Thomas Mann

Snatches from a conversation with Thomas Mann and Jawaharlal Nehru at Cambridge, 1952: “Every writer carries on his shoulder the burden of understanding. He looks around comprehending the world with all its complexities and contradictions”

Midway through the Michaelmas term of 1952, Cambridge went agog with excitement over the announcement that the university would honour some celebrities from all over the world with honorary doctorates. Amongst these luminaries were Thomas Mann, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sir Thomas Beecham, and General Smuts.

I decided not to get anywhere near General Smuts or Sir Thomas Beecham because while the former was a British citizen being honoured by his own country, the General to me always seemed to be a military adventurer. I never cared to attend any concert given by Beecham because he couldn’t hold a candle to Toscanini who was a musical wizard. Let me say that in spite of my financial constraints, I had travelled twice to London to attend Toscanini’s presentation of Beethoven at Royal Albert Hall. I remember that cold winter evening, with a line of his admirers waiting to buy their tickets. Surprisingly, the great musician himself appeared on the scene to tell them how much he appreciated their love and admiration for him.

So the only two luminaries I wanted to meet were Thomas Mann and Jawaharlal Nehru. Even between these two, I was more eager to have a word with the great German Nobel Laureate rather than conversing with the Indian Prime Minister whom I had heard several times on Ramlila grounds in Delhi. This special convocation, I thought, would give me a unique opportunity to meet Thomas Mann the writer of my dreams — a writer whom I always looked upon as the novelist’s novelist.

This convocation was to take place in the Senate Hall which stands right in the middle of Cambridge, next to King’s College. Since the seats were limited, I used my position as President of the Cambridge Majlis, and a compatriot of Nehru, to secure a seat in the hall. It turned out to be a very impressive ceremony with the citations read both in English and Latin. I almost turned off my mind when Sir Thomas Beecham and General Smuts were introduced to the audience. Of course, I listened attentively when the Rector introduced Jawaharlal Nehru as one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century, besides being an alumnus of Cambridge. I could see that the audience was impressed by the Indian Prime Minister, handsome like a prince who had been educated at Harrow and Trinity. But I was all concentration when Thomas Mann was presented to the gathering as a creative writer with a unique vision.

Ceremony over, I followed Thomas Mann out of the hall, but Nehru was already holding his left arm, leading him to the annexe behind the Senate Hall. Determined to get Mann alone, if possible, I followed them both. But before I could catch Mann’s attention, Jawaharlal Nehru turned around to see a brown young man with his eyes glued on the novelist.

Pandit Nehru asked me, “Are you from India, young man?”

“Yes, Sir,” I replied, still looking sideways at Mann.

“Are you here for your Tripos or research?”

“I’m doing research in English Literature.”

“What college are you attached to?” Nehru enquired.

“Fitzwilliam House, Sir.”

“Ah, so you are a Fitzbilli,” Nehru quipped.

I knew that at Cambridge anyone enrolled at Fitzwilliam was nicknamed Fitzbilli, derogatively. Fitzwilliam House took in students, mostly from overseas who could neither get admission elsewhere nor afford to have rooms at Trinity, St. John’s, Corpus Christi or Peterhouse. But since Fitzwilliam House stood facing the great FitzWilliam Museum across the street, we often misled tourists from Europe or elsewhere that the museum was a part of our college.

Nehru then remarked, “I wonder if you know that I was at Trinity where I did my Tripos in Natural Sciences.”

“Yes, Sir, I know all this from your Autobiography. I feel proud to see you here, my Prime Minister.” Nehru crimsoned at my compliment.

Then after a brief pause, he asked, “How is the Majlis doing these days? I wonder if you know that I was vice-president of this organisation during my stay here.”

“Yes sir, I know that too. Incidentally, I am presently the president of the Majlis.”

“Oh! I am pleased to hear that.”

I told myself not to spend any more time speaking to someone whom I had heard at several public meetings in India. So, I now turned to Thomas Mann who had listened to my conversation with Jawaharlal Nehru.

“I claim to be one of your great admirers Dr. Mann. Permit me, to tell you that I have read almost everything you have written — novels, short stories and even the book The Making of a Novel”.

Smiling he said, “I am delighted to meet you and thank you for sparing time to read my work when you should be occupied with your own research. Anyway, may I ask you which of my novels you liked most?”

“The Magic Mountain, one of the great classics of our time.” I responded.

“Why has this novel appealed to you particularly?”

“For its authentic emotion. The scene that has remained in my memory is where you describe Hans Castorp’s return from the sanatorium to his own family. At the dining table, his father says, “Hans, why don’t you have another helping of tomato juice? It should be good for you.” Hans is put off because he realizes that even his family has not accepted him as a normal healthy person, entirely cured of tuberculosis. He wanted to return home totally rejuvenated, oblivious of the ailment that had kept him captive at the sanatorium.”

As I finished, Mann darted a close look at me and said, “A very sensitive observation of the scene. Let me share a secret with you, young man, that the scene is based on my personal experience. I had spent a couple of years at a sanatorium in Switzerland, and I faced the same discomfiture when my father advised me to take another helping of tomato juice. So, you see, there is an autobiographical element in this novel.”

“This leads me sir, to ask you — Isn’t most writing autobiographical?”

“Not really, because creative imagination has its own mysterious ways of making up characters and situations which have no relationship to real life. When a writer uses a part of his personal experience, his pen takes over and races away on the page so that the writer himself may marvel at what he has written.”

At this point Jawaharlal Nehru intervened saying The Magic Mountain is a great novel indeed, I would like to pay my own tribute as well.”

Then Mann asked Nehru, “Aren't you a writer to? May I ask you how much of your personal life has gone into your book Glimpses of World History? Let me tell you that I have enjoyed reading your Autobiography. The point I want to make is that autobiography and other kinds of writing may often cross into each other’s domain. I was probably autobiographical when I wrote my book, The Making of a Novel.

There was now a long pause as three pairs of eyes focused on each other’s face. Then I remarked, “But the greatest piece of writing you have done, in my opinion is your short story “Tonio Kruger”. I wonder if there could be a greater marvel of creative writing.”

Promptly, I pulled out of my handbag a copy of his short stories, turned over to a particular page and requested Thomas Mann to autograph a paragraph that I pointed out to him. He looked at the French quote in the paragraph and glanced appreciatively at me.

“You certainly understand me better than most readers. You know when I inserted that French quote, “Tout comprendre c'est tout pardoner”, it was to share the thought with my readers that if one understands another individual’s failings one should also offer him forgiveness. You see, every writer carries on his shoulder the burden of understanding. He looks around comprehending the world with all its complexities and contradictions. But finally, he should not apportion blame to anyone. You may have noticed in this short story that I envy happily married couples walking along the pavements. Such happiness has never been my lot. It seldom comes to any writer because creation emerges from pain, like a mother giving birth to a child after agonizing labor pains.”

I was blown over by his insightful observation about the creative process. For a few moments, I just kept looking at him, dumbfounded.

“Sir, this brief conversation with you will remain with me forever.”

“I imagine that you would also like to be a writer, spinning out novels and short stories.”

“Poetry too, Sir, for it’s my first love. It’s my dream to become a writer, and I will always look upon you as my mentor”. I paused. “Of course, I know I have to first get to the end of my research project. However, allow me to say that having gone midway through my research, I realise that all research is playing games with ideas. But I need a label, Sir, to carry home to my father who has sent me here in spite of being financially handicapped. A doctorate from Cambridge will work like a talisman to help me get a job in my country. Once I get a job at any university, where do I go from there? My ultimate dream is to become a writer and this is where I need your blessings.”

“Indeed you will blossom into a writer and you will always carry my good wishes.”

In order to divert my attention, Pandit Nehru intervened. “How is the Majlis doing?”

“Pretty well,” I answered. Then added, smiling, “I hope it will do better still, now that I have taken over as its President.”

At this point Nehru intervenrd, “You have had enough of Mann. Now let me take him away because I have also things to talk to him.”

I understood that Nehru’s ego had been hurt because he felt that a young Indian had almost ignored his own Prime Minister. I recalled how John Gunther in his book Inside Asia had disclosed that Nehru had written an article on himself, anonymously, titled “Darling of the masses”. How could he allow a young Indian to monopolize another person in his presence?

I just walked away smiling, feeling pleased that I had met two celebrities at Cambridge.

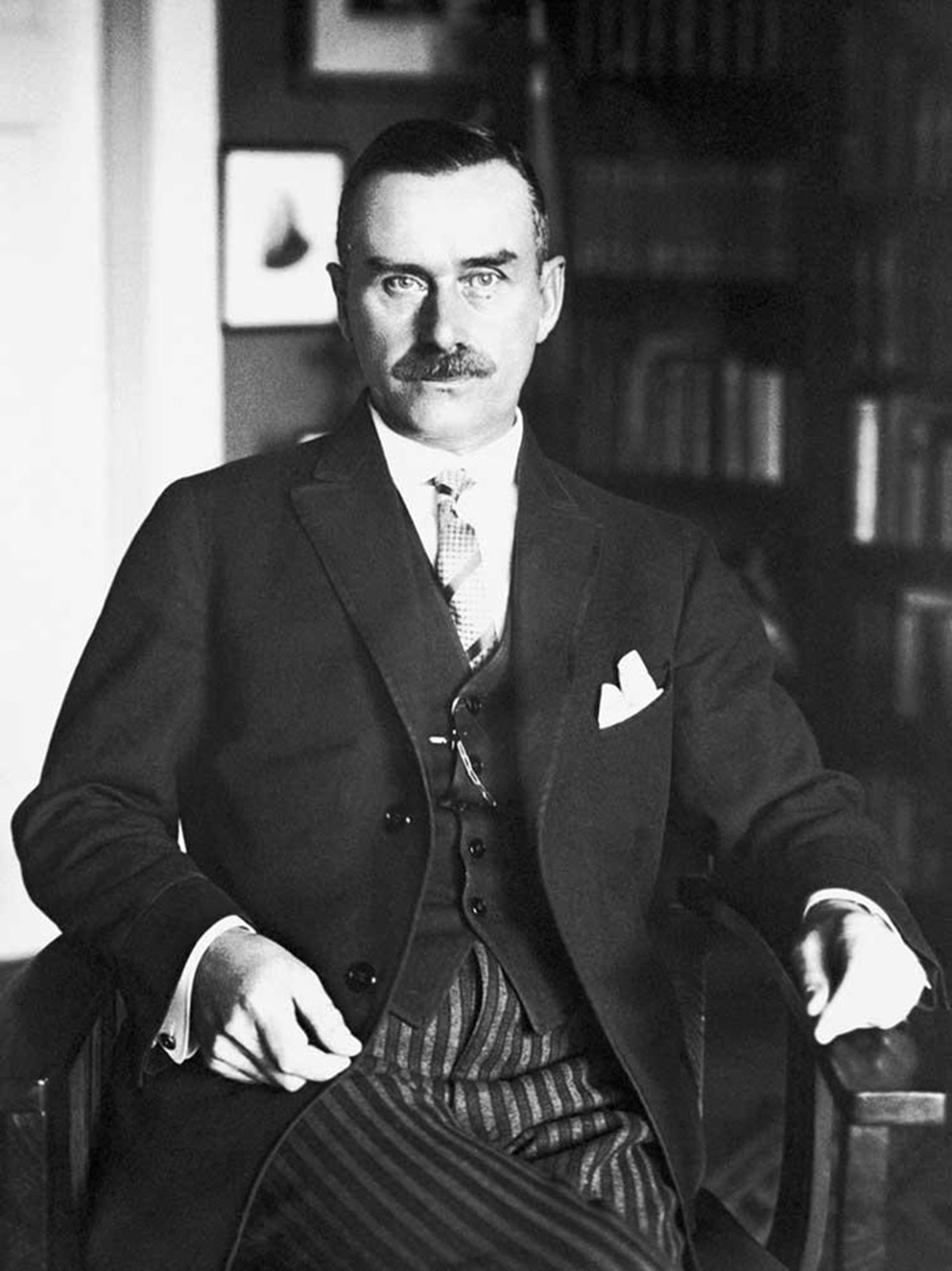

Bio-sketch

Thomas Mann was born on June 6, 1875 at Lubeck, Germany. He attended the science division of a Lubeck Gymnasium and later graduated from Ludwig Maximillians University of Munich. Later he took up journalism as his career and also studied history, economics, art history and literature at the Technical University of Munichand. He emerged as a literary figure when he started writing for Simplicissimus. Mann’s first short story, “Little Mr Friedemann” was published in 1898. But it was a story “Tonio Kruger” brought him into limelight as a highly sensitive and imaginative writer which was also turned into a film.

When Hitler appeared in Germany as a fascist leader, Thomas Mann migrated to Switzerland from where he went to the USA. In 1929 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his literary eminence. He was also honoured by the University of Cambridge with a Doctorate of Letters in 1952, together with Jawaharlal Nehru who was awarded a Doctorate in Law.

Some of his noteworthy publications may be listed as under:

• Buddenbrooks (1901)

• Tristan (l 903)

• Tonio Kruger (1903)

• Royal Highness ( 1909)

• Death in Venice! (1912)

• The Magic Mountain ( 1924)

• Mario and the Magician (1929)

• Joseph and His Brothers, tetralogy

• The Tales of Jacob (1933)

• The Young Joseph (1934)

• Joseph in Egypt ( 1934)

• Joseph the Provider (1943)

• Doctor Faustus ( 1947)

• The Holy Sinner (1951)

• The Black Swan (1954)

He died of atherosclerosis in a hospital in Zurich in 1955, and was buried in Kilchberg.

Jawaharlal Nehru, son of Motilal Nehru, was born on November 14, 1889 at Allahabad. He was born in an aristocratic family. His father was a famous lawyer. With successful early education at home Jawaharlal was sent to Harrow, one the best public school in England. From there he went to Cambridge, and did his Tripos in Natural Sciences at Trinity College of the Cambridge University. After his return to England he plunged into National politics and became one of the most leading leaders in India’s national struggle for freedom. He was arrested several times and spent some years in prison at Nainital where he wrote his famous book Glimpses of World History. He also authored Discovery of India and his autobiography gives an insight into his life and achievements.

In 1947, when India attained Independence, he became its first Prime Minister. But he was known more as a visionary that a pragmatic politician. After his death, his daughter Indira Gandhi succeeded him as Prime Minister of India.

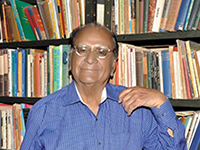

Editor's Note: Professor Shiv K. Kumar (August 16, 1921, Lahore, British India-March 1, 2017, Hyderabad, India) was an Indian English poet, playwright, novelist, and short story writer. This piece has been excerpted from the book he was working on during his last days, Conversations with Celebrities. While the book could not see the light of the day, Professor Kumar, literary director of The Byword, the earlier avatar of The Punch Magazine, was generous enough to allow us to carry excerpts from his unpublished book.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated