The beloved like the sun will gleam

The lover like an atom will spin

When love’s spring zephyr begins to stream

Every branch not dead will begin to swing

— Rumi1

A place is just a place. That uplifting divine in a mosque, a church, a synagogue,

or a temple is the vibration of the Creator inside of us—the lover and the beloved

in union, forever entwined like the braid of our genes.

or a temple is the vibration of the Creator inside of us—the lover and the beloved

in union, forever entwined like the braid of our genes.

In the path of desire, the wise and the foolish are as one

In the ways of love, the friend and strangers are as one

Those gifted the wine of union with the beloved

In their creed, God’s House and idol temples become as one

— Rumi2

This is how I enter every mosque: with a covered body and a naked soul. I pray inside my eyes, inside the cave of my own being. I say words without the aid of breath, think thoughts with my spirit, bow before no one except whatever helps me fit into the heart of humanity.

Sometimes hidden and sometimes revealed am I

Sometimes a Muslim, a Christian or a Jew am I

To fit my heart into everyone else’s heart

Each day someone other and new am I

—Rumi3

But the open spaces are reserved for men. Only men.

I hum prayers under my breath, under every ravishing dome of each mosque,

beneath its delicate beauty, among the souls of the artists who gave eyes, backs, hands

and souls to its grandeur.

beneath its delicate beauty, among the souls of the artists who gave eyes, backs, hands

and souls to its grandeur.

Women must huddle behind ropes and wooden barriers, on the periphery, the

other side, like chattel, covered head to toe. They kneel side by side, stand up in

prayer. They crush me between the pillows of their hips.

other side, like chattel, covered head to toe. They kneel side by side, stand up in

prayer. They crush me between the pillows of their hips.

Men pray freely, directly under the dome. I watch them with a sense of

dissonance. This needles that dangerous part of me I call RED, because she is red — the

rebellious woman I strain to keep under check.

dissonance. This needles that dangerous part of me I call RED, because she is red — the

rebellious woman I strain to keep under check.

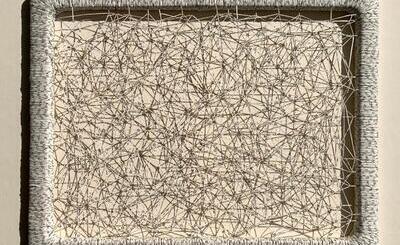

At Shams-i Tabrizi’s tomb,

the mosque’s wall-to-wall

machine-made carpet is red.

I break the rules, shun the women’s

section behind ropes, back and black,

out of the way, sit against a wall beneath

a large framed plaque of His name,

the calligraphy like long entwined fingers

of a goddess with endless golden nails.

Perhaps this is sacrilege, the wrong place to sit under His name.

But no one looks, no one comes to gather and reprimand, to shoo this female to

where she belongs, behind that rope, out of the way. Of men.

where she belongs, behind that rope, out of the way. Of men.

I watch the Pashtu poet among us, the one with ties to Taliban, the man of religion

in his customary white garb and black Western jacket, the dark man who never says

much, smiles almost never, and watches everyone with eyes impossible to read.

in his customary white garb and black Western jacket, the dark man who never says

much, smiles almost never, and watches everyone with eyes impossible to read.

He comes, comes towards me,

a dark coiling cloud (promise of rain?)

stops short, then lifts up his long

arms and his suddenly beautiful

bearded face, in prayer.

Now certain I am sitting

where I must not, a blasphemy in red,

beneath the Creator’s entwined golden name,

I gather my knees, hold them tight

like children in need of cheer and shield.

He bends and unbends,

lifts large palms up towards

the sky beyond this dome

where blue is light’s twisted lie.

I see dusty roads outside, fields

we have just passed, the sheep grazing in brown

pastures, a line of geese ambling by the side

of the road, the olive trees like rows of devoted

worshippers rooted to earth, and to us.

Yesterday I greeted my fellow writers with a Dervish greeting. This is how: you

take a friend’s hand, entwine it in your own, then kiss it, and allow it to be kissed.

take a friend’s hand, entwine it in your own, then kiss it, and allow it to be kissed.

When it was his turn, I took the Pashtu poet’s hands. Something in his eyes warn-

ed me to not put my lips on his skin (so dark and soft), to not offer my own hands to

his lips (trembling).

his lips (trembling).

He mutters words.

Sparrow song. Bows,

puts his forehead

to the ground, his hair

so black not even light

escapes the straight strands.

Watch him pull me into his

event horizon, suck me

into his wormhole on the other

side of which he still

prays, except that here, in this

alternate universe,

he bows not before a god

but before me,

this female blinking danger,

soft, strong and RED,

refusing

his black, refusing his white.

RED who knows when to give,

what and how to take.

RED who is the explosion

in Shams, the dance in sama,

the music in Rumi’s whirling words, a sky

on fire, the heart of the third planet,

even the curled strands of this carpet

on which a thousand praying men

lay their foreheads. RED,

the shawl on my head, on my soft,

bare shoulders, RED, the ink, the blood,

also your eyes when angry (or in lust?)

In this universe, my Pashtu friend, my fellow poet, you pray to this, this immutable RED, the color that refuses...

__________________________

Notes

1. Rumi, JalÄl ad-DÄ«n Muhammad, DÄ«vÄn-e Šhams-e TabrÄ«zÄ«, 466 (Tehran, Iran: University of Tehran Press, 1363 Shamsi), Badiozzaman Forouzanfar, editor.

.

2. Rumi, JalÄl ad-DÄ«n Muhammad, DÄ«vÄn-e Šhams-e TabrÄ«zÄ«, 306 (Tehran, Iran: Amir Kabir Publishers, 1341 Shamsi), Badiozzaman Forouzanfar, editor.

3. Rumi, JalÄl ad-DÄ«n Muhammad, DÄ«vÄn-e Šhams-e TabrÄ«zÄ«, 1325 (Tehran, Iran: Amir Kabir Publishers, 1341), Badiozzaman Forouzanfar, editor.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated