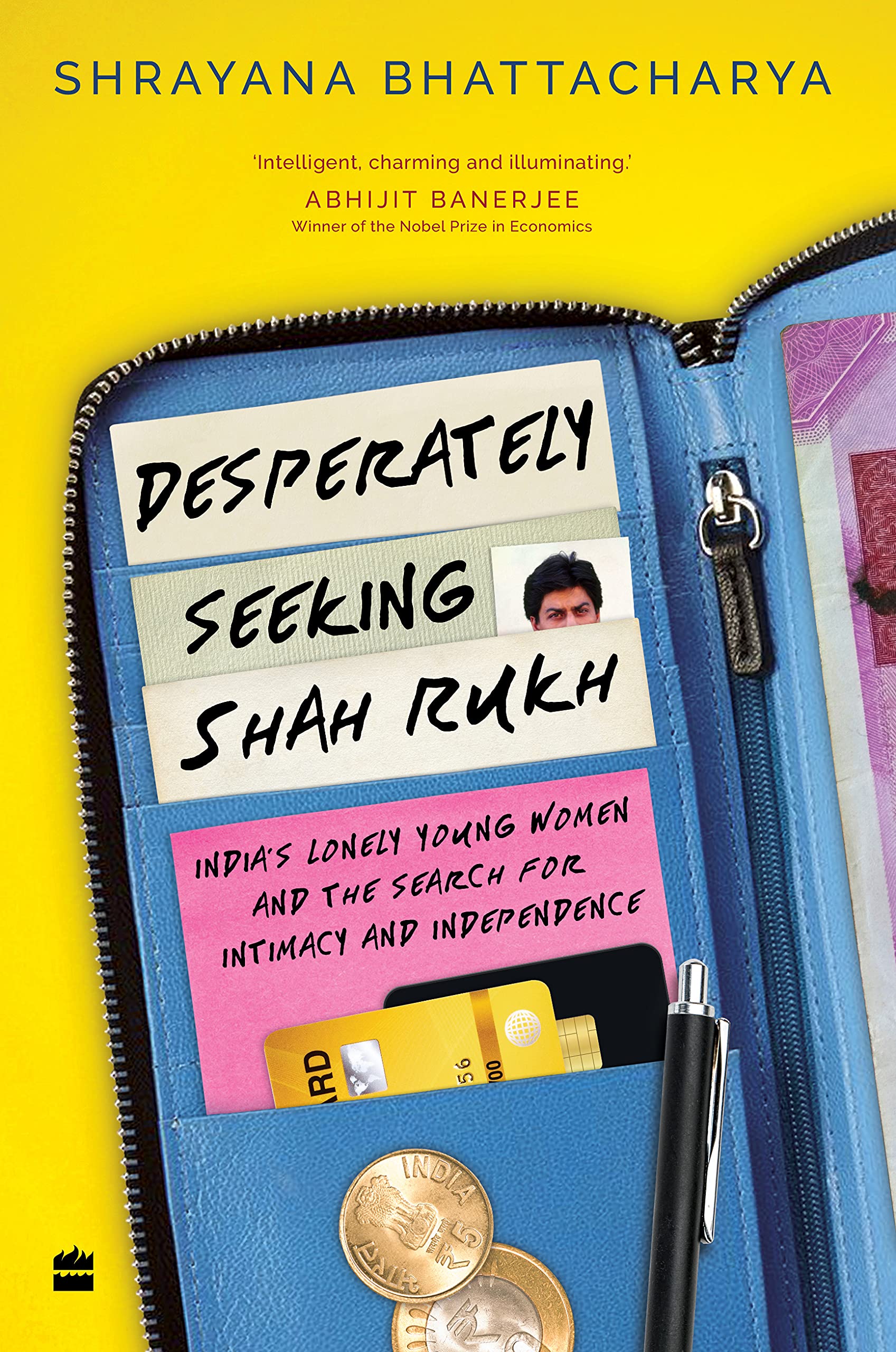

Shrayana Bhattacharya, author of Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India's Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence. Photo: Sukruti Anah Staneley

I spent more than a decade talking to a diverse cohort of women about a movie-star: Shah Rukh Khan. I had made friends with them through seemingly silly conversations about fandom and films. It freed me from having to look at the lives of women through the prism of deprivation and poverty alone. It helped me see the field better.

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

(‘The Field’ by Mark Strand)

It feels awkward to write a personal essay after completing a cycle of book promotions. Since November 2021, I fear that all attempts at writing, thinking and speaking often degenerate into a self-absorbed parade of my vanity. Adding to this palpable sense of awkwardness, I am acutely aware that I do not really live a particularly inspiring or instructive life, nor one of any aspirational value. My daily routines and personal journey are typical of any elite English-speaking woman bearing upper-caste privileges in India. Like many of us, my current struggles involve holding on to a stable sense of selfhood and routine following the losses and spiritual lethargy triggered by multiple waves of the pandemic. Like any woman in one of the world’s most insidious patriarchies, I valiantly struggle to make peace with the scripts of femininity, beauty and duty. My life is rather dull with its banality.

Of course, remarkable stories lie in seemingly banal spaces. I spent more than a decade talking to a diverse cohort of women about a movie-star. His images were ubiquitous in mass culture; his popularity was a bygone conclusion. However, each woman I met experienced his imagery uniquely. While Bollywood may seem frivolous and common to the high-minded, through these conversations, I realised how the banal popularity of a Hindi filmstar created an unusual set of shared metaphors, concepts and idioms across deeply different classes and communities. Popular cinema allowed so many women to openly discuss their beliefs, experiences and philosophies. All talk of a matinee idol freed me from treating the women I met as “respondents.”

Often, the tools and techniques of social science survey research — particularly the variant deployed in development and policymaking — tends to socialise students into entering the lives of others through the narrow prism of a “research question.” Through a series of accidents, I was forced to confront and abandon the mental models of the Survey.

In 2006, I was in my early twenties, and a devoted member of the ‘Survey-Wali Didi’ tribe. After completing my masters, I was earnest, eager and gifted at glibly using data to hide my smug saviour complex. All the while, I anticipated and dreaded disillusionment. Like many students of development, I was academically groomed to be a firm believer in the cult of the Survey. I could not wait to find the ‘field,’ to produce ‘rigorous research’ which would urge ‘policy-makers’ to reassess the effectiveness of various government interventions. I was possessed by words such as ‘patriarchy’ and ‘agency.’ Having studied gender and development, I found a pulpit for my inner zealot at a feminist think-tank conducting action-research into the lives of women working in ad-hoc and poorly paid jobs.

Upon reaching the first site for our research in Ahmedabad, my enthusiasm met the ennui and eye-rolls of the women I was supposed to interview. These communities of women workers had been actively unionizing and fighting for their labour rights. They were thoroughly disinterested in answering my standard questions on wages and working conditions. Some of the women told me they had been surveyed many times by multiple research agencies before and were tired of the same old questions. Workers did not need a survey by outsiders for advocacy; they were fighting for their own rights every day. Some women had conducted their own survey on wages and hours of work, presenting these findings to government officials and partner NGOs. Their evidence collection had not yielded much action on tightening regulations and improving their earnings. One such woman said, “You ask these questions and think it is useful. It really is not. Why do you ask questions when we all already know the answers will not help.” These utterances were never made with any acrimony, but with bemused boredom.

To ease conversation and to help us go through the motions of our survey questionnaire, we decided to take a recess from the formal research and started talking about our favourite film stars. Suddenly, many women started giggling, the tone and texture of the conversations opened up. I noticed this shift in energy from Ahmedabad to UP, to various other places I was sent to do “fieldwork.” I did not know it back then, but this accidental atmosphere of joy and fun triggered by the mention of an actor would introduce me to a set of women I would follow for most of my adult life.

Fifteen years since I unknowingly began the research that culminated in my recent book, for the women I’ve followed and chronicled, the ability to watch a movie star was an easier way for women to discuss their difficulties in gaining financial independence. In telling me about why they loved his imagery, they told me about how he had become a spiritual timeout from the alienation, rational trade-offs and determinism of modern life. His songs and scenes provided respite when the world did not feel human, when these women felt disposable. When families and workplaces refused to treat women as people with desires and rights. When love became a chore. A break when practising accountability in intimate interactions felt lonesome. When the moral burden of propelling social change within their immediate relationships became too taxing or lonely-making.

That rupture in 2006, when my foolish twenty-something self was forced to abandon the mental model of a survey, changed the way I understand the field of research. Leaning into the idea of a movie-star as a research tool to understand women’s lives better helped collapse the divide between the ‘field’ and myself. I realised that my own life was as much a field of study as the poor neighbourhoods I was surveying. This insight pushed me to talk to women from my own milieu about our favourite filmstar. My local café and bars became the field. Delhi’s drawing rooms became the field. I studied myself and my dear ones, as much as I studied strangers. The street outside a film-star’s home became the field.

I made friends through seemingly silly conversations about fandom and films. In a country as divided as India, I am grateful that silliness and fun allowed us a window into each other’s lives, and that an actor offered us a topic of mutual learning and interest. Obliged that all talk of a film icon liberated me from a researcher’s extractive gaze of ‘data collection’, that his films and songs freed me from having to look at the lives of women through the prism of deprivation and poverty alone. I may have no robust answers or theories, but I’ve learned to ask better questions. I see the field better, and my own role in it.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated