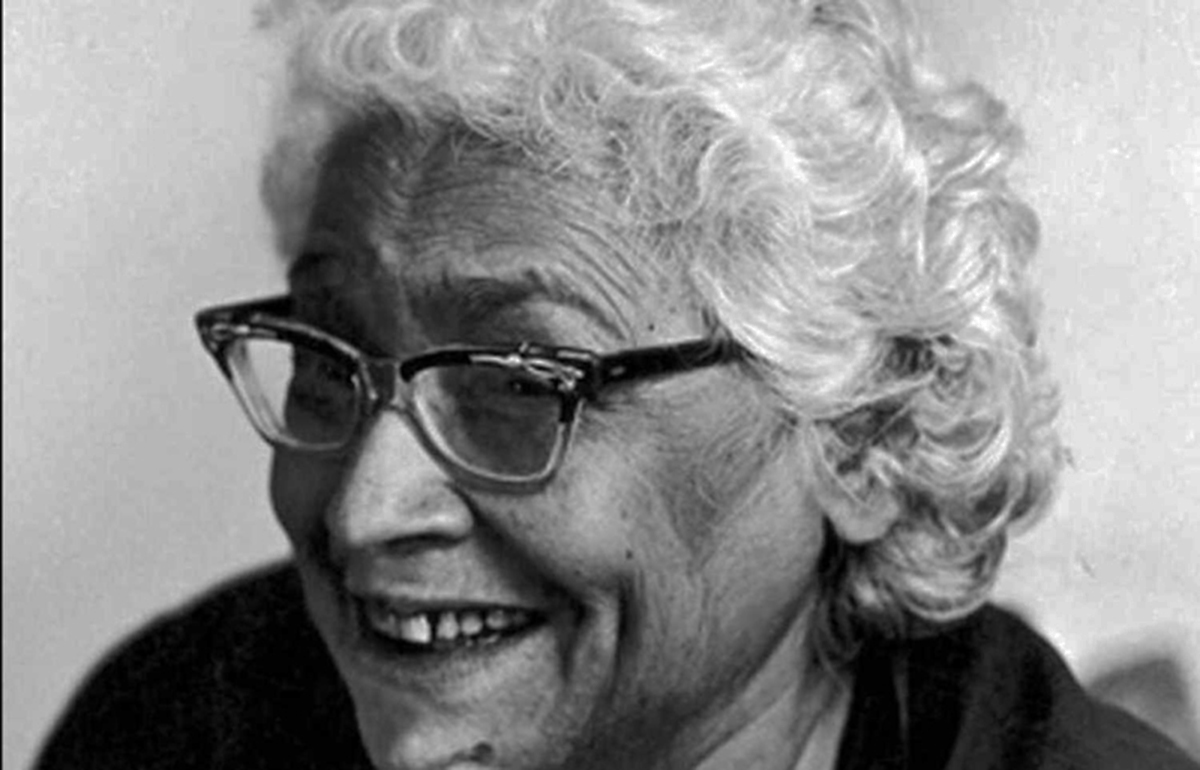

Ismat Chughtai, one of the pioneers of Urdu fiction.

Ismat Chughtai strikes right at the festering sore of the society and the deeply entrenched patriarchy

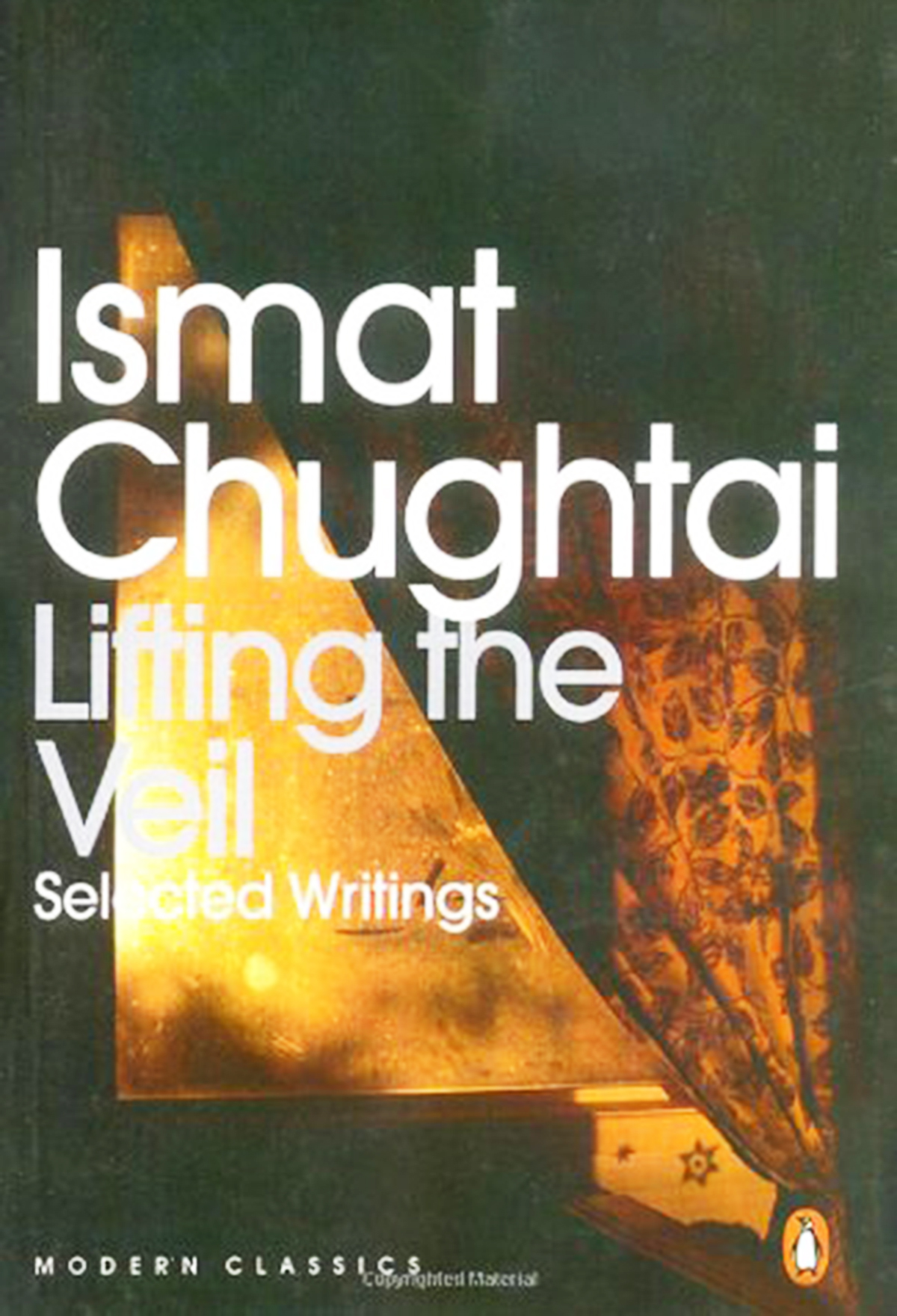

“Purdah had already been imposed on me, but my tongue was an unsheathed sword. No one could restrain it,” writes Ismat Chughtai (1915-91), one of the pioneers of Urdu fiction, in a fragment from her memoir in Lifting The Veil: Selected Writings of Ismat Chughtai (2001), selected and translated by M. Asaduddin. Just as her tongue couldn’t be restrained from speaking out her mind, undeterred by the expectations of modesty and gracefulness, so could Chughtai’s pen not be held back from writing truth to power. As the title suggests, all the short stories included in this collection do actually lift the veil from all that has hitherto been brushed under the carpet and let us have an unfiltered peek into the lives of these characters, removing the constricting gauze enforced upon them. Chughtai strikes right at the festering sore of the society — the deeply entrenched patriarchal culture. She unabashedly explores multiple feminist themes, including women’s desire and sexuality, homosexual relations and the intersectionality of oppression, by addressing caste-class aspects of gendered identity, the oppressive nature of the institution of marriage and the possibility of female friendships and solidarity. The protagonists of her stories range from an aristocratic begum “past her prime” to a young widowed maidservant getting pregnant out of wedlock, a sexually assertive woman living in a shack to a teacher who wears her chastity on her sleeve.

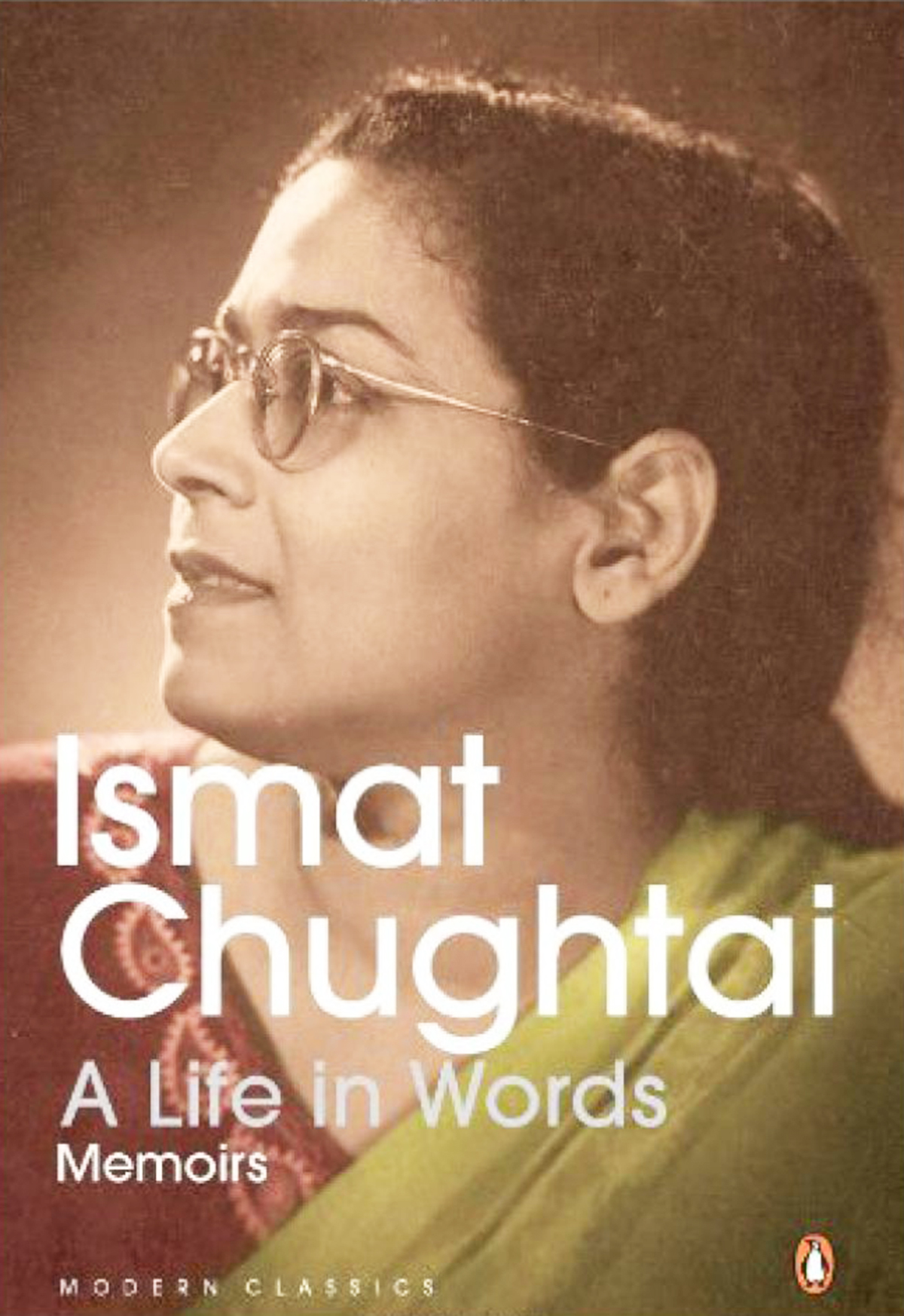

Chughtai’s compelling memoir, Kaghazi Hai Pairahan (The Robe is Made of Paper, 1979-1980) bristles with the delightful descriptions of her childhood years, the conflicted experiences of growing up in a large Muslim family during the early decades of the twentieth century, her fight to receive education and the struggle to find her own voice as a writer. Its first complete translation from Urdu was also done by Prof. Asaduddin, professor of English at Jamia Millia Islamia, and published as A Life in Words (Penguin Books, 2013). Lifting The Veil brings together Chughtai’s twenty one stories and essays written in the narrative fashion similar to that of her short stories. M. Asaduddin writes in the introduction that this collection seeks to bring to represent the multifarious nature of the literary engagement of Chughtai without confining it to her feminist concerns. While she wrote plays, novels and travelogues, Asaduddin notes that her most remarkable achievement lies in the genre of short stories. “Her sparkling dialogue, brilliant turn of phrase and scintillating humour — the essential ingredients of her style — achieve startling effects when she works on a small canvas with a few bold strikes.” He states that Chughtai is a writer in the realist tradition; wary of “the modernist artifice and the new poetics of fiction”, she prefers directness over complicated narrative devices, which allows even a novice to enjoy her stories. Appreciating the local flavour of the settings and the cultural rootedness of her characters — without which much of their charm would be lost — as integrals element of her writing, he identifies the same as a major challenge he faced while translating her works into English.

Lifting The Veil: Selected Writings of Ismat Chughtai

Selected and translated by M. Asaduddin

Penguin Books (2001)

pp. 288, Rs 350

“I had studied so much that whenever there was a debate, I would beat to pulp all the young men who were scared of the sight of books. They considered themselves superior to women merely because they were men (“In the Name of those Married Women”). Chughtai practised what she preached and didn’t shy away from calling out the double standards of the society even if it meant challenging those close to her. When a close acquaintance, Mr. Aslam, rants about the alleged obscenity in “Lihaaf” and tries to school her on what an educated girl from a decent Muslim family is supposed to write, she retorts with full force that he himself in one of his stories graphically describes a sexual act for the mere sake of titillation, to which the only explanation he can offer is that his case is different, he is a man. She attacks this hypocrisy in the story, “The Homemaker” in which Mirza falls for his domestic help Lajo and convinces her to marry him. Lajo loves being the mistress of the house, cooking, keeping it clean and ordered but she is a sexually assertive woman who detests wearing pajamas instead of her free-flowing lehenga. Imposing pajamas on her after marriage signifies the need for her sexuality to be guarded. Mirza tries to tame her into becoming a chaste wife while he himself keeps visiting prostitutes.

“I am still labelled as the writer of ‘Lihaaf’. The story brought me so much notoriety that I got sick of life. It became the proverbial stick to beat me with and whatever I wrote afterwards got crushed under its weight (“In the Name of those Married Women”). “Lihaaf” (The Quilt) undoubtedly is the most renowned work of Chughtai and rightly so; it exposed how a woman’s sexuality is suppressed in a heteronormative marriage by narrating the tragic fate of Begum Jaan who nonetheless goes on to indulge in an erotic relationship with her masseuse Rabbu, but it enters a dark territory when the sensual drive borne out of sexual neglect becomes predatory and ultimately leads to paedophilia. But the fact that an artist could be censured so much that she’s taken to court on the grounds of obscenity is telling of the extent social gatekeepers would go to in order to penalize those who refuse to conform and, most importantly, that she’s doing something right, something that otherwise wouldn’t be allowed to come to the fore. This is exemplified by the instance Chughtai recalls wherein she goes to meet the begum on whose life “Lihaaf” was based but contrary to her fears, she looks at her joyously, leaps at her and takes her into her arms.

Her writing enables the reader to enter the whirlwind going on in the character’s mind in a way that even a distant fictional character’s fears and dilemmas begin resembling such grey areas very intimately embedded in one’s own psyche, something I felt vividly while reading the story, “Vocation”. It chronicles the tale of a teacher who has internalised the patriarchal notion that chastity is a woman’s most precious virtue and bitterly looks down upon courtesans and prostitutes, she likens the struggle of virtuous women like her against prostitutes with that of the workers against capitalists and is proud of her “noble” profession. But when the family living in the apartment next to her (who she believes are prostitutes) try to strike friendship with her, she begins slipping into an existential crisis. She despises prostitutes so greatly that whenever a rational and humane thought regarding them crosses her mind, she begins questioning her own sanity. She knows that one of her uncles used to squander lavishly on prostitutes, she realises that she sells her brain while the prostitute her body, that both are selling something of theirs in order to ascend in their respective professions but such thoughts make it further difficult for her to cope with the binaries of good and evil she has constructed for herself. The ensuing delirium doesn’t let her perform even the most mundane chores without getting dazed, only to be thunderstruck later by the revelation that her neighbours are a reputed aristocratic family.

In the chapter “My Friend, My Enemy”, she recounts her relationship with Saadat Hasan Manto, which indeed is a unique one. While Chughtai is done great disservice by being labelled as “female Manto”, it is worth exploring the friendship between two eminent contemporary authors writing during the most tumultuous times of the subcontinent, also because there’s an inherent tendency to sexualize friendships between men and women. Both argued and debated vociferously with each other and disagreed on a number of issues ranging from love to each other’s masterpieces but had deep admiration as well. “After meeting Rafiq I realised how deep was Manto’s study of his character……He could track down pearls among the socially discarded, and in dirt.” She marvelled at him being specialised in childcare but also called him out when he scoffed at “the small talk of illiterate and stupid women of mohalla” or exclaimed that a woman must be embarrassed at listening to vulgar words. He fiercely supported her in her decision of not apologising for writing “Lihaaf” and retorted remarkably that “a woman’s chest must be called breasts and not groundnuts” when the opposition lawyer charged that the term chest was obscene in the aforementioned story. Chughtai also defended him brilliantly in front of others, especially the instance when the judge says Manto’s writings are littered with filth to which she responds that the world is also littered with filth. “I am fortunate that I have been appreciated in my lifetime. Manto was driven mad to the extent that he became a wreck”, she writes in the chapter “In the Name of those Married Woman”.

The very first story in the collection, titled “Gainda”, intertwines the pressing issues of child marriage, early widowhood and the rigorous social norms henceforth imposed upon young girls, violent ill treatment of domestic helps, love transcending the boundaries of caste and class, stigma associated with premarital sex and the precarious fate of an “illegitimate child” and his mother. While a second reading could draw me to tears, the element which touched my heart the most was the celebration of female friendships which traverse from childhood innocence, playful fights and jealousies to complicated territories of understanding and solidarity. “ ‘Gainda’ peered into my eyes searching for something. She seemed reassured; as though she had found whatever she was looking for. She effortlessly lifted the baby and put him in my arms (attribute as above).” It affirms the feminist idea of female friendship and sisterhood having huge potential for solidarity, how this can be harnessed to forge collective resistance is the question of utmost importance since women have relatively lesser freedom and spaces to create such bonds, a lot of which is delegitimised by being dismissed as gossip chambers. It also reminded me of The Bluest Eye by Toni Morison (1970), especially if one relates how the narrator finds Lajo’s son beautiful when everyone else curses and wishes him to die with the instance wherein Mac Teer sisters sacrifice their savings and plant marigolds so that Pecola’s child could survive when everyone else wishes the opposite.

Chughtai questioned the social mores of her time without mincing words, she revelled in transgressing boundaries and it is perhaps here that her resounding significance lay. She was far too ahead of her times and is still no less relevant; she is the feminist icon we need.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated