Basu’s fiction is an unflinching reminder to his readers across the English-speaking world that the ‘children of men’ and ‘of war’ are not just ours, or theirs

Veteran writers have in the not so distant past given us strikingly original, expansive retellings of the tangled history of humankind. When the same authors turn, with barely concealed urgency, to writing the contemporary; when they choose not to wait for the dust of the present to have settled, it is probably time for the reader to sit up and take note of a crucial turn in the life of the Indian novel in English. The storytellers in question are probably thinking that waiting would be an unaffordable luxury given the unhappy convergence of planetary crises here and now. The corresponding return to the simplicity of stories, either a single one or one of several lives intersecting at a single coordinate of national or global significance, suggests the felt need to reach the general reader in this perceived moment of reckoning.

In An Ideal World expertly loops our attention around the story of one family of three in the eye of one local storm. Yet, just as in the unfolding menace of climate change, we see a lateral simultaneity of expectedly unexpected local upheavals, so also in Kunal Basu’s story of a metropolis and a small town twinned by a certain concatenation of little personal moves and larger political events. In this case, the little move is the familiar matter of a young adult going to a regional private engineering college for his degree studies. Basu knowingly inverts the trope of the naive small town migrant arriving in the troubled melting-pot that is the big city. The mesh is more widespread now, and the boundary between the margin and the centre is blurred in more ways than one. The small town has trumped the big city as a site for target practice.

From the individual’s point of view, such an intersection of personal acts and extraneous factors might well appear to be an avoidable eventuality, a gratuitous choice with inevitably tragic consequences. The Pinteresque chill, however, lies in the plot’s near-effortless slide from choice to choice-less-ness, and correspondingly, from closeted normality into a twister of a cataclysm. This is the bit that Basu handles best, the sense that the action had already got off the tarmac, without the Sengupta couple realising its immanence. This is where Basu pitches the shock that he wants his compatriot reader to note in their own responses, the shock of ordinary people comprehending how they have been co-opted, if not bulldozed, into taking sides in a war not of their own making. The resulting sense of violation and betrayal of ordinary citizens’ perception of their place in the democratic system is the central emotion of Basu’s novel. We hear ourselves crying out in chorus, “We certainly count. But do we really matter?”

Yet it is only when we zoom out from the individual’s situated perspective do we see the larger picture, scarier for the very reason that it doubly underlines our powerlessness in the face of history’s dialectics. We should have seen this coming, riding the crest of the very democratic processes that India in its 75th year of Independence seeks to be collectively defined by. Perhaps we are, as Tolstoy argues in his Second Epilogue to War And Peace, but specks in the quantum of historical force? Perhaps our free will is of no consequence at all? Perhaps we should be content to stand by and watch impassively? Basu’s protagonists act otherwise — not just the Senguptas, but Altaf’s mother, Mimi, Veena; and even Devi.

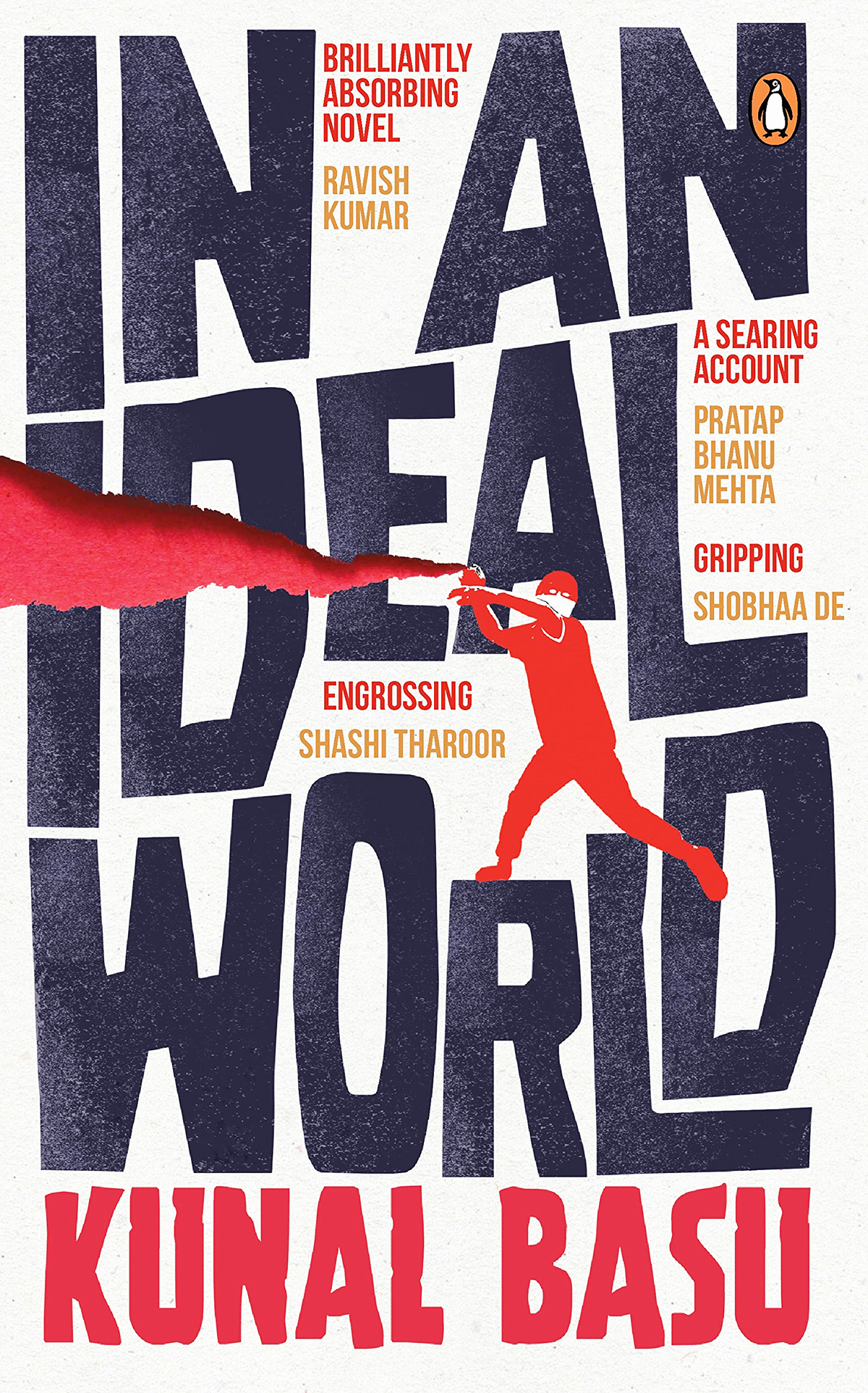

In An Ideal World

By Kunal Basu

Penguin Random House India

pp. 198, Rs 599

Interestingly, much of the resistance to impositions in the story is directly or indirectly steered by some very gritty, spirited women. Nothing can deter Vivek’s asthmatic mother from undertaking the mission to rescue not just her biological son but also truth from dying in encounter. We find this teacher and her banker husband acting progressively not on behalf of their son, but the very coeval and ‘rival’ in whose disappearance their son may have been unfortunately complicit. One is reminded, in this context, of another powerful short story about the spirit of humanity transgressing and hence transcending the walls of biological, social and religious imperatives in times of conflict — Syed Shamsul Haq’s Nishiddha Loban (1990; Forbidden Incense in Saugata Ghosh’s English translation).

The parents find themselves racing against a time bomb, even as the challenge of reclaiming a young mind ambushed and annexed by predatory parasites demands a delicacy that cannot be hurried. The pace of the narrative picks up those signals of initial sluggishness from the protagonists and then, after roughly the half-way mark, turns on them with vicious force. They fail. The author, however, makes it his story’s mission that other parents should not, any more than they should push their young into the fray.

Sadly, the Senguptas are unsuccessful in breaking ice with their son. With his peers, Suraj and Devi, on the other hand, they quickly find the breach through which to open channels of negotiation. In addition to its more pressing focal message, this is one of many insights that this novel lets slip: the vagaries and ironies of human communication. The one who should have understood his parents best, Vivek, proves to me the most wilfully opaque; while strangers whom they had not known at all respond to them in constructive and meaningful ways. In fact, many of Basu’s fictional protagonists, in Racists (2006), Sarojini’s Mother (2020), The Endgame (2020), to name a few, embody the power of the human heart to look beyond ties of blood and property. As family structures alternately crumble and re-consolidate in the global ebb and flow of capital, employment and demography, Basu resiliently holds up examples of human bonding beyond, though not at the expense of the familial.

A true realist makes themselves everybody’s contemporary, younger and older. Perhaps it is this urge to connect with readers across the age and language barrier that prompts Basu to write this story in English; so that the story doesn’t become the story of India. Basu’s fiction is an unflinching reminder to his readers across the English-speaking world that the ‘children of men’ and ‘of war’ are not just ours, or theirs.

Pinaki De’s book cover, black on white, spray-painted with lurid red, is an evocative graffiti of a graffiti. The writing on the wall is hard to miss. The plain irony in the title may well be intended. By contrast, the language of the book is uniformly restrained, even as it must allow some direct declamation and overt sermonising in order to expose, contextually, how deep the fault lines run. Basu’s fiction over the years presents a remarkable blend of reticence and lyricism. In this book, particularly, one senses that the author wanted nothing to distract the reader from the chain of events. There is no ponderous inwardness on offer, which makes one want to designate the book as a novel of action, rather than as novel of ideas.

The only relationship that is allowed space for slow exfoliation in words and silence beyond narrative exigency is that between the Sengupta parents. For the author, it must have seemed the natural thing to do. As they watch old friendships succumb to the expediency of survival, as they wait for their son to come home and wake up to them, all that Joy and Rohini can cling to is the togetherness of an indefinitely elastic present.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated