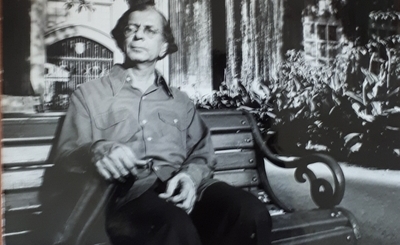

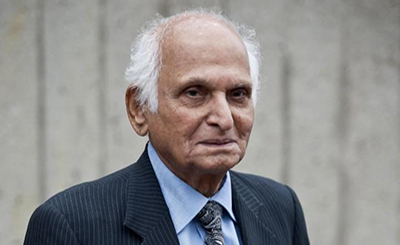

Intizar Husain (1925-2016), considered to be one of the most significant fiction writers in Urdu of the 20th century, passed away on February 3 last year. Born in Dibai, Bulandshahr, in British-administered India, he migrated to Pakistan in 1947 and lived in Lahore. He was the author of three novels. Basti (Settlement) is a beautifully-written reckoning with the tragic history of Pakistan. The novel begins with a mythic, even mystic, vision of harmony between old and young, man and woman, Muslim and Hindu. Then Zakir, the hero, wakes to the modern world. Crowds gather. Slogans echo. Cities burn. Whether hunkered down with family or furtively meeting to exchange news with friends in cafés, Zakir is alone in a country lost to the politics of loneliness. Naya Ghar (The New House) paints a picture of Pakistan during the ten-year dictatorship of the Islamic fundamentalist General Zia-ul-Haq. Agay Samandar Hai (Ahead Lies the Sea) juxtaposes the spiraling urban violence of contemporary Karachi with a vision of the lost Islamic realm of al-Andalus.

Mahmood Farooqui's A Requiem for Pakistan: The World of Intizar Husain, published by Yoda Press in 2016, is a "personal homage to one of the greatest and one of the most sagacious writers that the subcontinent has produced in the last 100 years".

An excerpt:

Returning to Dibai is a kind of homecoming for Intizar Husain (IH). For me, writing about Dibai today is a return to my childhood. For in writing about his Dibai I am also writing about my Gorakhpur and our Padrauna and our Badaun and our Banaras. Indeed, the Qasba life that Dibai represents did not overnight vanish with the formation of Pakistan. It continued long into the twentieth century and in some places it lives on still. There is still sharing, there is still harmony, and childhood represents the same wonders to people from different classes and religions and caste backgrounds who live in these proto-urban places1. Residents of these Qasbas took an inordinate pride in them. Many would suffix the names of these places to their own names. Hence we had poets and artists like Josh Malihabadi, Jigar Muradabadi, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Kaifi Azmi, Kamal Amrohvi. Muharram, Dussehra and Holi are still the biggest festivals of many qasbas which are also the sites of what is called a juloos. A juloos means a public procession and it provides us with continuities between our long medieval public culture and our shorter modern politics. Emperors went out on a juloos on special occasions, infamous prisoners and Imperial dissidents (and dissenters) were paraded in a juloos, Holi and Muharram invited a juloos, the Congress party periodically took out a juloos during the national movement, the Communist party took out a juloos of its workers, the Gurus’ birthdays invited julooses from our Sikh brethren — the juloos remains an undertheorised and understudied feature of our public culture. Sandria Freitag’s study of communal relations in Bareli over a few decades in the nineteenth century gives primacy to the route of the juloos and contestations over it, which congealed over time2. Colonial administrators and Indian District Magistrates following them have spent endless hours, sometimes days, negotiating the paths of these public julooses. But there was more to Dibai than mere julooses; here are some snippets in IH’s words and some in my paraphrasing3:

Snakes abounded. Muslims had no compunction in killing them. Hindus were much more compassionate towards them. Aiyya amma used to tell us stories about the King of Snakes, Basath in her telling, who resided in the nether world, the paataal. She also used to point to the dark and mysterious kothri where apparently a fierce snake resided but she would never name him because he was wary of being named. [Now] if I could I would tell Aiya Amma that this king of paataal was not Raja Basath but Raja Basik (Vasuki), the brother of Sheshnag. Prajapati’s daughter Kadru had bred a thousand cobras of which these two were the only good ones.That is why I felt that the kothriwala must have been a progeny of one of these brothers because it never bit anyone. Anyway Aiyya Amma maintained that it was sitting over a great horde of asharfis which somebody had buried there during the great ghadar of 1857 and she could hear it hiss, saying ‘sacrifice a son, take the treasure’.

The story would have died but after the whole family had moved to Pakistan, one of IH’s aunts said with great pique that the house was bought by a local Lala and when digging was underway to lay the foundations for a new house, guess what he found? Bricks of gold! So it was true, that story was true. But the story is not over yet. When IH finally returned to Dibai, for the first time (he was to visit it a few more times at the fag end of his life) he was informed by a relative who accompanied him, ‘The relative’s house you are looking for was bought by a Lala. A treasure was found buried in it.’ Then,’ he sighed deeply and said, ‘we heard that a person in the prime of youth died in that house.’

May god grant heaven to Aiyya Amma at every turn she makes in her grave.

So man was not the only creature which inhabited those houses in Dibai. There were animals and of course, djinns and ghosts and messengers of the devil. IH’s house lay at the far end of the Muslim mohalla, adjoining the Hindu houses.

Our house was steeped in Islamic atmosphere but the atmosphere around was steeped in Hindu color. If you walked four steps ahead you found a mandir, if you went six steps back you found a masjid. So I would dash across roofs which lay between the mandir and the masjid, roofs which belonged to both Hindu and Muslim houses chasing after a floating kite which would forever elude me…. A little ahead of our house lay the bazaar, there were spots there where the harmonium was played. Maybe it was one of these groups which would do the Ramlila right next to our house. So I didn’t need to step out of the house. Sitting on the parapets of my house, I saw many Ramlilas.

Holi and Nauroz follow close on each other’s heels. If Holi is a festival of colour, Nauroz too is a festival of colour.

On Nauroz my father would take out a narsal, a reed pen, sprinkle saffron in a flower pot and then write charms, taviz, after the rose leaves floating in a pan had automatically start circling fast. Father would also do something similar everytime a new moon was coming. He would go to the terrace, accompanied by a pot of water, sometimes a mirror, sometimes a green twig. Who knew what this new moon would demand you to see after you sighted it. Whenever there was a lunar eclipse he would spend hours in prayer so that no harm would come to the moon.

And what are the shooting stars? What they are is this, whenever the Shaitan, Satan, ties to trespass among the angels in order to overhear the instructions being given to them by Allah and the angels on watch discover this, they strike him with their mace. So when you see a shooting star know that an angel has just struck the Shaitan on the head.

IH continues:

So these were the wonders of our house. You hardly needed to step out. The main door opened on the street, on the right and left lay two big elevated stone platforms. Standing on the threshold or sitting on these platforms I have seen innumerable tamashas [a cognate word to Juloos]. After all, it was a part of the bazaar, there was always something happening here. There were events of many hues. It might be the Ramlila Juloos, it might be the Congress juloos, it might be the Holi juloos of holiyars, the spectacle of Holika burning. Then there were animal performers, the Bhaluwala, the bear-tamer. In addition there are hawkers, the pheriwallas, shahtoot seller, falsa seller, bangle seller and of course the bioscopeman: watch the Taj Bibi ka Rauza,watch Madina, watch the Bombay Bazar…

Floating amidst this cacophony, the voices of the Nationalist processions: ‘khadi clad, Motilal Nehru Zindabad, Sardar Patel Zindabad, Dr Kitchlew Zindabad, and now everybody together say, Mahatma Gandhi ki jai.’ Notice, no Bhagat Singh, no Pandit Nehru, no Subhash Chandra Bose and no Muslim League slogans, and take a pause to remember that Dr Kitchlew, the hero of Amritsar after Jallianwala Bagh died as late as 1963 — I mean where was he all for those years and what did he do?

And then of course there was Muharram. It is a festival of mourning and lamentation but very often the mourning becomes ostentatious and during the public juloos, spectacular. Mourners might beat themselves with chains or walk on burning charcoals. All this in order to relive the pain and torment suffered by the sons of Ali, Hasan and Husain, and their family, during the battle of Karbala. There is the performance of mourning and there is also the performance of poetry and prose of very different kinds,the majlis. IH remembers:

I had my first lesson in poetry in this very Azakhana, the mourning house. So many of the genres of our poetry have emerged from this ritual of lamentation, including Rubai, quatrains, Qita and Salam. And one had to assiduously learn the etiquette and decorum at these public gatherings of lamentation. You were not supposed to start wailing in your grief for Hasan, Husain (the grandsons of the Prophet, and their family when they faced their tribulation in Karbala in the seventh century) just like that. There was a protocol to do that otherwise you would have faced the same fate as Ismat Chughtai did when she went for her first Majlis and started wailing at the description of an arrow piercing the throat of the infant Ali Asghar. Her brothers ragged her endlessly after that, for years. No, there is an entire cultuure and protocol of lamentation. The Zakir, the speaker, takes you through many ups and downs before gently hinting that now you may start your wailing, slowly at first, taking a cue from a Buzurg. In the Imambara where Asghar Sahib used to recite the the Marsia there it was known that the first person to break into a wail would be [the Hindu] Kunwarji, and that would provide a cue to the rest.

Muharram was followed by the month of Rabi ul Awwal, the month of the Prophet’s birthday, which fell on the twelfth of that month and was hence known as Barawafat, which was a home grown name for the festival.

Ya Nabi Salam Alaika

Ya Rasul Salam Alaika

Salutation the the Prophet

Salutations to the Messenger

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated