof — was astounding to Odombe, whose own exceptionally beautiful wives have virtually no forehead, and the eyebrows form the hairline of their faces. ‘I could not see how the perfection of the human body and face should be constrained by such obvious limitations’, he lamented in an interview to the Journal of Racial Taxonomy. ‘The absence of a forehead in a woman is so crucial a quality of beauty, I found myself undervaluing my hostess because this important cultural aspect seemed to be missing.

In advanced tribal societies like the Canugas in Eastern Samoa, mutilation of genitals is a common practice to avoid incest between siblings. I bought up the subject with my Jewish hostess Margaret, and was horrified to learn that all family members had their genitalia intact. ‘Many males on Long Island still retain their testicles even after reaching puberty’, Margaret explained. This, Odombe assumed, was based on social and historic assumptions which place no customary restrictions on the tribe, allowing complete freedom to conduct incest within families, even encouraging intercourse between the patriarchal male and his spouse. Though it may be easy to explain this deviation in linguistic terms, the motivation for these practices reveals a far greater complexity, and may have its origin in another deviant domestic ritual. The separation of food consumption from its natural bodily expulsion was noticed by Dr. Odombe who found in Long Island houses not just two entirely separate arenas for the functions, but also separate timings in which to perform them, each with its own mysterious view of privacy. ‘In Tora Bora we eat and defecate at the same time and often carry on a conversation about local politics or who is likely to succeed in the upcoming elections for Chief and Deputy Chief. Eating an elaborate soufflé and removing it immediately from the body can be done in one go. It hardly seems sensible to create complex rituals and secluded private quarters for a task that takes up so much time in the day, and then comes up again a few hours later.’

Many of the women that Dr. Odombe met during his stay on Long Island, he sensed, belonged to a wide variety of diverse tribal groups. Some had possibly been captured in battle from another local clan or were a byproduct of a recent migration from a nearby rural area called ‘Greenwich Village’. In a bar on the southern tip of another island called Manhattan, Dr. Odombe noticed many men accosting woman of a different gender and using alcoholic beverages as a lure to a sexual encounter. What surprised the noted anthropologist was the fact that many of those who went off with each other had no inkling of the other’s tribal links or hereditary background. ‘In my home, the penalty of intercourse with an unknown person is usually death, after which there is a long rehab process before you get accepted into society’.

After a long hot summer, Dr. Odombe returned to his native Tora Bora, carrying with him not only the existential baggage of a strange new culture, but also a new Jewish wife, Margaret Odombe, his Long Island hostess who he married at the Kennedy Airport lounge on his last day in New York. The two lived several happy years in the bamboo family home on Tora Bora’s swanky beachfront where a century earlier Gauguin had made his home. Then, one special day, the day of the marriage of Dr. Odombe’s youngest daughter, Margaret, was specially spiced and lathered with oil for the occasion, cooked at high heat, and served in small portions to the wedding guests. The touching love story is still available to the public in Annals of Polynesian Anthropology, Vol. 13.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated