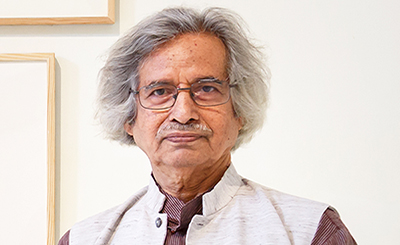

Sundaram Tagore, art historian, gallerist and an award-winning filmmaker. Photos courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery

Sundaram Tagore, a descendant of poet and Nobel Prize-winner Rabindranath Tagore, is a Calcutta-born, Oxford-educated art historian, gallerist, and an award-winning filmmaker. Born in India in 1961, he grew up travelling between Calcutta, New Delhi and the Himalayas.

Son of Subho Tagore, one of India’s first modernist painters, a poet and a magazine publisher, Sundaram grew up in an atmosphere of thinkers, writers and artists. Tagore completed his undergraduate and graduate degrees in the United States and pursued a D.Phil. in modern history at the University of Oxford. His academic pursuits — focusing on Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan, American architect Louis Kahn’s work in Bangladesh, and Indian artists’ response to European modernism — cemented his passion for cross-cultural exchange and it was in this spirit that he opened his galleries.

His efforts to engage others in the exchange of ideas through aesthetic means are driven by a passion for cultural dialogue and service. He promotes East-West dialogue through his contributions to numerous exhibitions as well as his four art galleries and their multicultural and multidisciplinary events.

Tagore’s debut film, The Poetics of Color: Natvar Bhavsar, An Artist’s Journey, premiered at the Mahindra Indo-American Arts Council (MIAAC) Film Festival in New York City in 2010 and garnered several festival awards, including The Accolade, The Indie Fest, and the esteemed Singaporean National Critics Choice Readers Award for Best New Art Film Epic Documentary of the Year and Best New Director (2012).

Tagore’s second film, Tiger City is a feature-length documentary on the world-renowned American architect Louis I. Kahn. Tagore’s inspiration for Louis Kahn came when in 1985, Tagore was given a scholarship to go to Bangladesh to study the buildings designed by Kahn. On that trip, he visited Kahn’s famous parliamentary complex Sher-e-Bangla Nagor, also known as the Tiger City.

The complex looked futuristic and ancient at the same time. In order to make this feature-length documentary film, he went on a worldwide quest to more than 14 countries to find out how this Estonian-born American architect built such a daringly modern and monumental complex in a culturally rich but economically shattered country. Excerpts from an interview with Sundaram Tagore:

Uma Prakash: Your first film, The Poetics of Color, was a documentary on an artist Natvar Bhavsar. How come you chose to do a film on an architect?

Sundaram Tagore: In the post-modern context, there isn’t really a distinction between art and architecture any longer. Architects and designers, if they are dealing with form, color and light, are essentially dealing with the same components that artists work with.

What distinguishes Louis Kahn, and the reason he is such a compelling subject, is that he transcended the functional aspect of architecture and worked in the sphere of art. For me, this movie is about the art of architecture, and that’s what fascinates me and drew me to the idea of doing a film on Louis Kahn. He may have used brick and mortar instead of paint and canvas, but he is creating art, both philosophically and in terms of design and execution. This is an art film.

Uma Prakash: What fascinated you most about Louis Kahn?

Sundaram Tagore: Kahn was a complex and sometimes controversial figure, but he was inarguably an artist par excellence because he dedicated his life to creating great works of art using architecture as a vehicle. He has created some of the greatest architecture of the 20th century, including the Salk Institute in California, the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, and his magnum opus, the Parliamentary Complex in Bangladesh.

Kahn understood the fundamentals of classical Greek, Roman and Mughal architecture. His approach was to deconstruct this architectural masonry of great weight and mass to bring light into the interior spaces. He wanted to create architecture of great beauty that would lift you up and transport you to another place.

For example, with the Parliamentary Complex, Kahn devoted a very significant amount of the space to pure aesthetic purpose, for sheer beauty over functionality to create a space that feels as if you are walking through a cathedral — the emphasis is not on the amount of space, but rather the way in which light is used in that space, how it projects a sense of immensity and lifts you up. That’s what Kahn did; he built structures that trigger an emotional response that transport you to another universe.

Sundaram Tagore promotes East-West dialogue through his contributions to numerous exhibitions as well as his four art galleries and their multicultural and multidisciplinary events.

Uma Prakash: You have used music most dramatically in the film, specially the first time you enter the Assembly Complex. What kind of research went into that and in making the film?

Sundaram Tagore: I had a long conversation with Samrat Chakrabarti, who created the music for this film, as well as my previous film, The Poetics of Color. Like me, Samrat comes from a cross-cultural background; he started out in India and grew up in England and America. He understands the confluence of cultures — and that’s the kind of music I needed. He understood what I wanted for this film and was able to produce a beautiful and affecting score.

Uma Prakash: What do you think Kahn was trying to convey when he included a mosque in the complex?

Sundaram Tagore: For Kahn, a Jew born in Estonia and raised in Philadelphia, architecture was his religion; he lived and died for it. Kahn was commissioned by an Islamic country — what was then Pakistan, and later Bangladesh — and knew he needed to contextualize his work — because unlike in the West, a Parliament doesn’t exist in a vacuum. He knew he needed to spiritualize the space. Kahn thought a lot about this and decided to build a mosque that people had to pass through to get to the assembly chamber. He believed this would lend a spiritual presence to the space and in theory this would prohibit the building’s occupants from doing anything that was unjust or not in the spirit of the greater good (he actually fell out bed when he first had this realization). That’s what gives the power to that space. He created a mosque that is not only avant-garde, but very moving and ties the whole place together.

Uma Prakash: Do you think Kahn believed in the power of light and created a structure that filtered light through different openings?

Sundaram Tagore: One of the most important aspects of Louis Kahn as an architect is that he understood light and how it penetrates a space and the ways in which it can make you flow through a space. To him, light was a spiritual element, something he learned from classical Roman architecture. He believed it spiritualized a building. It was very important to convey this idea in the film.

Tagore’s second film, Tiger City, is a feature-length documentary on the world-renowned American architect Louis I. Kahn.

Uma Prakash: You seem to like to explore a dialogue between different cultures.

Sundaram Tagore: I’m drawn to ideas of confluence of cultures, perhaps because I have lived that kind of life. When I was working on my previous film about the artist Natvar Bhavsar, an artist who had come from a small village in India and moved to New York, the epicenter of the art world, that was the same kind of idea of intercultural dialogue. Louis Kahn’s work in India and Bangladesh was the reverse journey and it was very appealing to me to explore that.

Uma Prakash: Which present day architects are inspired by Louis Kahn?

Sundram Tagore: Among the second generation of master builders —meaning those who followed the first generation of modern masters Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe — Kahn is arguably the figure who has the largest impact in terms of world architecture. Among those who followed him, Moshe Safdie, Renzo Piano, Robert Stern and Steven Holl come to mind — they all worked with him in some capacity or were deeply inspired by him. They understood the philosophical basis of Kahn’s architecture. Tadao Ando, as another example, takes light and dissolves matter through an understanding of Kahn’s process, and he is able to elevate the nature of a building and create transformational spaces in the same way Kahn could.

Uma Prakash: Are you planning to make more films?

Sundaram Tagore: Of course, but let’s see how this one goes before I make any commitments!

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

.jpg)