In 1989, an adolescent schoolboy from downtown Srinagar watched as his elders extricated themselves from university campuses, high-school grounds, handloom machines and farms to bear arms and fight a war of attrition against the Indian state. Twenty-two years on, Jaffna Street was born from his explorations of the human dimension of the conflict appositely termed the Kashmir tragedy.

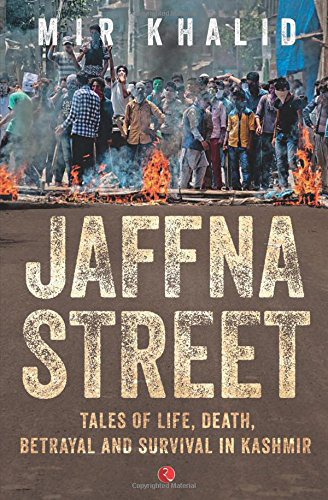

Jaffna Street: Tales of Life, Death,

Betrayal and Survival in Kashmir

By Mir Khalid

Rupa Publications

Rs 295, pp. 304

The impermanence of the existing nation-states and the fluidity of borders abruptly dawned on Zee. In his and others’ reckoning, the moment to pick up arms and widen the contours of a fledgling insurgency, which would set Kashmir free from Indian rule, had arrived. His bid to arrange his arms training in the camps located in Pakistan saw him put in a word of interest to the insurgent underground.

The apprehensive forecasts of being pummeled by the dreaded chillai kalan — the annual cold winter wind that causes Valley temperatures to plummet to sub-zero levels over its forty-day span — failed to deter Zee’s zeal or determination. Unlike most aspiring insurgents, Zee wasn’t banking on intangibles like luck to reinforce his chance of surviving the long and hazardous mid-winter journey across the LoC—the Line of Control. His optimism envisaged tackling it like some child’s play, his smug confidence buoyed by both his athletic zeal and climber proficiency acquired and honed during his student years.

His call came on an exceptionally frosty night in early 1990. Years later Zee vividly recalled the minute details. The insurgent contact spotted Zee immersed in supplication at the local mosque and tapped his shoulder. Zee hurriedly finished his prayers and left the assemblage to rendezvous with the departing group.

1

Perched on the southern embankment of the Jhelum River and abutting the Safa Kadal (Seventh) bridge, the shrine of the medieval mystic-evangelist Niyamat Ullah Shah Qadiri lacks both the imposing grandeur as well as the penitents’ rush of other popular shrines that dot the old quarter of Srinagar city. Its architectural layout carries the hallmark of mankind’s innate Euclidean propensities, blending with the inspiration drawn from Kashmir’s Buddhist past with its centuries-old pagoda spire, sliding roof and single-storey structure. For any imaginative eye, this convergence epitomizes the native Kashmiri society’s subliminal urges, which over the centuries actively sought to acculturate these Iranian mystic-evangelists through the architectural appropriation of their resting places to facilitate their seamless blending into the local urban milieu.

During his lifetime, Niyamat Ullah’s famed clairvoyant faculties burnished his credentials, and afterwards, his predictions acquired mythic dimensions. According to the local folklore, Qadiri’s corpus of prophesies — in the form of Farsi quatrains — was eventually embossed onto copper plates and interred in the mausoleum with his remains in order to prevent prying eyes gaining unwanted insight into the distant future.

One particular quatrain was destined to permanently etch itself into the annals of the Safa Kadal bridge over the span of many centuries. Pertaining specifically to the fate of the Kashmir Vale, this prophecy interestingly posited the Safa Kadal bridge itself in the middle of a promised messianic redemption marked for the Vale in the near distant future. According to legend, the saint’s prescient visions foresaw a vast Muslim Army commanded by a Turkic general, carrying the nom de guerre of Habibullah, emerge from the highlands of Northern Khorasan. This horde would supposedly sweep through the passes of the Karakorum Range and terminate the sufferings of the Vale’s inhabitants at a preordained time in the future. This presaged army would then assemble at the famed Eidgah ground — a furlong or so away from the bridge — and march across the newly rebuilt Safa Kadal bridge to conclude their conquest.

Although allusions to the specific contents of the prophecy attained a pervasive presence over time, interestingly, no written record or material substantiating the quatrain’s existence ever surfaced. Even as the denizens of the Vale chafed under the brutal Sikh rule and later the Dogra monarchy’s depredations, its particulars were distilled, imbibed, garnished and then passed on like a family heirloom, spurring a messianic undercurrent in the Safa Kadal locality. The extent to which the prophecy stirred the imaginations of the inhabitants can be gauged by the fact that the legend of a Turkic warrior-redeemer crossing a river of blood and fire perpetuated itself generations on.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated