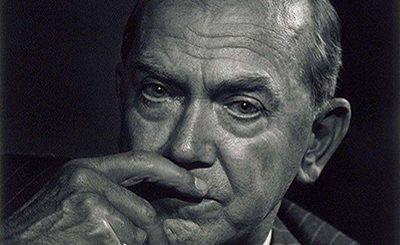

Author and Man Booker Prize juror Sarah Hall at the announcement of the 2017 shortlist. Photo courtesy Man Booker Prize

Novelist and poet Sarah Hall was shortlisted for the 2004 Man Booker Prize for her critically acclaimed second novel, The Electric Michelangelo, the biography of a fictional tattoo artist, set in early twentieth century Morecambe Bay and Coney Island. Her 2009 novel How to Paint a Dead Man — a fierce and brilliant study of art and its place in our lives which weaves together multiple lives through the prism of a still life painting — was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. It moves from Italy to England, spanning nearly half a century, and brings together the lives of four disparate characters.

Her debut novel, Haweswater (2002), is a rural tragedy about the disintegration of a community of Cumbrian hill-farmers, due to the building of a reservoir. It won the 2003 Commonwealth Writers' Prize (Overall Winner, Best First Book). Her third novel, The Carhullan Army (2007), a science fiction, won the 2007 John Llewellyn Rhys Prize and James Tiptree, Jr. Award, and was shortlisted for the 2008 Arthur C. Clarke Award. In America, the novel was published under the title Daughters of the North.

In 2013, Hall was included in the Granta list of 20 best young writers.

In an interview with The Punch, Hall says that great fiction moves beyond borders and that’s what the Man Booker Prize — which is now open to any novel written in English and published in Britain, regardless of the author’s nationality, rather than being restricted it to writers from Britain, Ireland, Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth — showcases. ”Novels are so wonderfully varied. I think what is often written about in relation to prize decisions is wrong and superficial, an exterior perspective that can’t possibly know the workings of a judging panel. The shortlist meeting took 8 hours, nearly, and each book was thoroughly assessed and discussed. Each book, and how it relates to us, the world, the history of the novel. The authors were not discussed. In any case, trying to define an author is a million times harder than trying to define a novel — that would be utterly foolish,” she says.

Besides Hall, the panel of judges includes Baroness Lola Young, who chairs the jury, Lila Azam Zanganeh, Colin Thubron and Tom Phillips.

The shortlisted novels are:

1. 4321 by Paul Auster (USA), published by Faber & Faber

2. History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund (USA), published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

3. Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (UK-Pakistan), published by Hamish Hamilton

4. Elmet by Fiona Mozley (UK), published by JM Originals

5. Lincoln in the Bardo, George Saunders (USA), published by Bloomsbury Publishing

6. Autumn by Ali Smith (UK), published by Hamish Hamilton

Hall says that fiction helps us understand ourselves and others better. “We tell stories to learn and survive and develop,” she says.

Excerpts from an interview:

Nawaid Anjum: How was the process of selecting the longlist, out of the 145 novels submitted this year, for you?

Sarah Hall: It was exhausting, naturally, and required huge focus. But the very best literature rose to the top of the pile quite easily and the judges were in agreement.

Nawaid Anjum: Three notable novels, which were on the 13-book longlist — Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness and Zadie Smith’s Swing Time — could not make the cut for the shortlist. As a novelist analysing their works, how would you see their latest offerings?

Sarah Hall: I’m afraid I can’t comment on the books from the longlist and why they did not make the shortlist. The longlist was enormously strong and all those left off the shortlist were notable. All thirteen books were examined rigorously, among other things for technique, technical achievement and problems, scope, ambition, execution of ideas, recalibration of research into fiction, artfulness, innovation, sensibility, style, intelligence, landscape, character development and dynamics, psychology, interiority, how all these things combine, memorability, and of course, X factor.

Nawaid Anjum: What worked for the six novels on the shortlist? As a member of the jury, what did you set out to look out for in the qualifying novels?

Sarah Hall: There was no set of absolute standards — but aspects of the above were examined — as well as any idiosyncratic contextual prospect a novel itself might bring up. The prize is seeking the best work of fiction in a given year. Novels are so wonderfully varied. I think what is often written about in relation to prize decisions is wrong and superficial, an exterior perspective that can’t possibly know the workings of a judging panel. The shortlist meeting took 8 hours, nearly, and each book was thoroughly assessed and discussed. Each book, and how it relates to us, the world, the history of the novel. The authors were not discussed. In any case, trying to define an author is a million times harder than trying to define a novel — that would be utterly foolish.

Nawaid Anjum: Half of the writers on the shortlist this year are from America — Paul Auster, Emily Fridlund and George Saunders. In certain quarters, this has revived anxieties about the 2013 decision to open the prize to any novel written in English and published in Britain, regardless of the author’s nationality, rather than restricting it to writers from Britain, Ireland, Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth. How would you respond to

such anxieties?

Sarah Hall: I would not have agreed to judge the prize if I had any anxieties about its remit. I think that’s an old story now. Let’s see how the prize develops going forward. Great fiction moves beyond borders — that’s what this prize showcases.

Nawaid Anjum: Could you tell us about your appreciation of the form of novel? Who are some of the greatest novelists, both past and present, you have admired?

Sarah Hall: Where do I start? I try to read as much contemporary fiction as possible — I think the novel, the best novels, have become exceptional, psychologically astute, transportive, politically challenging, as well as entertaining. They have always been like that perhaps, across the ages, but I’m interested to see the modern adaptations.

Nawaid Anjum: In our troubled and fractured times, what role do you think fiction can play in bringing individuals, nations and societies together?

Sarah Hall: They are humane and companionable, and help us understand ourselves and others better. We tell stories to learn and survive and develop.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated