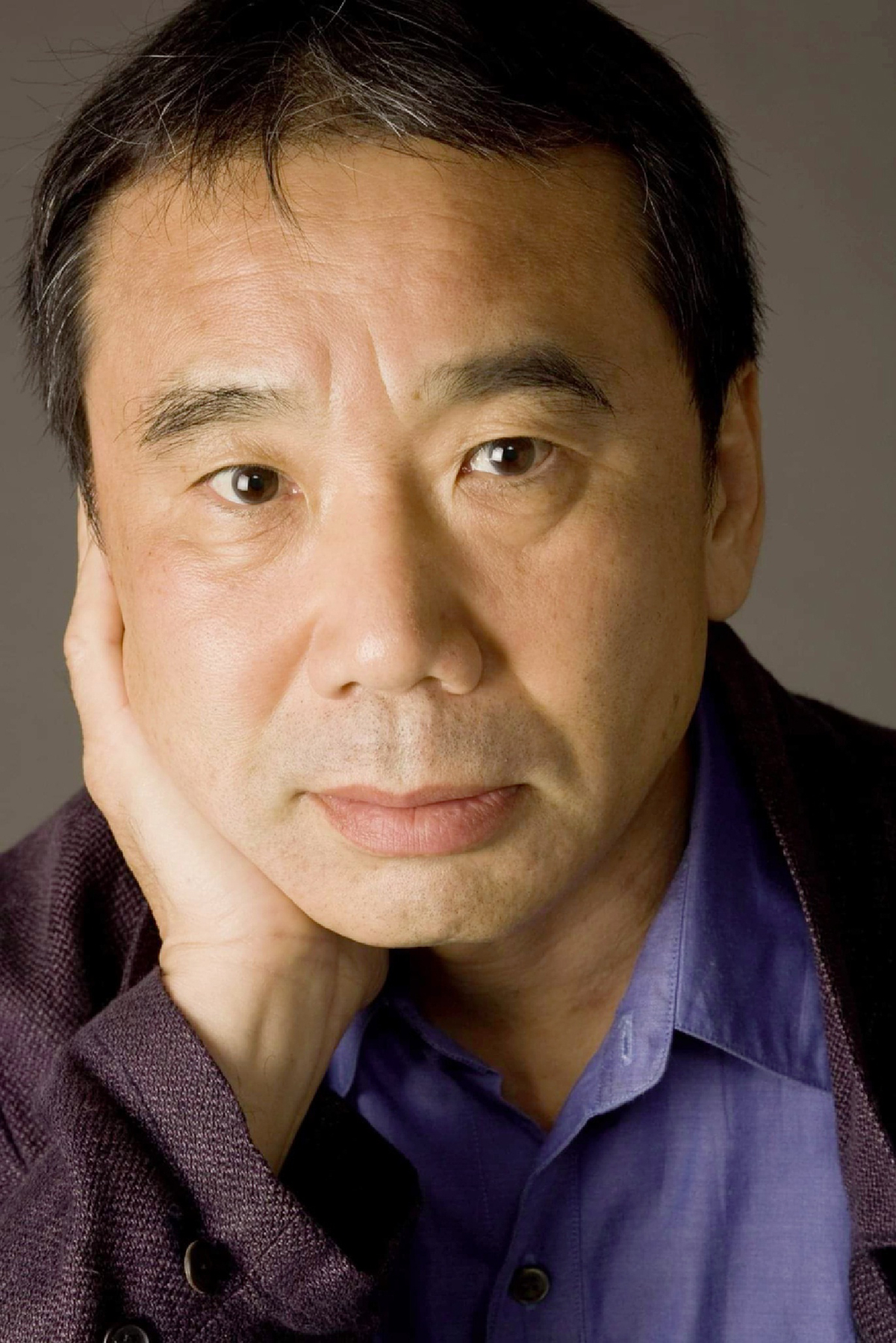

Haruki Murakami. Photos courtesy of the author’s official Facebook page

What Japanese writer Haruki Murakami, whose books sell in millions, means and why he matters

What do we talk about when we talk about Haruki Murakami? How should an essay on one of the world’s best-known writers, whose books sell in millions, be written about? What symmetry words should follow? What pattern? What caverns of self must one enter? What realm of dream? Must one flit between two different worlds or narratives, real and unreal, to capture the essence of his style or inhabit a different space, an inscrutable zone to write his story, like Murakami, 70, does himself when he writes his books? Should one go back to jazz records and intersperse their rhythm with the texture of the text or mention about a feline one has taken a shine to? What one must do to evoke the man, who likes to discover new things about himself, and his dream-like, gossamer prose, through which he keeps delving into the vast swathes of the dark, the unknown and the unfamiliar? Should I enumerate the unexpected, often bizarre, twists and turns his stories take or dwell instead on the lone alienated narrator of his stories or his other characters, hurtling between the real and the surreal, natural and the supernatural occurrences?

How does an admirer of Murakami write about the man, the magic, the mystique? Would a few paragraphs capture the incredible, and ineffable, magic he weaves in his stories and novels? And, since his recent novel — Killing Commendatore (Penguin Random House, 2018; Murakami’s ode to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby) — is a doorstopper, like IQ84 (Penguin Random House, 2011), would the volume of the essay be a key in piecing together his profile or just drawing a jigsaw puzzle or a maze of words — leaving behind some vague references, some clues that, in the end, help readers get an entry into his dark, mysterious, impenetrable world — would do the trick?

If, like me, you are an admirer, you perhaps already know what Murakami means and why he matters. If you are still alien to his world, you will do yourself a favour to enter it once and find yourself transformed for life. If you are someone who has read all his works, and are getting increasingly weary of the usual tropes, the Murakami Bingo, he keeps taking resort to, despair not. Murakami always has surprises up his sleeve. You never know what he comes up with next and seize your senses.

Murakami has a way of not just getting into the skin of his characters, but also their minds, their psyche, what makes them who they are, why they think the way do, how their past, imperfect, shapes them and their future — indefinite, uncertain. So, how does Murakami does what he does? A key to understanding his craft is to understand the man, his methods and his madness. In an interview to Asahi Shimbun newspaper in Japan on March 18, Murakami says that in his stories, he likes to leave blanks, “just like omitting the root from the chord in jazz”. He says he likes “mandala-like” things, in which another story is connected by a mysterious tunnel. For him, when he writes his characters, what’s most important is “wall-penetrating”. “After thinking for a long time, the protagonist is connected to another world. Deep in his psyche, he finds a doorway. The ‘wall-penetrating’ that was first introduced in Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1997) unleashed my novelistic imagination and became a detonator for the story,” he tells the newspaper.

To Murakami, who usually starts his books with a singular image, a title, a line or just a few opening paragraphs, what’s important is “how things look, how they sound and how the vibration from them is felt, not things themselves”. He tells Asahi Shimbun: “What I want to do is to have readers establish the essence of things from the sum (of those perceptions). It is like a joint work between me and readers.” In his writings, the world gets condensed, realities distilled and served with a dash of the uncanny. Deborah Treisman, fiction editor at the New Yorker, who interviewed Murakami in February this year, writes: “His narratives are almost always inquisitive, exploratory. His heroes, hapless or directed, set off on missions of discovery. Where they end up is sometimes familiar, sometimes profoundly, fundamentally strange. A subtle stylist and a self-willed Everyman, Murakami is a master of both suspense and sociology, his language a deceptively simple screen with a mystery hidden behind it. In his fiction, he has written about phantom sheep, about spirits meeting up in a netherworld, about little people who emerge from a painting, but, beneath the evocative, often dreamlike imagery, his work is most often a study of missed connections, of both the comedy and the tragedy triggered by our failures to understand one another.”

Talking to Treisman, Murakami mentions how readers often tell his that there’s an “unreal world” in his work — that the protagonist goes to that world and then comes back to the real world. “But I can’t always see the borderline between the unreal world and the realistic world. So, in many cases, they’re mixed up. In Japan, I think that other world is very close to our real life, and if we decide to go to the other side it’s not so difficult. I get the impression that in the Western world it isn’t so easy to go to the other side; you have to go through some trials to get to the other world. But, in Japan, if you want to go there, you go there. So, in my stories, if you go down to the bottom of a well, there’s another world. And you can’t necessarily tell the difference between this side and the other side,” Murakami tells Treisman.

When Murakami writes a story, he seems to take a long, hard look at its contours, exploring the most magical, and the most bizarre way it could unfold, exploring possibilities, upending the normal. “When you write stories, you must not look away from it,” he tells Asahi Shimbun. A favourite Murakami line, spouted by his characters, is: “Things are not what they seem.” Writing about things that are not what they seem entail delving into the unfamiliar. Familiarity can be boring. “What’s the fun in writing about things that readers already know about?” the author once said.

Murakami’s world is like a portal to an alternate, parallel universe where things have their own way of happening, where reality and unreality collide in exuberant, and elegant, bursts, somewhere beyond time and space, not hamstrung by worldly reason or logic. Murakami’s writing, it seems, springs from a deep well within his self, which he has talked about and found a way to put in some of his novels — the well as a metaphor for a dark, mysterious place which takes you away from the mundane realities and banal concerns of the world to a zone where you reflect on the bigger questions — for example, life and death, purpose of existence or the ennui of everyday humdrum human existence.

Having been alone in a dark pit is part of Murakami’s childhood memory. He was born in 1949 in Kyoto into the middle-class family of Chiaki and Miyuki Murakami — both his father, son of a Buddhist priest, and mother, daughter of a merchant from Osaka, taught Japanese literature — he was raised in Kobe, where a lot of US soldiers were stationed, and which shaped his sensibility. Since an early age, Murakami identified more with the world outside Japan, especially the US, and consciously stayed away from Japanese literature, art, and music. During his stay in Tokyo as a student of drama at Waseda, one of Japan’s top universities, in the late sixties, Murakami gravitated towards post-modern fiction. He married Yoko Takahashi, whom he had met at Waseda, when he was twenty-three and spent the next several years of his life running a jazz club in Tokyo, Peter Cat, till he wrote his first novel, and the first part of Trilogy of the Rats series, Hear the Wind Sing (in 1979 in Japanese, followed by its English translation in 1987), on a whim. The novel’s success made it possible for Murakami to sell off his jazz club and become a full-time writer.

As a child, Murakami had strayed into a pit and was rescued by his mother. That early memory keeps making its appearance in various forms in his novels. So much so that he once said that his life’s dream was “to sit at the bottom of a well”. In Killing Commendatore, he makes the narrator, an artist whose wife has left him, and Menshiki, a mysterious multi-millionaire modelled on Jay Gatsby, do exactly that.

For Murakami, to write is to connect with a deep core of his self. Murakami told Sam Anderson in a 2011 interview with the New York Times: “I live in Tokyo, a kind of civilized world — like New York or Los Angeles or London or Paris. If you want to find a magical situation, magical things, you have to go deep inside yourself. So that is what I do. People say it’s magic realism — but in the depths of my soul, it’s just realism. Not magical. While I’m writing, it’s very natural, very logical, very realistic and reasonable.” When he is working on a novel, Murakami finds himself at his desk every morning. But that’s in the realistic world, he tells Treisman, adding that once he starts writing something takes over. “I go somewhere else. I open the door, enter that place, and see what’s happening there. I don’t know — or I don’t care — if it’s a realistic world or an unrealistic one. I go deeper and deeper, as I concentrate on writing, into a kind of underground. While I’m there, I encounter strange things. But while I’m seeing them, to my eyes, they look natural. And if there is darkness in there, that darkness comes to me, and maybe it has some message, you know? I’m trying to grasp the message. So I look around that world and I describe what I see, and then I come back. Coming back is important. If you cannot come back, it’s scary. But I’m a professional, so I can come back,” he says.

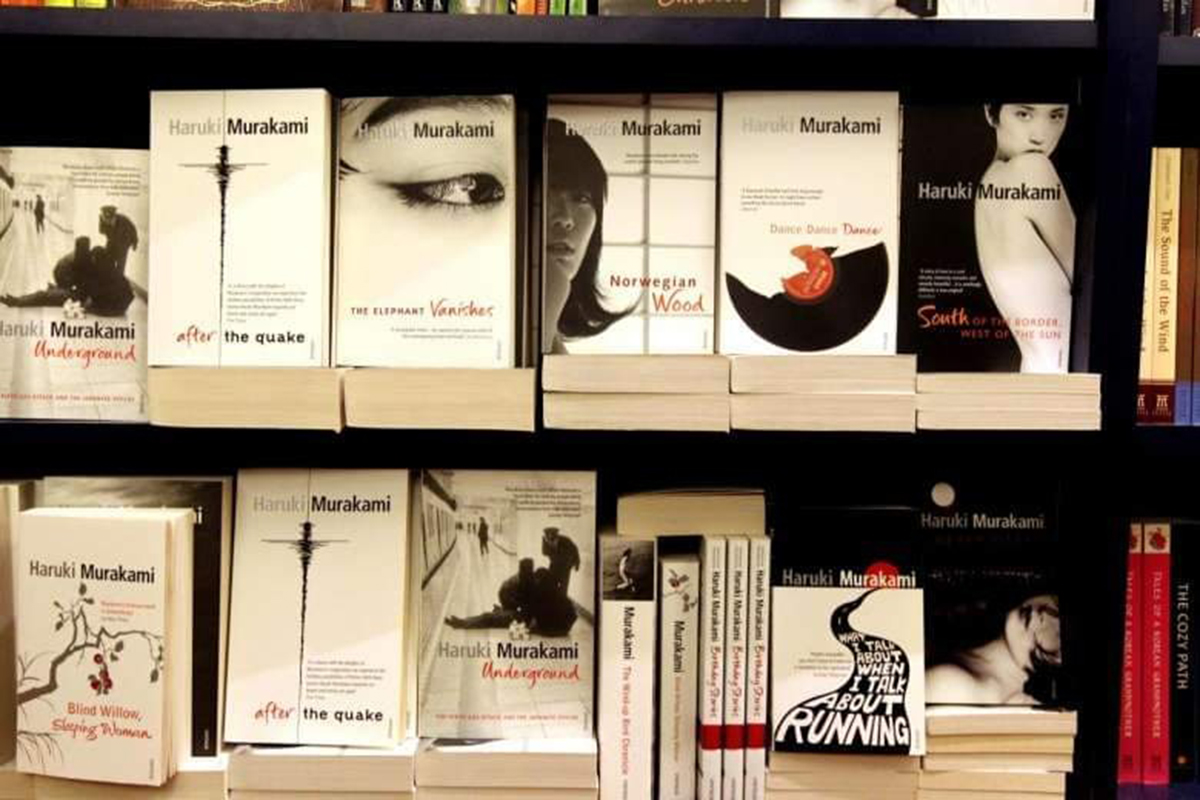

Murakami has been into that underground and back for far too many times, and has now perfected the art of finding his way out, after finding magic that he sprinkles across his prose. As a writer, Murakami is interested in shedding light on the mystifying labyrinth within the dreams and minds of his characters. J. Philip Gabriel, Professor of East Asian studies at the University of Arizona — who has translated major works by Murakami, including Kafka on the Shore (2005, for which he was awarded the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Prize), South of the Border, West of the Sun (1999); 1Q84 (Book 3, 2011) and Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman (2006, with Jay Rubin), among others — says that Murakami’s themes are relatable to readers, and readers have come to expect his stories, in some way or another, to straddle the real and the surreal. “This gives a recognisable otherworldliness to his narratives, though, in the end, I think his characters are grounded in the real. In other words, they come back to trying to solve real-life problems. The fact that he isn’t trying to be overtly literary also helps explain why, to me at least, his stories work. They are approachable in a way more openly experimental, postmodern literature is not,” Professor Gabriel tells The Punch Magazine.

The signature pleasure of a Murakami plot, writes Anderson, is “watching a very ordinary situation (riding an elevator, boiling spaghetti, ironing a shirt) turn suddenly extraordinary (a mysterious phone call, a trip down a magical well, a conversation with a Sheep Man) — watching a character, in other words, being dropped from a position of existential fluency into something completely foreign and then being forced to mediate, awkwardly, between those two realities”. He writes that a Murakami character is always, in a sense, translating between radically different worlds: mundane and bizarre, natural and supernatural, country and city, male and female, overground and underground. “His entire oeuvre, in other words, is the act of translation dramatised,” writes Anderson.

“The fact that I have been able to become a professional working novelist is, even now, a great surprise to me,” Murakami wrote to Anderson in an email three days before the release of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage in 2011. He added: “In fact, each and every thing that has happened over the past 34 years has been a sequence of utter surprise.” Anderson writes: “The real surprise, perhaps, is that Murakami’s novels now incite a similar degree of anticipation and hunger outside of Japan, even though they are written in a language spoken and read by a relatively small population on a distant and parochial archipelago in the North Pacific.”

If you want an inroad into the enchanting, magical world of Murakami, you should not merely be a reader, books must have “happened” to you. You should also have an ear for the music since Murakami writes as if he is “making music” — the writer told this to Seiji Ozawa, former conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, in a series of conversations in Absolutely on Music (2011). “Rhythm, after all, is the most important thing. Like love, there can never be too much music,” Murakami told Ozawa.

“He is certainly a fan of Western music, film, and literature and this is clearly seen in the myriad references to these scattered throughout his works,” says Professor Gabriel, adding that the author’s references include Jazz, classical music, John Wayne films, and (Jean-Luc) Godard, instead of more Japanese items. “This, arguably, makes him easier for Western readers to understand and appreciate, says Professor Gabriel, adding that he finds it interesting that his characters’ literary preferences are a little anachronistic at times. “They read Balzac, Proust, Conrad — one character in Norwegian Wood (published in Japanese in 1987, and in English in 2000) even says that if you’re only reading what other people read, then your thinking will be the same as everyone else’s. In a similar way, with his use of magical realism and the juxtaposition of the real and the surreal, I think Murakami is urging us to question the obvious, and dig deeper, and to not accept the conventional but to seek what truly moves us,” says Professor Gabriel.

Like music, love is central to Murakami’s world. The relationship between men and women is like a chiaroscuro, with its share of light and shade; the two sexes keep falling in and out of love. Also crucial in his writing is loneliness — either innate or acquired. In one of his stories in Men Without Women (2014), a man lets solitude, silence and loneliness soak in like “dry ground welcoming the rain, seep down inside his body like a “red-wine stain on a pastel carpet”. Sex remains on the horizon, too, and, in some of his novels, is described in minute detail. The narrator in Killing Commendatore, for instance, has a vivid dream about making love with his wife after she leaves him.

Professor Gabriel says that when he first encountered Murakami’s writing way back in 1986, the writer struck him as someone unique in contemporary Japanese literature, a writer who “was not caught up with tradition or the past, but who was trying to forge a new way, and a new style for Japanese fiction”. He says: “I first encountered his short stories, in two early collections. I’d never read anything in Japanese before quite so engaging, and was reminded of two of my favorite writers from my college days, Kurt Vonnegut and Richard Brautigan. They all share a desire to convey something important and necessary, but in an approachable way, with a sometimes quirky take on life.”

According to some readers, his quirkiness and the use of “predictable” tropes, however, have begun to tire them. “Murakami? Aargh! Can’t stand him anymore,” said one reader, requesting not to be named. So, has Murakami begun to bore his readers, introducing them to a sense of fatigue? “I don’t know about fatigue among readers, though I have heard comments about repeated themes and tropes. In any story, we find pleasure in the combination of the predictable and the unpredictable, and I always find Murakami’s work to be an engaging blend of the two, in balance. Just at the point in the narrative where I think I’m on top of things, he will surprise me. Killing Commendatore and the pit reminded me, of course, of Wind-up Bird Chronicle’s well — a variation on a theme, perhaps — but in the former he adds the element of the deceased sister and the search to reclaim memories of her. The story “The Wind Cave” in last September’s The New Yorker, which combines elements from two disparate chapters of Killing Commendatore, underscores this point,” says Professor Gabriel, adding that for some time now, there has been a growing sense of “empathy” in Murakami’s lead characters, which is perhaps more evident against the background of some reworked themes and imagery.

Killing Commendatore, says Professor Gabriel, successfully pulls off a homage to a beloved writer’s works. Interested readers, he says, may have noted the nod to, for instance, Faulkner in the story “Barn Burning” (the title, of course, and the early version of the story, which had the main character reading a volume of Faulkner’s short stories). There is a nod to The Great Gatsby in Norwegian Wood; towards the end of chapter two, the character reaches out to the green light of the receding firefly. “Since Gatsby is a novel Murakami admires, and one he has translated into Japanese, I was long expecting it to reappear as more than a passing reference, and indeed it has in his latest work,” says Professor Gabriel.

If Murakami writes about the dark, it only adds to his allure. Modern literature, says Professor Gabriel, often seems to me to be more on the tragic and dark side. “And Murakami, of course, himself deals with some dark issues — suicide, loss, war — yet there is the expectation with his work that there may be a faint glimmer of hope in the distance. Not with every work, but with many of his works this is true. Feeling ever so slightly hopeful, and uplifted, is not a bad feeling to end with when you read a novel,” he says.

The lines from Murakami’s books have captured the imagination of the young, the lonely and the restless, and have become quotable quotes. “More or less all of us want answers to the reasons why we’re living on this earth,” writes Murakami in Underground (2010), his sole foray into journalism, in which he interviews 60 victims of the 1995 Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway. “I have to write things down to feel I fully comprehend them,” he writes in Norwegian Wood. Sample some more:“Life is not like water. Things in life don’t necessarily flow over the possible short route (IQ84); Everyone may be ordinary, but they’re not normal (Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, (1985, 1991). Memory is like fiction; or else it’s fiction that’s like memory (The Elephant Vanishes, 1980-1991, 1993).

“My short stories are like soft shadows I have set out in the world, faint footprints I have left,” Murakami writes in Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman, which he considers to be his first “real” short story collection. As a writer, Murakami is something of a stormtrooper, the ground force of his self-created enigmatic literary empire, wherein he keeps wandering, driven by the passions in his life, charting his own paths, leaving the soft shadows of his thoughts, and creating distinct, not faint, footprints on the sands of time.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated