She’d taken the leap to follow the life of her poems. They came from anger and hissed like droplets on hot metal. The numb indifference of whiteness, its laughing, joking cruelty. The pain of blackness that she feared but wanted to love. Blackness that had touched her kindly, with a glint in its eye. Brown that belonged to her, often invisible to the world. Little slippery stories that crawled in verse, speaking in tongues. (…)

Megha cringed every time she heard her own poems performed… They sounded alien. They claimed slimy muscles she did not possess. Suffering she had not suffered. How was that possible. They were beautiful, frozen sculptures of rage in print. Why did they bleed so viciously when other people spoke them aloud?

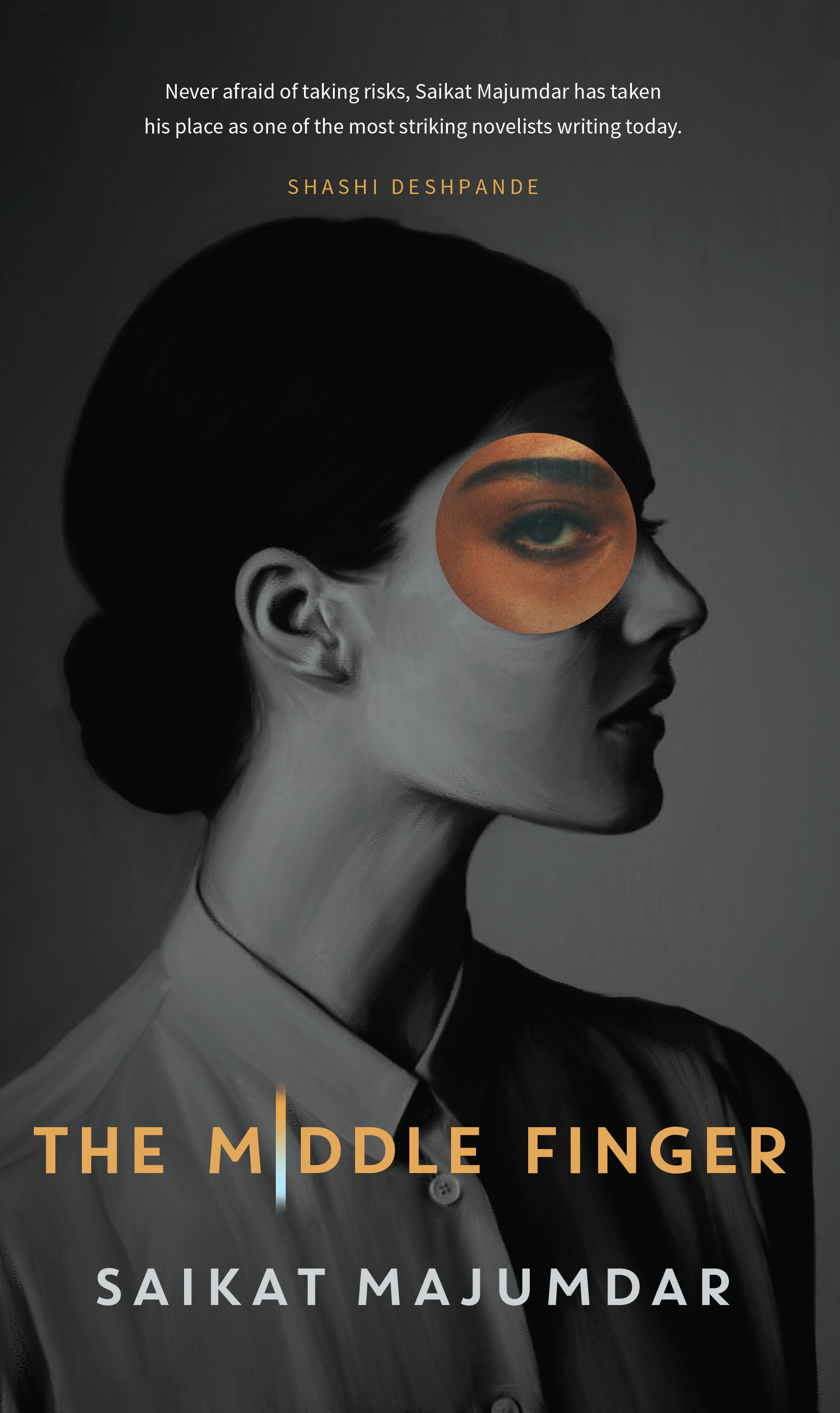

Saikat Majumdar’s The Middle Finger (Simon & Schuster India) is about social entitlement and creative ownership. It questions the age-old elite entitlement to, and appropriation of, resources that ideally should be available to all; and it raises doubts about the authenticity of the creative ownership of experience that is not one’s own. Megha, the protagonist, has to contend with both, in her twin identities as a teacher and a writer.

The initial part of the novel is taken up with Megha struggling with the question of authenticity in her poetry, but it never quite leaves her, hounding her all the way from New York to New Delhi. She has given up mid-way on a Ph.D at Princeton when we first meet her, settling for teaching freshman comp at Rutgers (which she does well) and writing poetry (which become quite a rage among her students, who perform them in pubs and upload on YouTube and Instagram). An unexpected Arts Fellowship comes as a breather from her excessive workload and an accidental meeting at a dinner party opens up an opportunity for her to return to India (temporarily, she is told) to teach at a new University, all gung ho about implementing innovative ideas in education but catering primarily to the rich and powerful.

Enter Jishnu and Poonam in her life. They are the Arjun and Eklavya, respectively, to her Drona.

In Majumdar’s adaptation of this popular story from the Mahabharata, mentorship is thus problematized not just along the lines of caste and class, but also gender. And as it happens, sexuality.

In a way, Majumdar had been gravitating towards such a story. Education — in the widest sense — has been a preoccupation with him. Apart from his career as an academic, teaching Literature and Creative Writing for a decade and a half (at Stanford and Asoka), he has been writing regularly, for several years now, on various aspects of University education for Outlook and The Times Educational Supplement. He has also written a book of non-fiction on the Indian higher education system — College: Pathways of Possibility (2018). And his novels (bildungsroman, all) have negotiated, with varying emphases, the role that educational institutions play in the formation of identity — be it the chastening routine of Christian missionary school in a disturbed childhood (The Firebird, 2015) or the awakening of sexuality in pre-pubescent boys in a monastic hostel run by Hindu monks (The Scent of God, 2019). A novel focussing on ethical questions around mentorship was thus, I feel, almost an inevitable next step in his writing trajectory.

The Middle Finger

By Saikat Majumdar

Simon & Schuster India

pp. 200, Rs 499

Megha’s relationship with her mentees begin to unfold halfway into the novel, in scenes of striking contrast: one of intellectual thrust and parry with Jishnu in a ‘Thinking to Write’ class, where he overturns her ideas of ‘focus’ in composition, following a challenging writing prompt; the other of accidental acquaintance and reluctant familiarity with Poonam in her private space, with her driver Ajmal playing the catalyst. Jishnu is more than equal to Megha in social status, being scion of an influential political family, while Poonam stands at the other end of the scale — having made precarious transitions from Ranchi to Calcutta to Delhi on the strength of the kindness of her Church. Is it possible to bridge the gulf that separates them?

She [Poonam] said each word carefully, and yet sometimes Megha could not understand what she was saying. She was not her student, she could never be. She was too far away.

Majumdar is at his best delineating the changing dynamics of this relationship, where lessons are learnt that were never taught and where prior claims to affection are contested.

The novel is a master class in fiction-writing. Everything that is considered important in it is done to perfection here — plot, character, scene, dialogue, with the old adage of “show, not tell” looming over it all. Some scenes stand out for the sheer finesse of their execution: Megha’s spat with her high school buddy, Vivek, about the validity of their respective career choices; Megha torn between trying to finish an article and warming up to Poonam’s sudden presence in her home; Poonam’s moving speech in her Church the day Megha visits her, with Jishnu and Siya in tow.

But finesse is discernible even at the micro level of narration: in descriptions (Rory turning Megha’s poems into dance); quotidian reflections (the noisiness of Indian mornings with its catalogue of domestic service-providers); not to forget the crisp sentences that stay with you: “The classes were a relief as the rush and noise gave her days of rattling confusion”.

I only wish the novel had more on two counts: I would have liked to read more poems by Megha, given that so much of the narrative is taken up with her anxiety of authenticity; and I wish the novelist had been less cautious in dramatizing desire. Saying anything more on this count would be to give away the most refreshingly radical aspect of the book.

Comments

*Comments will be moderated