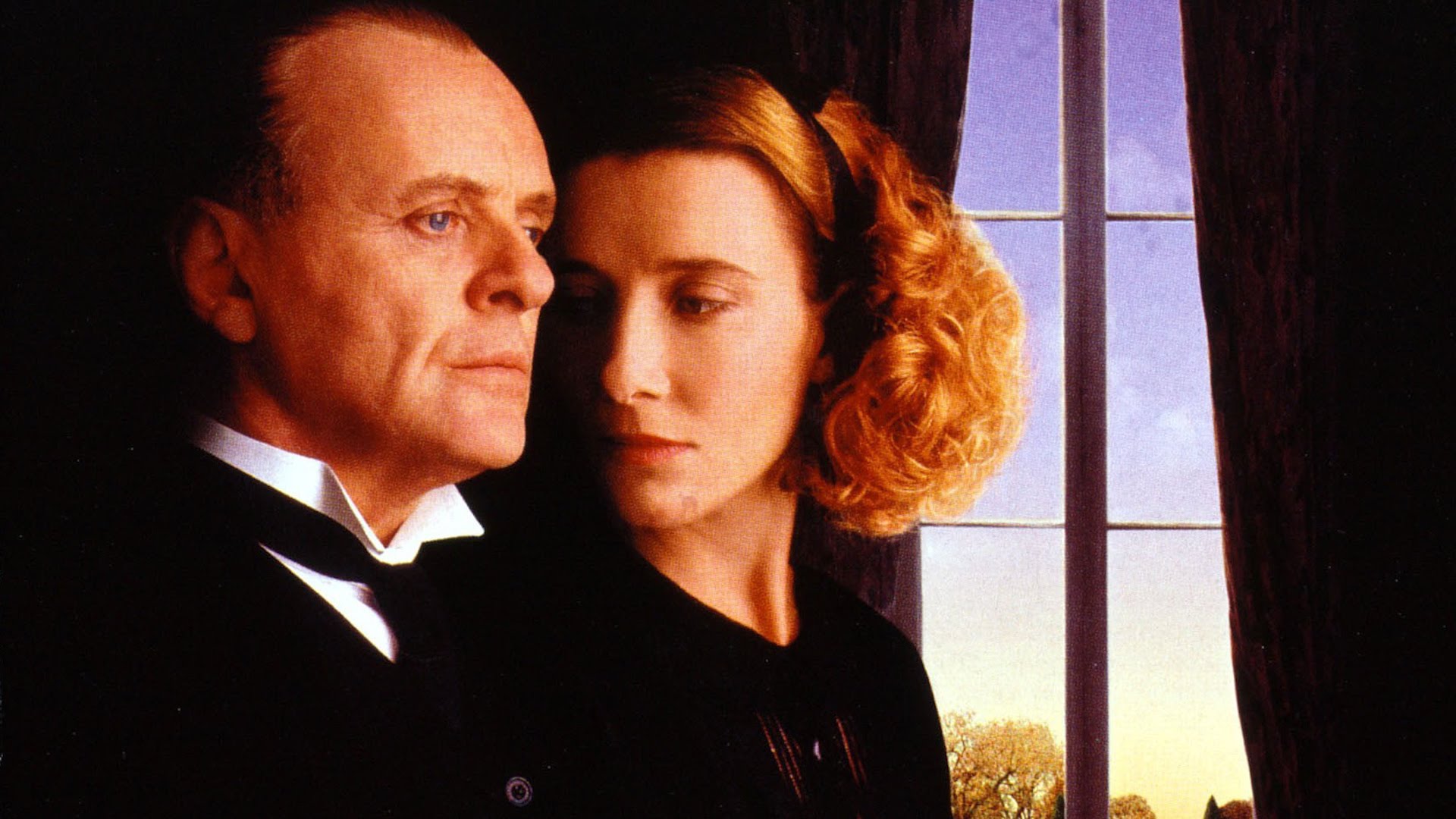

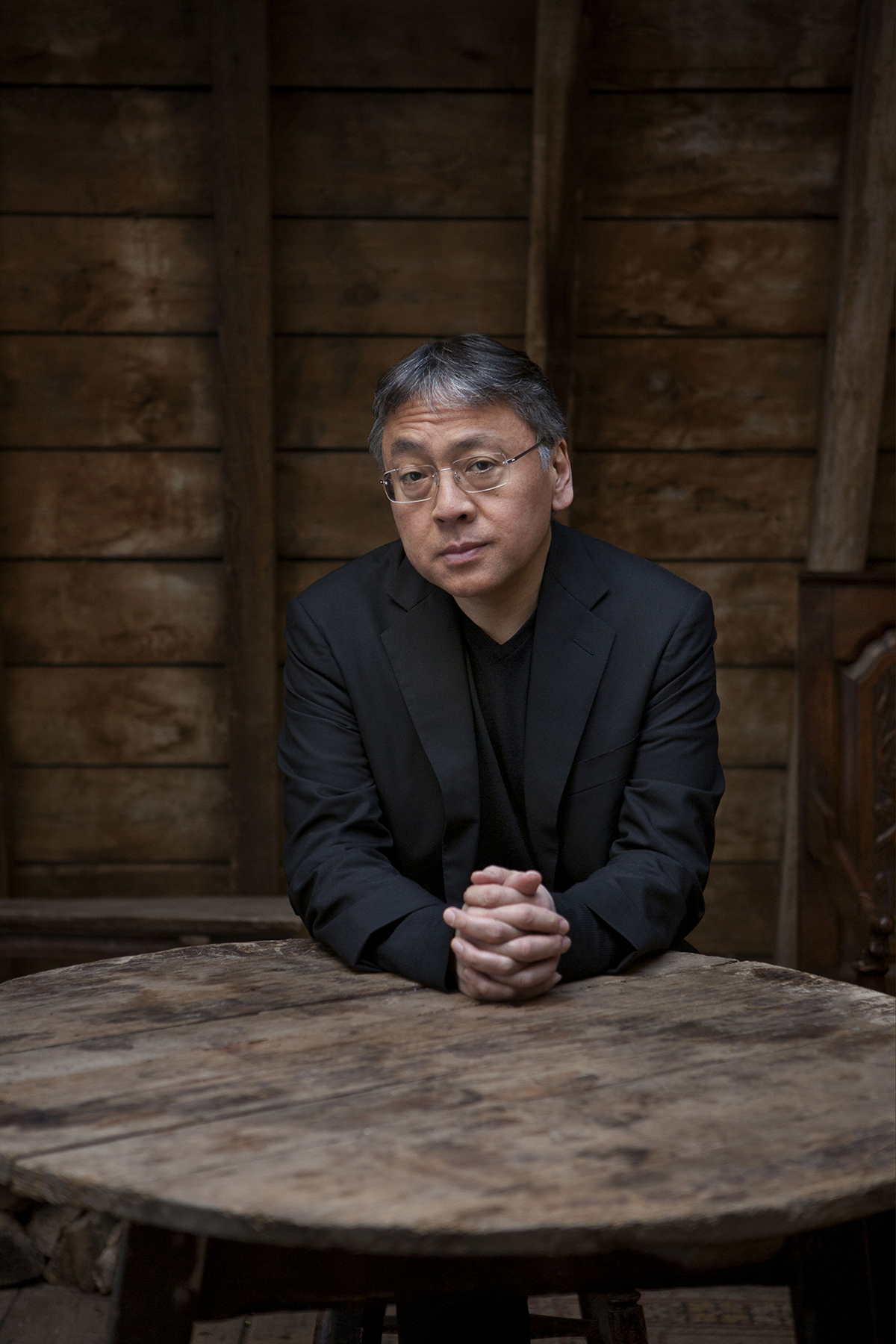

Kazuo Ishiguro. Photo: Jeff Cottenden, courtesy of Penguin Random House

Kazuo Ishiguro, the winner of the 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature, blends public and private realms to explore the texture of memory

Kazuo Ishiguro, the winner of the 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature, transports us to a realm where public history and private memory create both harmony and dissonance. In his novels, public and private realms intermingle — and in their intricate intermingling, and delicate tension, lies Ishiguro’s enduring appeal. He is a writer of unfettered imagination and undeterred ambition. A realist and an absurdist at heart, Ishiguro (62), in his career spanning three-and-a-half decade, has broken new grounds with seven novels and a collection of interlinked stories.

In a statement, the Swedish Academy wrote that Ishiguro, “in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.” However, in an interview posted on the Nobel Prize website, Ishiguro elaborated on his interest in worldly connections, stating: “One of the things that’s interested me always is how we live in small worlds and big worlds at the same time: that we have a personal arena in which we have to try and find fulfilment and love, but that inevitably intersects with a larger world, where politics, or even dystopian universes, can prevail. So I think I’ve always been interested in that. We live in small worlds and big worlds at the same time and we can’t … forget one or the other.”

Ishiguro’s territory, therefore, encompasses several worlds — both small and big. These are worlds that contain many worlds, blending the private and the public, mixing the personal with the political. His territory is also the texture of memory. In a 2005 interview, after the release of his novel, Never Let Me Go, which revolved around cloning and bioethics, Ishiguro said: “I’ve always liked the texture of memory. I like it that a scene pulled from the narrator’s memory is blurred at the edges, layered with all sorts of emotions, and open to manipulation. You’re not just telling the reader: ‘this-and-this happened.’ You’re also raising questions like: why has she remembered this event just at this point? How does she feel about it? And when she says she can’t remember very precisely what happened, but she’ll tell us anyway, well, how much do we trust her?... I love all these subtle things you can do when you tell a story through someone’s memories.”

Like the artist of one of his novels, Ishiguro is the writer of a floating world, a world where everything is in a state of perpetual flux, a world in the throes of uncertainties — of memories, space and time. In novel after ingenious novel employing unreliable first-person narrators, Ishiguro, in pared-down prose, explores the various ways memory shapes identities. If memory fades or gets suppressed or distorted, it has its pitfalls: it can suppress and distort personal histories, memories of people, their recollections of who or how or what they were once. Ishiguro shows us how we — as individuals, societies and nations — suffer with the inherent inability to face the past and how we reconcile with that “foreign country”, each of us in our own way. In his novels, we discover how individuals — and societies — remember and forget.

To Ishiguro, everything begins with the germination of an idea in the crevices of his mind which is fermented with imagination, often through taking recourse to fragments of consciousness. As his characters unravel their often-uncomfortable memories, excavating their past, he makes the narrative glide. In an interview with Cody Delistraty in The New Yorker, Ishiguro said that ideas come first and he decides on the settings only later. “The important thing is making the story fly,” he said.

This is no mean task, especially for a writer who is interested in going beyond the “marketing labels” of genres and doing his own thing: now wrestle with memory or history or cling to the flight of fantasy or showing how the boundaries between imagination and life can evaporate. Reading Ishiguro is to realise that literature is a mirror of life.

A Life Less Ordinary

Born in Nagasaki, Japan, in 1954, Ishiguro moved to England when he was five. His mother, Shizuko, was in Nagasaki when the atomic bomb was dropped. His father, Shizuo, who was brought up in Shanghai, was an oceanographer. The family moved to Guildford, southern England, after the head of the British National Institute of Oceanography invited Shizuo over to join the British government’s research project on the North Sea. In a 2008 interview to The Paris Review, and several other interviews at different points of time, Ishiguro said he grew up attending British schools, but speaking Japanese at home with his parents. He also said that the expatriation was originally intended to be short-term and well into his adolescence, he — and the family — expected that they would one day return to Japan. However, as time flew, their sojourn became permanent. Ishiguro, the native of Nagasaki, never returned.

In 1973, after completing school, Ishiguro took up a clutch of odd jobs, including working as a grouse-beater for the Queen Mother at Balmoral Castle, Scotland, for a brief period. In April 1974, he travelled to the US and hitchhiked around the west coast for several months, seized with the “carefree, youthful idealism” that pervaded the air then and has come to define that era. Later that year, Ishiguro took up a course of study at the University of Kent in Canterbury, where he did B.A.in English and Philosophy. After a year, he took another year out and spent six months working as a volunteer community worker on a housing estate in Renfrew, Scotland.

After completing his B.A. in 1978, Ishiguro went back to social work. For a while, he was based in London and worked for the Cyrenians, an organisation that seeks to meet the needs of the homeless, where he met his future wife, Lorna Anne MacDougall.

As a student, Ishiguro was heavily into detective stories: he was obsessed with Sherlock Holmes. The other obsession was rock music, he tells The Paris Review in an interview. He had played the piano since he was five. He started playing the guitar when he was 15 and started listening to pop records (Tom Jones) when he was about 11. When he was 13, he bought John Wesley Harding, which was his first Dylan album. He says in the interview that he knew Bob Dylan as a great lyricist. “With Dylan, I suppose it was my first contact with stream-of-consciousness or surreal lyrics. And I discovered Leonard Cohen, who had a literary approach to lyrics. He had published two novels and a few volumes of poetry. For a Jewish guy, his imagery was very Catholic. Lot of saints and Madonnas. He was like a French chanteur. I liked the idea that a musician could be utterly self-sufficient. You write the songs yourself, sing them yourself, orchestrate them yourself. I found this appealing, and I began to write songs,” he tells The Paris Review.

Ishiguro, however, had to hold his initial dreams about becoming a songwriter in abeyance and enrolled in 1979 in a creative writing course run by Malcolm Bradbury at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in Norwich, where Angela Carter was also his teacher and mentor. In 1980, when Ishiguro graduated from the course, he had already obtained an advance from Faber and Faber for a novel-in- progress.

In 1981, Ishiguro published his first short story and moved to Cardiff, Wales, and later that year, his first three short stories in a Faber anthology, Introductions 7: Stories by New Writers. In the summer of 1981, he moved to London with Lorna.

Mapping Memories

In 1982, Ishiguro published his first novel, A Pale View of Hills, the story of Etsuko, a middle-aged Japanese woman living alone in England, whose mind dwells on the recent suicide of her eldest daughter from her first marriage. In a story where past and present blend in a “haunting and sometimes macabre” way, she relives scenes of Japan’s devastation in the wake of World War II, even as she recounts the “weirdnesses and calamities” of her own life. When the novel opens, the reader is led to believe that Etsuko is coming to terms with the tragedy by recounting the story of a friend she had back in Nagasaki just after the war. The friend wants to leave Japan and move to the United States; she also has a young troubled daughter whose behaviour echoes the protagonist’s own experiences with her daughter. It’s only towards the denouement that we know about the novel’s uncanny “doppelganger dimension”. At some point of the novel, Etsuko says, “Memory, I realize, can be an unreliable thing; often it is heavily coloured by the circumstances in which one remembers, and no doubt this applies to certain of the recollections I have gathered here.”

In recent interviews, however, Ishiguro says that while he is fond of the novel, he thinks the ending is almost like “a puzzle”. He says: “I see nothing artistically to be gained by puzzling people to that extent. That was just inexperience — misjudging what is too obvious and what is subtle. Even at the time the ending felt unsatisfactory.”

A Pale View of Hills received the Winifred Holtby award of the Royal Society of Literature “for the best regional novel of the year”. The novel, in a sense, set the template for much that would follow. Of course, Ishiguro would go on to reinvent himself with every novel, but the texture of his novels — reflecting the subtle malleability of memory and identity, and the simmering tension between the two, featuring a cast of characters scanning their past for clues to their identity, loss and abandonment —was to remain the same. To read Ishiguro, therefore, is to move in a concentric circle; you keep arriving at similar destinations. And his skill lies in the fact that each time you arrive at these destinations, you seem to breathe in a new air. “I tend to write the same book over and over,” Ishiguro told The Guardian in 2015, “or at least, I take the same subject I took last time out and refine it, or do a slightly different take on it.”

Following the success of his first novel, Ishiguro was included in Granta magazine’s list of the 20 best young British novelists in 1983. Ishiguro was in august company. The other 19 writers on the list included the likes of Martin Amis, William Boyd, Salman Rushdie, Julian Barnes, Pat Barker, Ian McEwan, Shiva Naipaul, Graham Swift, Alan Judd, Philip Norman and A. N. Wilson. A year before this, Ishiguro took up British citizenship, which had been on the cards. He felt British and thought that his future was in Britain, he told Nicholas Wroe of The Guardian in 2005. In Kazuo Ishiguro, (Routledge Guides to Literature, 2010) Wai-chew Sim, professor at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, writes: “His bicultural status was presented as an epitome of British multiculturalism. His reception was hailed as a sign of a more confident and inclusive society less riven by the conservative identity politics of the preceding era….Among other things, Ishiguro strives to breach geographical and cultural boundaries that many take for granted and are having to question in an era of increased globalization and cross-cultural exchange.”

Ishiguro’s second novel, An Artist of the Floating World (1986), fleshes out a subplot in A Pale View of Hills featuring a retired teacher who has to rethink his values in the aftermath of the war. The milieu is similar: post-war Japan. The protagonist, Masuji Ono, a painter who had supported militarism in the 1930s with propaganda artwork, is forced to question the certainties of the Antebellum era, marked by the economic growth of the South based on slave-driven plantation farming. The aging artist recounts his experiences as an Imperial propagandist in pre-war Japan. As the mature Ono struggles through the devastation of that war, his memories of his youth and of the “floating world” — the nocturnal realm of pleasure, entertainment, and drink — offer him both escape and redemption, even as they punish him for betraying his early promise as an artist. Drifting in disgrace in post-war Japan, indicted by society for its defeat and reviled for his past aesthetics, he relives the passage through his personal history that makes him both a hero and a coward but, above all, a human being. The novel — its back-and-forth narration evinces Ishiguro’s ambitious attempt to capture the texture of memory — was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and won the Whitbread Book of the Year award.

At Home in the World

Ishiguro’s use of settings in his two early novels, however, led to his ethnicity being accentuated, addressed by all and sundry. In The Novels of Kazuo Ishiguro (Palgrave, Macmillan, 2010), Matthew Beedham, deputy head (Humanities) at Coventry University, writes, “Since the appearance of his earliest novels, his ethnicity has been a prominent concern, addressed in an almost standard paragraph in all reviews that notes that Ishiguro was born in Japan but raised since the age of five in England.” In an interview with Alan Vorda and Kim Herzinger, Ishiguro says that the attention he received early in his career was largely due to his ethnicity since, after Salman Rushdie won the Man Booker Prize for Midnight’s Children in 1981, the search was on for “other Rushdies”. His first novel happened to have come out at a time when there seemed to be an interest in voices like him: “I received a lot of attention… because I had this Japanese face and this Japanese name and it was what was being covered at the time”.

The overemphasis on his ethnicity and the attempts to read his novels as the work of a Japanese writer, however, is “ill-conceived”, Ishiguro has said. He maintains that the “calm surface” of his first two books was simply an expression of his “natural voice”, and that he wasn’t trying to write them in “an understated, Japanese way”.

In an interview with Dylan Otto Krider, Ishiguro said that as a novelist, he wanted to write about universal themes. “So, it always slightly annoyed me when people said, ‘Oh, how interesting it must be to be Japanese because you feel this, this, and this’, and I thought, ‘Don’t we all feel like this?”

The truth is that Ishiguro is a writer of the world: the emotional travails and perplexities of his characters — the stories of people whose past keep coming in the way of their present, often altering the understanding/memory of their own history or identity — have a universal echo. Even in novels with a decidedly Japanese setting, the story seems to be of people anywhere in the world, buffeted by recurring waves of uncomfortable memories, scarred by war or living with the burden of missteps and missed opportunities.

In fact, if there is any tradition Ishiguro’s writing is deeply steeped in, it’s not Japanese, but Western. In an interview with Gregory Mason, Ishiguro says: “I feel that I’m very much of the Western tradition. And I’m often quite amused when reviewers make a lot of my being Japanese and try to mention the two or three authors they’ve vaguely heard of.” Ishiguro has, in several interviews, mentioned Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–81), Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), Charlotte Brontë (1816–55) and Charles Dickens (1812–70) as his influences. What does Ishiguro likes about the “full-blooded nineteenth-century fiction” he first read in university? He tells Susannah Hunnewell in an interview for The Paris Review, “It’s realist in the sense that the world created in the fiction is more or less akin to the world we live in. Also, it’s work you can get lost in. There’s a confidence in narrative, which uses the traditional tools of plot and structure and character. Because I hadn’t read a lot as a child, I needed a firm foundation. Charlotte Brontë of Villette and Jane Eyre; Dostoyevsky of those four big novels; Chekhov’s short stories; Tolstoy of War and Peace. Bleak House (Charles Dickens). And at least five of the six Jane Austen novels. If you have read those, you have a very solid foundation.”

Ishiguro tells Mason that his “Japanese influences” includes Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965), Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972), Masuji Ibuse (1898–1993) and Natsume Soseki (1867-1916). He, however, adds that the most relevant Japanese influence in his work is probably the Japanese films of directors such as Yasujiro Ozu (1903-63) and Mikio Naruse (1905-69). In another interview conducted shortly after the publication of An Artist of the Floating World, Ishiguro says: “If I borrow anything from any tradition, it’s probably from that tradition that tries to avoid anything that is overtly melodramatic or plotty, that tries basically to remain within the realms of everyday experience.” He also tells Mason: “I’m very keen that whenever I portray books that are set in Japan, even if it’s not very accurately Japan, that people are seen to be just people. I ask myself the same questions about my Japanese characters that I would about English characters, when I’m asking the big questions, what’s really important to them. My experience of Japanese people in this realm is that they’re like everybody else. They’re like me, my parents. I don’t see them as people who go around slashing their stomachs.”

Therefore, any attempt to approach the work of Ishiguro, argues Wai-chew Sim, must be through an understanding of his style and his narratives rather than basing discussions of his work on his biography. While numerous critics, including Rocio Davis and Mark Wormald, have connected Ishiguro to Rushdie, Sim says it is a “superficial” connection. “My style is almost the antithesis of Rushdie or Timothy Mo. Their writing tends to have these quirks where it explodes in all kinds of directions,” Ishiguro said in an interview.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated