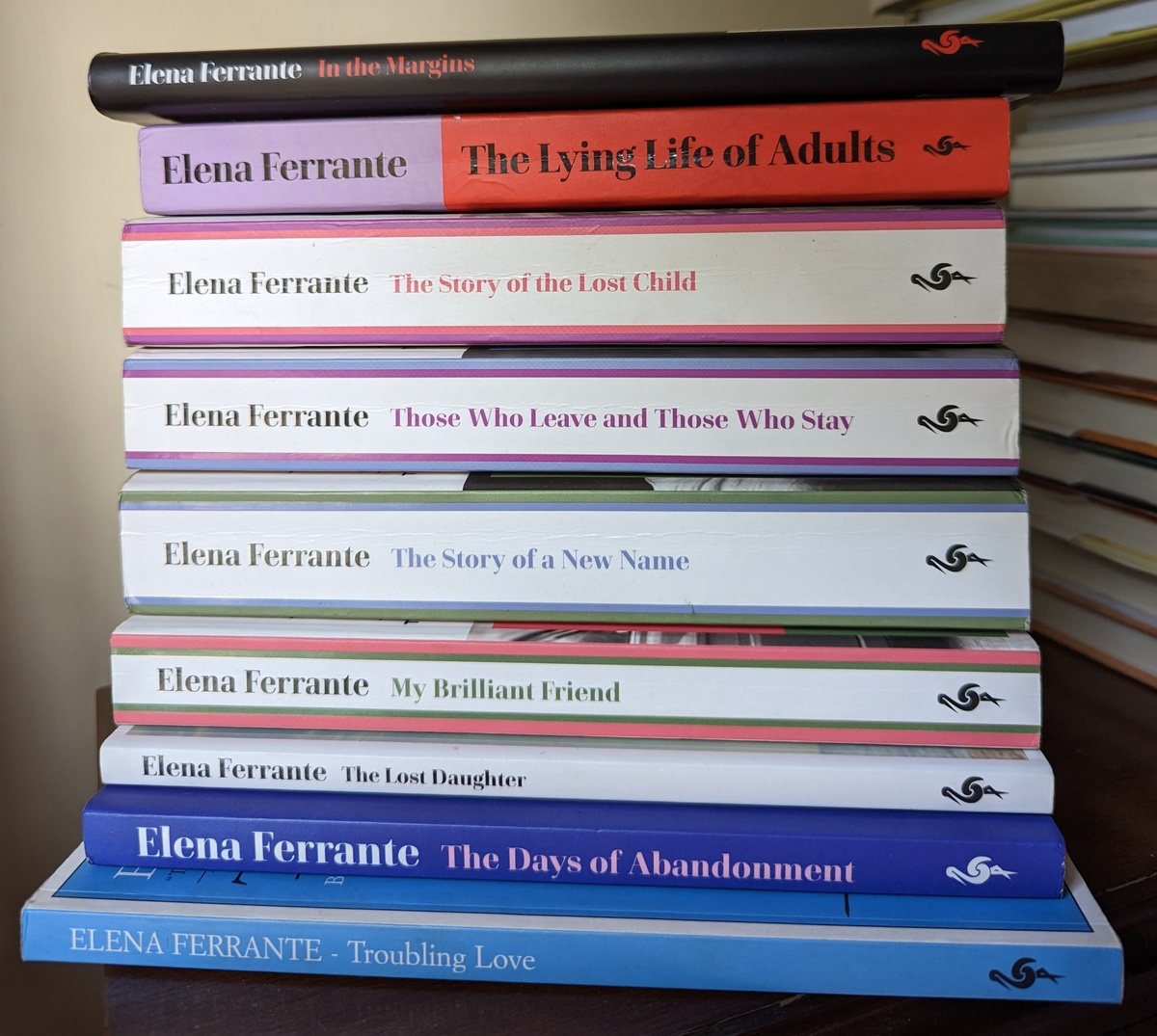

Books by Elena Ferrante. Photo: Ananya Dutta Gupta

For the real Elena Ferrante to be able to continue writing in Italian about Italy through the decades, about its political life and its class conflicts, the pseudonym is a necessity. In order to transform the real Elena effectively into a fiction, the real Elena must perforce remain a fiction.

So I got into the habit of using traditionally rigid structures and working on them carefully, while I waited patiently to start writing with all the truth I’m capable of, destabilizing, deforming, to make space for myself with my whole body. For me true writing is that: not an elegant, studied gesture but a convulsive act.

— Elena Ferrante, In the Margins, 15.

I was not supposed to be reading Elena Ferrante. The fact that I did is entirely owed to the mysterious algorithms of YouTube recommendations. Yet here I am, at the end of an uninterrupted reading spree spanning all eight of her fiction. Since writing this piece, I have extended that to In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing (2021), comprising Ferrante’s essays on her writing process. More committed enthusiasts of contemporary world literature may well frown upon my opening remark. After all, this Italian novelist who writes under a pseudonym has been a bestseller for over a decade now, and has a dedicated translator in New-York-based Ann Goldstein to share the credit for her worldwide popularity.

Even as I rarely succumb to the box office of books, I must admit to feeling piqued by the conundrum that is Ferrante’s popularity. Her anti-sentimentalist, Zola-esque refusal to sublimate interpersonal relations among adult and minors does nothing to court popularity, let alone populism. Ferrante’s ferocious determination to use the fictive mode to unmask what one protagonist calls “the ugliness of banality” should have been the prime reason for her unpopularity. Yet clearly that is not the case. How anomalous then is her runaway success? And how does that either confirm or upset our understanding of popularity? Such are my concerns in this essay.

Perhaps I missed the obvious? Ferrante is popular for the very reason that she does not set out to reinforce stereotypes about women and their lives. Her obdurate commitment to this strip search of women, men and children’s inner lives may well be the reason for her popularity. A relentlessly provocative exposé of love life and family relationships pivots all her plots. Her success stems from this late modern impulse, this refusal to separate the banal from the exceptional, or rather this persistence in finding the exceptional in the banal. Adult and family life in Ferrante is a largely inescapable vortex of tensions spearheaded by the uncontrollable dominance of people’s core instincts. Children get caught up partly by unavoidable proximity to erring adults and partly by their own inborn human susceptibility.

Fiction by its very nature lends itself to the excavation of visceral truths underlying the familiar masquerade of everyday social performances. Even drama, for reasons of the visual, performative compulsion, falls short of this mark. Take the case of language. Ferrante’s women and men alike fall back upon invectives in their Neapolitan dialect when they are angry. One wonders if the Italian narrator spells out these expletives in direct speech or politely refers to them the way the more discreet English translator does. In translation, it appears to suffice that the reader should register her characters’ uninhibited straddling of polished Italian and coarse Neapolitan as reported speech. Would this have worked in the theatres? One thinks not. Fiction can enact social and psychological realism precisely because it does not have to show any of this in action. And when fiction does contrive to use its fictiveness to reveal the unrevealed, its impact is raw and powerful. This is possibly true of the Ferrante phenomenon.

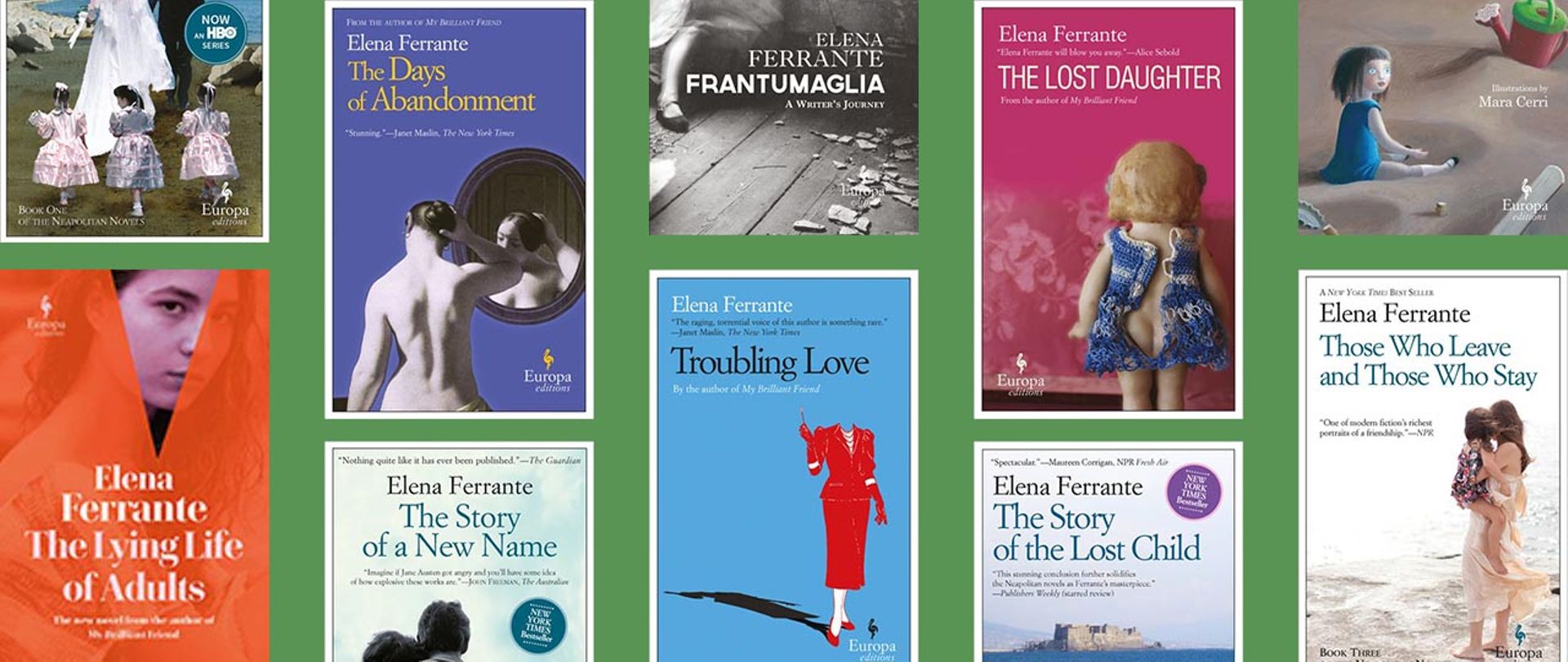

Ferrante’s chief protagonists are always women, across all the eight books; and she does not come across as a blatant apologist for them. Ferrante treats of women’s mind-space with hawk-eyed objectivity and without ethical preconditioning. Her women are not just flawed; they are spiteful, selfish, envious, manipulative, deceitful, irrational, aggressive, vindictive, just as often as they are kind, compassionate, intelligently resourceful functionaries in family and community. They are never cast as helpless victims of circumstances, at least not to the extent that they cannot take ownership of their choices or their conduct towards men, other women, children or elders. Take the example of The Days of Abandonment, that story of a woman irrevocably falling apart when her husband suddenly deserts her, and then just as slowly coming round, picking up her threads, and moving on. Far from hinging the narrative entirely upon a monologue of self-pity and lament, the book keeps a steady gaze on the complex, sometimes violent processes of mourning, which threaten to overturn the stoic equanimity demanded of a mother. Her caregiving falters, her attention slackens, her children suffer and become resentful of her. Sometimes she is able to make amends; at other times the rift ends up engendering far-reaching consequences for the filial bond. In short, Ferrante is remarkably unafraid to explore the gaps between the biological fact of motherhood and maternal feeling; and in predicating her women’s journeys around these unpalatable moments of conflicted self-realisation, the novelist manages to document the fraught history of women’s emancipation globally.

In The Lost Daughter, we meet a respectable writer and academic on vacation stealing a child’s doll and lying unabashedly to protect her own irrational desire to reclaim a slice of her own lost childhood. In The Lying Life of Adults, on the other hand, a chance remark by her parents prompts a young girl to go to unprecedented lengths to get to know her estranged aunt. That contact unleashes a chain of little actions ultimately resulting in the shocking disclosure of her father’s adultery and the eventual dissolution of their parents’ marriage. Troubling Love traces an estranged daughter’s traumatic efforts to piece together her lately deceased mother’s amorous secrets and her father’s abusiveness. Ferrante’s women, then, both perpetrate and endure suffering; and come through their ordeals using cerebral resources that are neither peculiarly feminine nor essentially moral. Her women are liberated from the burden of conforming to any idealised standard of feminine behaviour dictated by what Pierre Bourdieu calls habitus.

A still from the TV adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend

Those relatively disempowered and non-agentic are the immediately preceding generation. These older mothers, typically married off as young adults to local macho working-class beaus and fettered since to a lifetime of cooking and chores, are allowed their socio-cultural historicity and contexts for eliciting the reader’s empathy. The hauntingly portrayed broken-hearted Melina is a case in point. Nevertheless, the narrator’s gaze captures their animosity and jealousy towards their more vocal and agentic daughters, husbands, and siblings, without any extenuating moralisation.

This is perhaps the most emancipating aspect of being a woman reader of Ferrante. Her unsentimental delineation of women’s viciousness and fallibility, alongside her empathy with their struggles as self-willed, sexual beings, desirous of mobility, respite from the domestic grind, and financial independence, affords a fictional space for vicarious catharsis. As Ferrante herself puts it, her women are complex individuals united by what she calls an “understanding of love”. Such a sensitivity does not define itself in categorical opposition to negative feelings, but acknowledges them as forming an inevitable experiential element in all kinds of love. Women’s writing about women in conservative or traditional societies tends to interiorise a dual anxiety around the politics of representation. Either such writing is meliorative and conciliatory, lest such authors offend the need for women to seem sensitive to one another. Alternatively, women’s cultural construction of other women implicates itself in the patriarchally perpetuated binary of mulier bana and mulier mala, good women versus bad women.

The ground reality, particularly of working-class women’s interpersonal dynamics, in which ill will and camaraderie organically coexist, as among men, tells a different story. Much of women’s hostility towards other women might actually ensue from the natural differential in their willingness to conform to the exacting standards of appropriate feminine conduct. Although patriarchy is to blame for generationally sowing the seeds of this inter-female rivalry and animosity, the natural impulse of competitiveness and envy can hardly be ruled out as a reason for their perpetuation.

Ferrante’s women come across as relatable, and Ferrante seems to consider them qualified to be her female protagonist, only if they are brave enough to confront and endure the disclosure of their own venial, everyday cruelties towards their own sex, sometimes to their own mothers or daughters. All her chief protagonists demonstrate this self-tolerance and suffer the corresponding clinical candour that their creator and narrator subject them to. It is perhaps this fetish for repeating a kind of women, across age groups, that places Ferrante in the bracket that we ordinarily call “popular”. Cumulatively, she stands for a particular brand of alterity.

Another reason to maintain that Ferrante is a popular writer has to do with her style. Ferrante does not believe in disrupting the linearity of narratives over much. She starts dramatically at the end and then weaves the narrative systematically back to that end in a manner that never quite makes the story come full circle. Or, she begins at the beginning and yet manages to give it a sense of the fullness that is expected from the middle of a book. Non-linearity per se is not congruent with Ferrante’s brand of social realism and psychological naturalism. Even as truth for her is fluid, experiential and visceral, rather than concrete, singular and absolute, the truth of her protagonists’ lives is made up both of finite transience of moments and the slower seepage of years, decades and generations. In other words, her philosophy of time as a storyteller is largely traditional because her essential understanding of life experience is incremental. People change, yet they don’t; some prove lucky in certain ways, while others do not. Some make startling discoveries about themselves, their families, neighbours, lovers, friends; they drift apart, run away, suffer, grieve, learn, grow, come back, reconcile, fall apart again, go off on a tangent, come back, or don’t. This applies not just to her saga about friendship between Lénu and Lila in the Neapolitan Quartet, but to her single novels no less. Her protagonists’ stories of growth demonstrate that time does add to the quantum of understanding, although that understanding is not necessarily integrative or constructive in its function or telos. No essential pattern emerges from the passage of time. Time neither brings people together invariably, nor the reverse.

Olivia Colman in the Netflix adaptation of The Lost Daughter, directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal

However, the outcomes do follow in part from choices made, and one choice that the narrator seems to tacitly affirm on the merit of common validation as well as positive dividends is book learning and formal education. While several of Ferrante’s novels play out disparities in aspiration within a working-class, inner-city neighbourhood, the nature of these aspirations is essentially middle-class. Indeed, the non-judgemental representation of neighbourliness across economic class barriers notwithstanding, the murder of the corrupt, greedy local business family in The Story of the Lost Child does faintly read like a vindication of morals.

Ferrante’s life-view is conventional in so far as it upholds the power of education to save, preserve, or resurrect a semblance of its beneficiaries’ dignity and social value. This is more than evident in her alter ego Elena and her lover, the disappointingly fickle serial womaniser and man of letters Nino Sarratore’s, career trajectories. Who should turn out to be the good man though, but Pietro Airota, university professor and scion of the educated elite? Education, reading and writing as consummate survivor skills is also evident in her other woman protagonists. Ferrante’s narrator tries very hard to hide the awe that the educated evidently command among those who quit studies for circumstances or lack of will. Her self-aware protagonist in The Lying Life of Adults, that unsettlingly vivid dissection of the institution called family, exclaims, “I'm not wise, but I read a lot of novels.” Neither her admirer nor her readers are duly convinced by this attempt at ambivalent irony.

I found it telling that Ferrante should see in Dante’s Beatrice a remarkably progressive image of superior feminine intellect. All Ferrante’s women narrators-cum-protagonists participate in Lila and Lénu’s fantasy of emulating Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. Ferrante seems to be asking herself, what if those genteel nineteenth-century American sisters, including the rebellious Jo March, were siblings or childhood friends growing up in post-Second-War Naples?

Elena Ferrante’s novels are taken up with Italy and, particularly, inner-city Naples, from the experiential perspectives of both those who never left it and those who come and go. Her novels set off a dialogue, as it were, between the grand heritage of Renaissance Italian cities and their sordid post-Second-World-War underbelly. Yet this immersion in a specifically intra-Italian historiography does not appear to have deterred the global English-language readership!

All this goes to prove how cross-cultural identification between reader and fiction not only transcends specificities of place and time, but can actually stem from those very specificities. That is not to say all people everywhere behave exactly the same way. Rather, many people under similar socio-economic circumstances may end up behaving similarly, or at least might recognise a similar range of behavioural stimuli and triggers, even if they do not act upon them. Such then is the plausibility factor driving realism as a mode. Else, Satyajit Ray would not have been able to relate to Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, that quintessentially Italian film about little everyday struggles in the city. This mention of De Sica is not random; for the most abiding flavour of Ferrante’s works is neo-Realist and decidedly urban. The semi-autobiographical Neapolitan novels take off from around the same time as De Sica’s post-Second-World-War classic about urban hardships.

The recurrence of the un-stereotypically typical Ferrante woman and the recurrent centrality of inner-city Naples incline the reader to identify Ferrante’s fiction as essentially life-writing, the mode that won Annie Ernaux the Nobel Prize last year. Ferrante has distributed her own life and milieu across these stories with such shocking honesty that she could not possibly have written these in her own name. Expectedly, therefore, Elena Airota, née Greco, the narrator of the entire Neapolitan Quartet, reveals in the last of the four books, The Story of the Lost Child, how she was ostracised by most of those whom she had grown up around for showing them, their neighbourhood, their venalities in a true light.

For the real Elena to be able to continue writing in Italian about Italy through the decades, about its political life and its class conflicts, warts and all, the pseudonym is a necessity. In order to transform the real Elena effectively into a fiction, the real Elena must perforce remain a fiction.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated