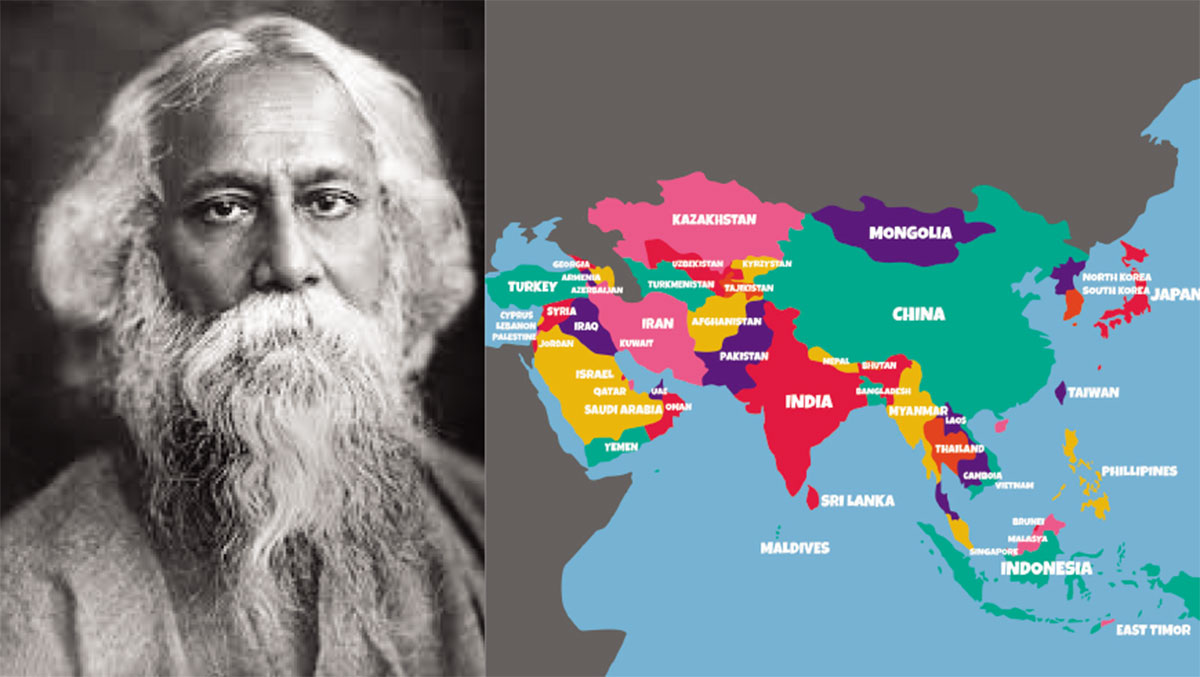

Rabindranath Tagore was the foremost exponent of the word ‘Asian’ and the apostle of the ‘cosmopolitan, humanist, peaceful and spiritual’ Pax Asiana.

Rabindranath Tagore’s assessment that Asia cannot be re-created over ‘a tower of skulls’; his call for Asian solidarity and the need for an Asian mind couldn’t be more relevant now than ever; especially in a world traumatized by the mind-wrecking Covid-19 pandemic, soul-sapping media hysteria, increased threat of corporatized technocratic tyranny and the bizarre economy-killing lockdowns

‘Asia is again waiting for such dreamers to come and carry on the work…of establishing bonds of spiritual leadership’ — Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore, while placing the ‘harmonious philosophy’ of humanism over the ‘great menace’ of nationalism, developed an idealistic concept of ‘Asian civilisation’ and cultivated a spirited ‘Asian identity’.

At the middle of the Bengal Renaissance during the latter half of the 19th century, Keshab Chandra Sen — Hindu philosopher, social reformer and founder of ‘Bharatvarshiya Brahmo Samaj’ — was delivering eloquent speeches about ‘Asian Jesus Christ’, passionately speaking against Europeanizing of Asia and urging India to display an active leadership in the revival, revitalization and rise of Asia.

In such an electric atmosphere, charged further by the emergence of Swami Vivekananda, Tagore’s ‘Asian consciousness’ got influenced in his early days by his ‘Buddhism-inspired’ elder brother Satyendranath; thereafter by two Asians with whom Tagore and his family formed life-long friendships: the Japanese scholar Okakura Kakuzo (introduced by Sister Nivedita) and the Ceylonese Tamil thinker Ananda Coomaraswamy.

Okakura, now more known for the classic The Book of Tea (1906), also wrote powerful and persuasive Pan-Asian works which influenced Tagore: The Ideals of The East (1903) and The Awakening of the East (published posthumously in 1938).

Okakura was an early precursor to the perspectives and insights which are associated with Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961). He argued — at the time of marauding colonization, imperialism, racism and supremacism — that ‘the glory of the West is the humiliation of Asia’.

Okakura emphasized on the need to bring ‘Asian culture’ into the modern realms of global literature and arts while ideating Asia as ‘less a political entity than a metaphysical and spiritual realm’.

The famous opening line of The Ideals of the East — a manifesto for Asian unity that was completed at the Tagore House in Jorasanko, Calcutta, where Okakura spent several months in 1902 — declared emphatically: ‘Asia is one’.

The book received a thrilling response in Calcutta; Tagore later — during his third visit of Japan in 1929 — described Okakura as the ‘voice of the East’ who had completely transformed the way he thought about Asia. Tagore recognized a ‘civilisational struggle’ between the East and the West; he contrasted Asian humanist spiritualism against Western nationalist materialism.

Tagore and Okakura also had key ideological and political differences. But they could transcend them by remaining united through the kindred spirit of Asianism.

The close friendship and the intellectual exchanges between the two Asian thinkers and the people of culture are examined by Rustom Bharucha in Another Asia: Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura Tenshin (2006).

The Tagore House in Jorasanko, Calcutta, became a hub for European intellectuals fascinated by the Orient and for Pan-Asian idealists who were hosted by the family. After Okakura, Ananda Coomaraswamy — an early interpreter of Indian culture to the West — became a regular at the palatial house and made a breakthrough contribution by introducing ancient Indian art into modern theory.

The Messenger of the East

Tagore, the humanist and the Universalist, began to voice his pan-Asian sentiments from the early years of the 20th century. But after becoming the first Asian to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, he began to see himself as the ‘Messenger of the East’; and, thereafter, gave out a clarion call to rediscover the soul of ‘United Asia’ amidst the onslaught of western colonialism, imperialism and cultural dominance.

The idealized Bengali trait of wanderlust or the desire to travel was strong in the Tagore family. But Rabindranath surpassed everyone else, including his own father Debendranath, by travelling to 34 countries.

While travelling and delivering lectures in Japan in 1916, Tagore declared, ‘Only our Asians can understand that the universe has both law and spiritual content. Except for a few poets, the Europeans cannot understand this.’

During Tagore’s visit to China in 1924, Chu chen-tan (the Chinese name for Tagore) extolled ‘the people of China, Japan and India’ to ‘unite together’ to ‘demonstrate to the world our Oriental culture and our special qualities, so that the true value and fame of the Asian peoples will be made known.’

During Tagore’s journey to Indonesia, he was overwhelmed by the beauty of the islands of Java and Bali. He wrote a famous poem ‘To Jawa’ while sitting on the steps of the 9th century Mahayana Buddhist temple of Borobudur.

In the same year, 1927, Tagore visited and delivered lectures in Siam (Thailand), Malaysia and Singapore. In 1929, he visited Vietnam.

In Iran — during Tagore’s travels in West Asia in 1932 — Tagore was viewed as a prophet and a spokesman of ‘Asia’s great dreams’. The reception held for Tagore at the shrine of the Persian poet Sheikh Sa’di got such an overwhelming response that the army had to be brought in to control the crowd. Tagore read from a book of Hafez’s poetry while sitting near his tomb in Shiraz. He also held a symposium on the ‘Unity of Asia’ and hoped for ‘United Asia holding out her hands to the West in friendly manner.’

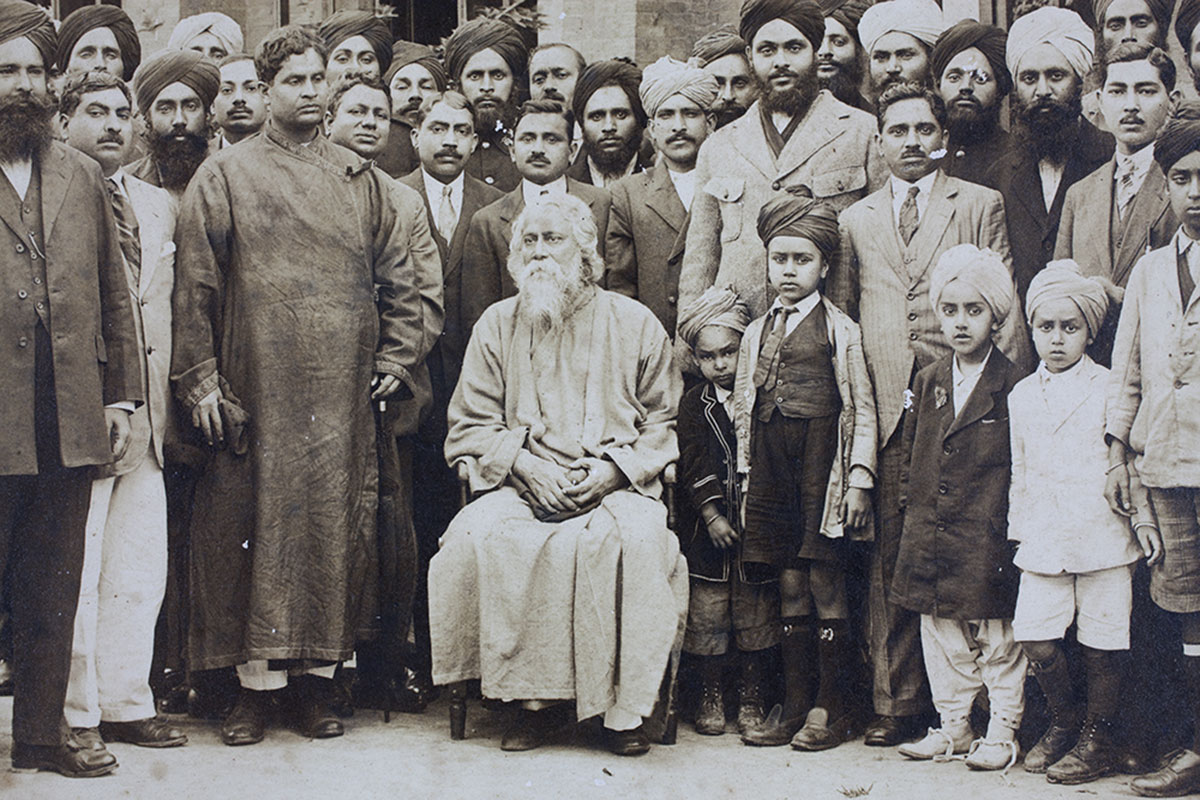

Rabindranath Tagore on a visit to Shanghai, China, in the 1920s. Photo: Ranjit Singh Sangha

Tagore travelled and lectured extensively with the sense of being an ‘Asian’ that implied to him, to be a naturally born ‘humanist’. While focusing upon the renewal of the ideals of ‘Asian humanism’, ‘Asian civilization’ and ‘Asian identity’, Tagore wanted to revive the deep-rooted cultural links between different regions of Asia which have woven intricate civilizational patterns throughout history since time immemorial.

Inspired by such sentiments, Tagore founded Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, Bengal, in 1921, which continues to attract students from various Asian countries. Kala Bhavan still enjoys an anointed position as one of the best departments for fine arts in India.

Visva-Bharati’s given motto is ‘where the world makes a home in a single nest’, but in practice, it is more like ‘where Asia makes a home in a single nest’.

Tagore — in his quest to ‘create an Asian mind’ — turned Visva-Bharati into an Asian cultural abode where students could take courses in Chinese literature, Persian, Japanese, Indonesian Batik printing, old Persian, Indo-Iranian philology, Zoroastrianism, Islamic history and more.

Tagore was prescient about the significance of China in the context of Asia and the world. Tagore roped in Chinese scholar Tan Yun-Shan to establish ‘Cheena Bhavana’: a dedicated centre for Sino-Indian cultural studies — along with a dedicated library — at Visva-Bharati in 1937.

Cheena Bhavana is the oldest centre for Chinese Studies in the subcontinent. During its inauguration — described by Tagore as ‘a great day for me’ — he emphasized that the people of India and China need to keep ‘an ancient pledge to maintain the intercourse of culture and friendship … whose foundations were laid eighteen hundred years back by our ancestors with infinite patience and sacrifice.’

Where Have We Come Since Then

Tagore died in 1941. His dream of a ‘United Asia’ is largely unrealized due to the swirling currents of history which have flowed since then. Asia has witnessed fragmentation as well as integration: while certain fissures and fault-lines have healed, many others have worsened.

What transpired in the last eight decades would have exalted, as well as horrified, Tagore. Being a life-long anti-imperialist, he would have welcomed the retreat of the old Empire’s colonial shadow over Asia, while actively opposing the wars, invasions, interferences, exploitations, impositions and encroachments by the new Empire. West Asia would have perennially depressed him with the incendiary cauldron of Sunni versus Shia, Wahhabi versus Muslim Brotherhood, Israel versus Palestine and the ‘Empire’s proxies’ versus the ‘Axis of Resistance’. He would have viewed Russia’s re-emergence from the wreckage of Communism and her current ‘Sovereign Eurasia’ mission in new light; his interview in 1930 during his visit to the Soviet Union where he had made a critical assessment of the Communist system was barred from publication on the orders from Joseph Stalin, but it was eventually published by the same daily Izvestia in 1988 under Mikhail Gorbachev. The integration of ten South-East Asian countries as ASEAN would have given Tagore hope. He would have viewed the tragic Sino-Indo conflicts as fratricide; he would have asserted that Asia cannot regain her rightful place in the world by creating — what he once called in the context of Sino-Japanese tensions — ‘a tower of skulls’.

More importantly, in the year 2020, Tagore would have been extremely eager to see what happened to India’s nurturing of the identity of being an ‘Asian nation’ and the Indian citizens’ conception of being an ‘Asian’.

The ‘Asian Identity’ of Indians

One doesn’t expect a marginalized impoverished Dalit or an indebted farmer in the hinterlands, already burdened by the predatory politics of identity — of caste, religion, gender, language and community — to even know about the word ‘Asia’. But what about the educated, the urbane and the cultural elites: Have they developed an ‘Asian mind’ or an ‘Asian identity’?

I decided to conduct a random amateur survey via WhatsApp by requesting people — of various age groups — from my largely Anglophone social circle to answer four questions which will reveal whether they think themselves to be Asians or not, and to what extent.

The results of the survey were encouraging, distressing, complicated and fractured.

Encouraging: because everyone had travelled or wished to travel to one or more Asian countries and have been exposed to some facet of Asian culture — other than of India — be it a movie such as Parasite or a book such as The Art of War or a type of music such as K-pop or a TV series such as Ertugrul. And a sizeable majority had an innate interest in certain aspects of Asia: be it a specific art form or a cuisine or a particular nation or a slice of history, such as the journey of Xuanzang to India or the story of Angkor Wat in Cambodia.

Distressing: because there were shades of Islamophobia and Sinophobia, along with the propensity to discriminate on the basis of physical appearances and religion: the two factors which the politics of Hindutva nationalism exploit to engage in constant ‘othering’ of different religions and fellow Asians — like those from East and Central Asia — as menacing invasive elements from the ‘outside’: an existential threat to everything that is ‘Hindu’.

Unfortunately this well-propagandized narrative — however regressive it might be — has seeped into the minds of many, even within those who don’t see themselves as right wing conservatives, but identify themselves to be centrists, or liberals.

Rabindranath Tagore at Tomitaro Hara’s Sankeien in Yokohama, Japan. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Complicated and fractured: because some didn’t think to be as Asians at all; some thought themselves as ‘South Asians’ or belonging to the ‘Indian sub-continent’; some thought themselves to be ‘geographically Asians’ but ‘culturally more conjoined’ to America or England; and only a few thought themselves to be ‘true-blooded Asians’ and felt ‘a profound connection’ to the syncretic history and the prodigious diversity of people, culture and landscape of the vast continent.

The overall conclusion would have disheartened Tagore; the majority of those who completed the survey didn’t possess an ‘Asian identity’ in the manner of his interpretation that emphasized upon Asia’s humanism, social organization, wisdom cannon and spiritual consciousness.

Asia itself is seldom perceived as a ‘whole’ in the present circumstances, but rather seen and understood as different regions: West Asia or the ‘Middle East’, Central Asia, East Asia, Far East Asia, South Asia, South East Asia and Eurasia (perceived in two ways: when one includes Northern Asia or Russia, or when one includes Europe with Asia to suggest a ‘supercontinent’).

The survey findings get ratified further by our current Anglo-American-centric ‘socio-cultural eco-system’ that is more westward gazing, than being remotely pro-Asian.

To cite an example, Indian historian and public intellectual Ramachandra Guha wrote a recent essay ‘No, China will not conquer the World’ where he argued that China won’t succeed Britain or America as the most influential nation on earth because Chinese culture is not ‘remotely as appealing outside China as British culture once had been outside Britain and American culture still is outside the United States.’

There are several points to contest in the essay tilted towards the Occident, especially Guha’s implied assumption that a hegemonic empire can only be succeeded by another hegemonic empire, while in reality, within the next decade or two, the Asian Century will be truly well-established along with a Multipolar World Order — diversification of global political, economic, technological and cultural power — rather than the continuation of the fraying Unipolar paradigm.

But what struck me most was Guha’s assertion that in terms of cultural offerings or soft power, ‘all the Chinese have to offer the world is their cuisine’. And then he goes on to mention Shakespeare, Dickens, Hemingway, Faulkner, Clint Eastwood, Meryl Streep and more as instruments of western ‘cultural hegemony’ while he couldn’t even mention Lao Tzu, Confucius, Sun Tzu, Li Bai or Li Po, Xuanzang, Cao Xueqin, Bruce Lee, Gao Xingjian, Wong Kar-wai, Yue Minjun, Zhang Xiaogang, Zhang Ziyi, Jackie Chan, Ai Weiwei, Fan Bingbing, Liu Cixin and more. Not a single name of a globally influential Chinese philosopher, writer, poet, traveller, artist, film director and actor; just ‘Chinese cuisine’!

Tagore — the architect of Cheena Bhavana — would have been stunned at the ignorance of the current Indian Anglophone cultural elites who still allow themselves the ignominy — as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak would say — to be ‘intellectually colonized’ by the West, and continue to gather their worldview exclusively through the Empire-filtered lens of Western mainstream media and culture.

More so when Tagore had opposed and rejected the colonial ‘Memorandum on (Indian) Education’ formulated by Thomas Macaulay that intended to produce ‘a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, opinions, in morals and in intellect.’

Tagore’s view was: ‘Some of us, of the East, think that we should ever imitate the West. I do not believe in it. For imitation belongs to the dead mould; life never imitates, it assimilates. What the West has produced is for the West, being native to it. But we of the East cannot borrow the Western mind nor the Western temperament.’

But in the 21st century India, the ideas, phrases, perspectives, theories and narratives of the mainstream Anglophone West — mostly UK and USA — continue to be overemphasized, overestimated and overvalued. They are often ‘worshipfully regurgitated’ by the Indian mainstream that display a deeply ingrained reticence — or a ‘compulsive mental block’ — to reassess, verify, critically examine and challenge them by including perspectives from other, alternative, indigenous, independent or progressive sources.

This widespread societal phenomenon — stemming from the socio-cultural conditioning and the psychological effects of two hundred years of servitude — remains an anachronistic, submissive, counter-productive, inferiority-complex-ridden and pestiferous trait — or rather, a pathological disorder — of present India.

When a large chunk of the Anglophone Indians — representing all the major sections of the political spectrum: the right wing, the centrist liberal and the left — remain grievously handicapped by their dismal failure to diversify and broaden the sources of global news, expert analysis, academic work and cultural influences, Tagore would have concluded with grave anguish that far from developing an ‘Asian mind’, India — still intellectually immature — is yet to emerge fully from the penumbra of the Empire.

Tagore and the Asian Century

Tagore — the foremost exponent of the word ‘Asian’ and the apostle of the ‘cosmopolitan, humanist, peaceful and spiritual’ Pax Asiana — was also much ahead of his times. He was often misunderstood; especially during his lectures in Japan and China where the people didn’t always warm up to his Asia-centric philosophical messages which also eviscerated and censured the two popular ‘isms’: nationalism and materialism.

But by the mid-1980s — more than four decades after Tagore’s death — Asia finally became a major talking point in the global corridors of power. And, in 1988, during a meeting with the Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in Beijing, the leader of People’s Republic of China Deng Xiaoping referred to the next ‘century of Asia and Pacific’. And since then, the momentous neologism ‘Asian Century’ entered the zeitgeist of our present era.

The term has now grown in popularity; countless books centered upon the theme of the ‘Asian Century’ are being churned out in the recent years from The New Asian Hemisphere: The Irresistible Shift of Global Power to the East (2008, Kishore Mahbubani) to The Future is Asian: Global Order in the Twenty-first Century (2019, Parag Khanna).

But let us always honor and remember that the genesis of the modern conception of the Asian Century began from the heart of the Bengal Renaissance that also sought Asia’s rise during colonial India, especially from the Tagore House in Calcutta, when a visiting Japanese scholar ideated ‘Asia is one’. This, in turn, nourished Tagore’s Asianism, prompting him to travel widely as the prominent proselytizer of Asia’s revival, revitalization and reemergence, based upon the civilizational values of the East.

Tagore once told a group of Chinese students, ‘It would be degradation on our part, and an insult to our ancestors, if we forget our own moral wealth of wisdom, which is of far greater value than a system that produces endless materials and a physical power that is always on the warpath.’

From Tagore we learn that instead of the imperialist ‘Western Way” of development based upon nationalism-driven militarized conquests and coarse materialism, the path of Asia’s rise should follow the non-imperialist ‘Eastern Way’ of development based upon humanism-driven cooperative solidarity and sublime spiritualism.

*

The inexorable process of the Asian Century has already begun. The tide of history and the forces of time have turned towards the East. In such a situation, to recall Pablo Neruda, ‘You can cut all the flowers, but you cannot stop spring from coming.’

Even in this unprecedented year of 2020, the ‘pandemic has clearly shown the world’ — to quote Amitav Ghosh — ‘that Western countries are no longer exemplars of good governance, or of best practices.’ Kishore Mahbubani wrote in The Economist: ‘The West’s incompetent response to the pandemic will hasten the power shift to the east.’

In such a pivotal era-shifting moment, it doesn’t suit India’s overall interest to be the Empire’s hostile counter-weight to China. Instead of fostering peace, resolving conflicts and directing precious resources to cover the massive deficiency in capital expenditure, poverty alleviation, development and welfare, India could be prompted to exert pressure on various strategic nodes to disrupt the New Silk Road (The Belt and Road Initiative), get hopelessly mired in a web of blowbacks, overspend on military procurements which will only benefit foreign suppliers, and even ratchet up border tensions — for the sake of saber-rattling jingoism of Hindutva nationalism and to emotionally rile up and manipulate voters before elections — that might inadvertently escalate, and even risk a real war — with Pakistan or China, or both — that would certainly burn the Asian Century — and herself — in the process.

This ominous possibility — that would be like committing hara kiri in terms of peace, development, geopolitics and finance — will keep hanging over the nation like a guillotine, as long India is ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and especially, by the current Modi regime.

Rabindranath Tagore at the Majlis (Iranian parliament) in Tehran, Iran, 1932. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The historical genesis of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Hindu Mahasabha — that has led to the BJP and the right wing sphere of Indian politics — has been influenced by European nationalism, fascism and Nazism. The Hindutva ideological sphere and Narendra Modi also closely collaborates with Zionist Likud Party of Israel, a country that Modi visited as the first Indian Prime Minister in 2017, as well as the first Chief Minister of an Indian State in 2006.

The Vivekananda International Foundation — the most influential right wing think tank that is closely associated with the RSS, the BJP and the Indian Government’s NITI Aayog — also ‘brainstorms’ and collaborates with the US think tanks: the Atlantic Council and the Heritage Foundation.

All such deep-rooted connections of the Indian right wing with US and Israel have resulted in the complete tilt — or rather surrender — of India’s current foreign policy and socio-economic management to the axis of the Empire, with disastrous consequences, with no sign of any course correction.

India no longer has a completely sovereign worldview and an independent spectrum of policies; she is being run through the eyes and mind of the Empire, and has become a Petri dish of neoliberalism on steroids.

Even the Indian mainstream media — that has largely become the lapdog of the current regime — has also tilted completely towards the Empire.

An overwhelming majority of ‘factory-produced’ news reports, opinion pieces and boisterous TV discussions always repeatedly use the Empire-sanctioned phrases like ‘Chinese aggression’, ‘Chinese attack’ and ‘Chinese expansionism’ which are meant to sow discord, maintain antagonism and rule out the possibility of any détente between the two sister civilizations of Asia.

India — its ruling regime, a large faction of the mainstream media and a bevy of biased experts — is working to facilitate the Empire’s vision of ‘disjointed and unharmonious’ Asia, rather than to inspire India to work for the cause of the rising Asian Century, by joining the New Silk Road (BRI) and solving conflicts for the sake of a hopeful new era, instead of festering them, to prolong the tension-soaked status-quo, that only favours the declining Empire.

Tagore would have judged all such developments extremely sternly as an abject betrayal of India’s ‘anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, non-aligned history’ and perhaps, also as a terrible stab, at the back of Asia.

Those who still take soulful inspiration from India’s glorious struggle for Independence will find it abominable to ever see, India — instead of firmly offering her hand of friendship as an equal sovereign partner — is once again timidly saluting, another Western Master.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated