Jitish Kallat is at the forefront of India’s contemporary art movement. His oeuvre inquires into some of the essential ideas of life.

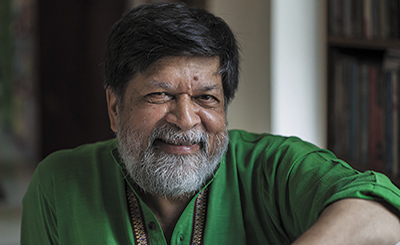

Mumbai-based artist Jitish Kallat, 43, is at the forefront of India’s contemporary art movement and his works constantly amaze the senses and challenge the mind. He was the artistic director of the second edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2014. The recent mid-career retrospective of Kallat, ‘Here After Here’ at the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi (curated by Catherine David), endorses the significance of this young artist in the Indian contemporary art world.

The mid-career retrospective is not only a show of art, but it is also a remarkable expression of an artist’s complex engagement with his creativity. The struggle to make art that speaks beyond self to an international audience is evident in several of his 100 works. They encompass a time frame of over 25 years, exploring his artistic vision sans a chronological exhibition design. By juxtaposing his works from different periods, Kallat allows them to pursue a dialogue with each other.

Jitish Kallat was born in Mumbai in 1974, the city where he continues to live and work. Kallat’s vast oeuvre — spanning painting, photography, drawing, video and sculptural installations — reveals a mind that constantly inquires into some of the essential ideas of our life. His works move from social issues to the cosmic world. While some works tackle the present situations, the others bring alive the past and show their implication in today’s world through their famous words. Kallat joined Sir JJ School of Art and later created his own visual language: one that was his own yet universal, representing contemporary life and his own consciousness.

He was first spotted at Jehangir Art Gallery’s ‘Monsoon Show’ when he was just 21. At 23, Kallat delivered his first solo, titled “P.T.O.” at Chemould Prescott Road Gallery in Mumbai. Even at that young age he had the confidence to create a large, bold painting with a figure of himself, with a watch in his mouth. His unique journey had only just begun...

Kallat’s creativity knows no bounds and he is comfortable in using a range of mediums. With great ease Kallat’s concepts and ideas are fashioned into paintings, digital photography, sculpture, videos and installations. He deals with the common and celestial with the same panache. Kallat has a thoroughly intelligent and perspicacious look at what is happening in the society. The mayhem of the Gujarat riots greatly impacted the artist. The outcome was one of his better-known works Autosaurus Tripous: skeletal remains of a vehicle burnt during the 2002 Gujarat riots. The life-size replicas, rendered as prehistoric vertebrates, are based on Kallat’s drawings of the riots and the depiction is symbolic of the chaos.

In contrast to this violence in the streets, Kallat shows the peace that India’s founding fathers sought for the nation, through yet another well-known trilogy: Public Notice. The first installation was created in 2003. With burnt text on mirror and rubber adhesive, the artist rewrote Jawaharlal Nehru’s emotional speech “Tryst with Destiny”.This was the famous speech made by India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru before the stroke of midnight on August 14, 1947, to celebrate India’s Independence against the British. This historic address reflected the emotions of the entire nation. It referred to India’s awakening into freedom after centuries of colonialism. But Kallat feels we did not live up to the promises we made to ourselves when we acquired our Independence. Kallat rewrote the iconic text using rubber adhesive on five large acrylic mirrors before setting them aflame, thereby burning the words and producing confused reflections. The viewers see distorted reflections of themselves as they look into the mirror, endorsing their chaotic state of affairs politically and otherwise.

In Public Notice 2 (2007), he re-invoked the momentous speech delivered by Mahatma Gandhi on the eve of Dandi March. Constructed from over 4,500 bone-shaped alphabets, each letter appeared as a lost relic. This vast piece of work displays important show of letters formed out of 4,479 pieces of fibreglass bones installed on shelves against a background of drenched turmeric yellow. The artist has reproduced the 1,000-word speech given by Mahatma Gandhi on March 11, 1930 at the Sabarmati Ashram by the banks of the River Sabarmati in Ahmedabad. The next day, Gandhi, along with 78 of his followers, began the historic Dandi March to protest against the British-imposed tax on salt during which the virtues of non-violence were repeatedly asserted by Gandhi. This act of non-violence is relevant and needed in today’s violent world. Kallat ingeniously places the historical text in the present context.

In The Public Notice 3 (2010), the artist draws direct parallels between the past and the present at the Art Institute of Chicago. Deftly the artist links two entirely opposite events in history that fell on the same date, although 108 years apart. They are the First World Parliament of Religions held on September 11, 1893, and the terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. Kallat uses the staircase of the art institute to project Vivekananda’s speech in the Parliament. This is done on LED displays in colours used by the colour-coded threat alert system of the Department of Homeland Security; this was his first major exhibition in an American museum. In 2010, the artist installed his large-scale site-specific LED installation, Public Notice 3, at the Art Institute of Chicago. The artwork draws on Swami Vivekananda’s haunting words calling for universal toleration and the end of bigotry and religious fanaticism.

The most inspired piece is the installation and video, titled Covering Letter. Here is a letter written in 1939 by Mahatma Gandhi to Adolf Hitler weeks before the start of World War II, making a plea for peace. The artist projects the letter in a very unusual manner. The viewer enters a dark room, smoke is cascading down, creating a smoke screen in the horizon and unexpectedly he sees this letter superimposed on the smoke screen. He is allowed to walk through the smoke screen, go to the other side and come back. This interactive piece allows the viewer to absorb the essence of the letter that was never mailed, as the British government held it back. It now hangs in Gandhi museum in Mumbai. Kallat uses light sound and a video to skillfully draw the viewer into his creation. It is like an illusion that instills excitement when viewing: A letter from a great believer of peace to possibly one of the most violent individuals that ever lived. Even today, this message from the past holds a great meaning. It is one that lives disconcertingly in the mind’s eye.

Autosaurus Tripous. Photo: The Punch

Kallat’s experiments in art are several and there is a profound level of abstraction in his work like in Wind Study. Here, the artist employs burnt adhesive and graphite on archival papers. The process is fascinating as he relies on nature to develop his vision.

He first makes a set of lines on the paper that he lays under a tree. He then decides on which lines to burn. Finally, he leaves it to the wind to decide both the direction and intensity of the marks left by the line. “I feel I submit these graphite lines, initially laid flat, to natural forces at the moment of incineration, the moment when that line is set aflame and begins its conversation with the wind. The bunt line becomes a transcript of what transpires between wind and fire in the life-duration of that line,” Kallat said in his interview with Homi Bhabha, which first appeared in The Infinite Episode, published by Gallerie Daniel Templon.

Another interesting work is Sightings D23M6Y2016 which consists of seven-part lenticular photo piece. There are seven close details of surfaces of fruits. “This feeling has been in my mind for a while; and every time I look closely at the surface of a fruit it was as if I was seeing a photographic image of the universe with distant supernova explosion and dispersed constellations manifested on its skin,” Kallat said in that interview with Homi Bhabha.

As one of the most outstanding Indian artists Jitish Kallat speaks to a world seemingly in the throes of constant change. Kallat’s paintings reflect his interpretation of modern India. Kallat captures the sense of energy, of the cacophonic hustle and bustle of Mumbai streets in a painting titled Rickshawpolis. Motorcars, ambulances, scooters, cat’s cows and humans collide on the roads of this great city with cycles, bullock carts and people. An image of Lord Ganesha, greatly worshipped in this city, joins the hustle and bustle.

Furthermore, his attraction to photography was inspired not by fantasy but by the thrill of the real world. In his series of photographs titled 365 Lives, what appears to be splashes of colour from afar turn out to be images of cars involved in accidents. These are magnified assortments of hollows, bumps and scratches on the bodies of automobiles. Here, the artist also explores the sentiments of Indian middle class mobility that feel the necessity of acquiring automobiles that alas come with their own baggage of road rage!

Yet another street scene from his city, Mumbai, is seen in Artist Making a Local Call (2005) — a monumental, panoramic photograph of the artist making a phone call from a public phone booth in a relatively busy street. The phone booth also serves as a small electrical shop and a paan (betel nut shop) at the same time; although the scene looks peaceful, there is a deceptive taxi-autorickshaw collision marked by the artist with red brackets.

Kallat’s most ambitious sculptural piece is Eight Forty Seven. This large sculptural work occupies almost 500 square feet of floor space and is made up of 14 half-built flyovers arranged such that they form the figures ‘8:47’, a frozen moment in time. Thousands of tiny toy-cars, buses, trucks and other images such as fallen trees, a deity carried on religious processions, cows, dogs etc. were cast in wax, melted down and then re-cast in translucent resin. Visually, the work has fragility of wax; the melting at once evokes chaos, catastrophe, violence, floods and a multitude of images one associates with the Indian street.

From the chaos and anguish of the bustling city of Mumbai to the cosmic world, Kallat has been an astute and artistic observer like in Epilogue. The artist takes the viewer through a celestial journey where he is surrounded with lunar landscapes. The 753-part photographic work is actually a dedication to his father. The phases of the moon are represented through rotis that his father ate during his lifetime, from 1936 to 1998. The installation comprises 22,500 such roti-moons. What is interesting is that all the frames are different and the last frame has just one moon, symbolising his father’s death. This was a deeply personal work for Kallat — an ode to his late father through a series of photographs of progressively eaten rotis. Each roti stood for the number of moons that his father had seen in his lifetime. The work had deep emotional resonance.

Jitish Kallat in his studio. Photo courtesy: Nature Morte Gallery, New Delhi

Kallat’s protagonists are urchins and street children he finds in street corners and teashops. The artist’s empathy for the underdog is evident in his works. The minor who is sometimes spotted carrying bricks at a construction site is his hero. Eruda 2006 is a fiberglass and steel sculpture of a young boy, his arms laden with books, with little knowledge of the contents of the paperbacks. He moves from one car to another to sell magazines and paperbacks during the short while when the traffic lights are yet to change, facing the hostile gazes of the occupants of the cars. Kallat’s barefoot sculptures are grounded in house-shaped cement, evoking the homelessness of the protagonist. Some of these works represent the collective human experience of sorrow as he observes the world. A disturbing yet thought-provoking piece is Ecto 2005. On view is a sculpture made out of black lead of a naked child drinking from the sprout of the kettle, arousing different emotions in the viewer. There is the innocence of the boy quenching his thirst and yet there is an undertone of a sexual gesture that evokes an uncomfortable feeling.

Death of Distance tells of sadder tales. In Death of Distance, five lenticular prints bring together differing experiences of living in India today. There are panels with different stories. Each of the panels highlight two conflicting news stories; the launch of ‘one rupee a minute’ telephone rates across India and a disturbing story of a girl who committed suicide because her mother couldn’t afford the one rupee she wanted for a school lunch. To make his point, he has created a firm rupee coin that is balanced on the gallery floor, while the two narratives bring forward two very different situations to the viewer.

Kallat’s paintings reflect the modern India as he sees it. Kallat captures the everyday ordinary existence of the metropolis. They appear scarred, marked with a texture that speaks of the layers found in Mumbai that reflect joy and anguish. As modern as they may appear, they root for the common man. Baggage Claim 2010 is an extraordinary painting of ordinary people, quite in league with paintings done by Bhupen Khakhar and Sudhir Patwardhan. These artists used the men in the street as their muse; in this painting there is a group of men informally sitting down celebrating a community spirit. They hold a squashed up crashed car and a collapsed home, symbolised by an insect-infested box. He again repeated a group of people sitting in Syzygy (2013), a sculpture made from dental plaster, but with a difference. They seem to be in a space between waking and sleeping, one leaning on the shoulder of another, enjoying a high comfort level and familiarity.

Humiliation Tax is a change from his earlier works in the colours and captions. Bright chromatic, pinks cyan and yellows dominate along with flatness in the surface. But what remain constant are the vivid reminders of street life although the artist’s style has changed. In the canvases, the children are transformed into psychedelic gods and goddesses amid swirling inscriptions of the name Ram, inspired by the Ramnami sect of Chhattisgarh that has been a major influence on the artist. Kallat’s urchins are an avatar of the child Krishna — the ultimate tribute.