For Pakistani-American artist Anila Quayyum Agha, 51, her art is her voice. Agha’s installations were part of the India Art Fair 2017 (Aicon Gallery, New York). Agha creates mixed media works on wide-ranging issues — from global politics and cultural multiplicity to mass media and gender roles.

Agha was born and raised in Lahore, Pakistan, and completed her undergraduate studies at the National College of Arts, Lahore. She moved to the US in December 1999. She started graduate school at the University of North Texas in 2001 and graduated with an MFA in fibre arts in May 2004. She moved to Houston in 2005 for an artist residency at the Contemporary Craft Center, Houston. From there, she moved to Indianapolis, in 2008 to take up an assistant professorship at Herron School of Art & Design/Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). Currently, she is an associate professor of drawing at the Herron School of Art & Design at IUPUI.

Talking about her installation All The Flowers Are For Me, she says, “It’s a rebellion, making a place for myself, being heard, but also, in the plural, letting other people be heard, making other people — the audience — realise that women and minority voices need to be heard because there is a lot of good stuff that comes out of them.”

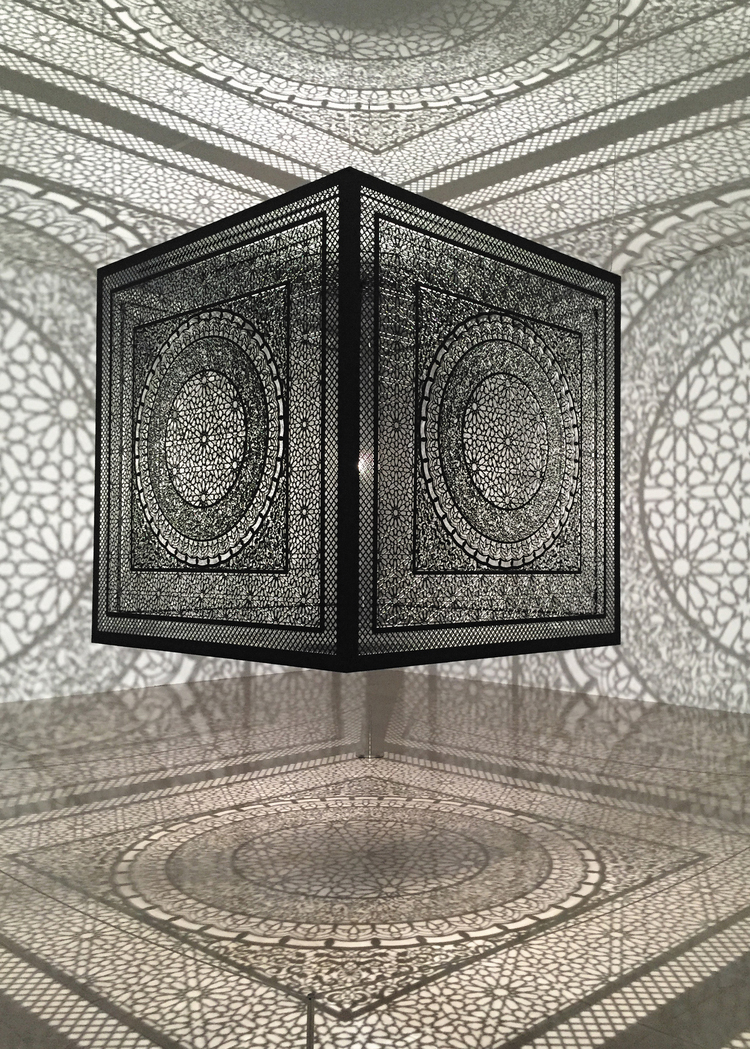

Agha’s single-room immersive installation, Intersections, is inspired by traditional Islamic architectural motifs. The laser-cut steel lantern conjures the design of the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain, a historic site of cross-cultural intersection where a thousand years ago Islamic and Western cultures thrived in coexistence.

In October 2014, Agha won both the Public and the Jury Award ($200,000 and and $100,000, respectively) at ArtPrize for Intersections. “My intent with this installation was to give substance to mutualism, exploring the binaries of public and private, light and shadow, and static and dynamic,” the artist had said in her statement then.

Excerpts from an interview:

NAWAID ANJUM: Let’s begin with your installation, All The Flowers Are For Me, which was part of the India Art Fair 2017 and generated a lot of interest among onlookers. It draws upon Islamic motifs and seems like a chiaroscuro of light and shadow. What does it symbolise? Could you share some of the ideas in your mind when you were working on it?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: My art practice is about social conditions and dealing with issues that affect women, minorities and not being heard. Intersections and then the subsequent light installations didn’t happen right at the beginning of my art practice. This work came after many years of working very hard to create artwork that was nuanced, subtle and evocative. My interest has always been to create a space where the viewer can look at the work and bring their own experiences into the fold. I don’t know if this actually happens when I make the work, but I try to find some way to connect with people and their experiences, through issues that affect them on a deeper level. For example, women in South Asia are often secondary to the male. And I’m not saying that they may be second-class citizens but they are secondary; their concerns, their well-being and health, their choices in life often come after the male has made the decisions. As a wife and mother my goals and desires will be less important than my husband’s or son. My interest has always been to make work that talks about that place where you’re not being heard or where you’re often the secondary. Intersections and its various derivations is a culmination of many years of working in that space and talking about my experiences as a young woman in Pakistan. Growing up as secondary, my choices were secondary and my place was secondary. It’s a rebellion, making a place for myself, being heard, but also, in the plural, letting other people be heard, making other people — the audience — realise that women and minority voices need to be heard because there is a lot of good stuff that comes out of them.

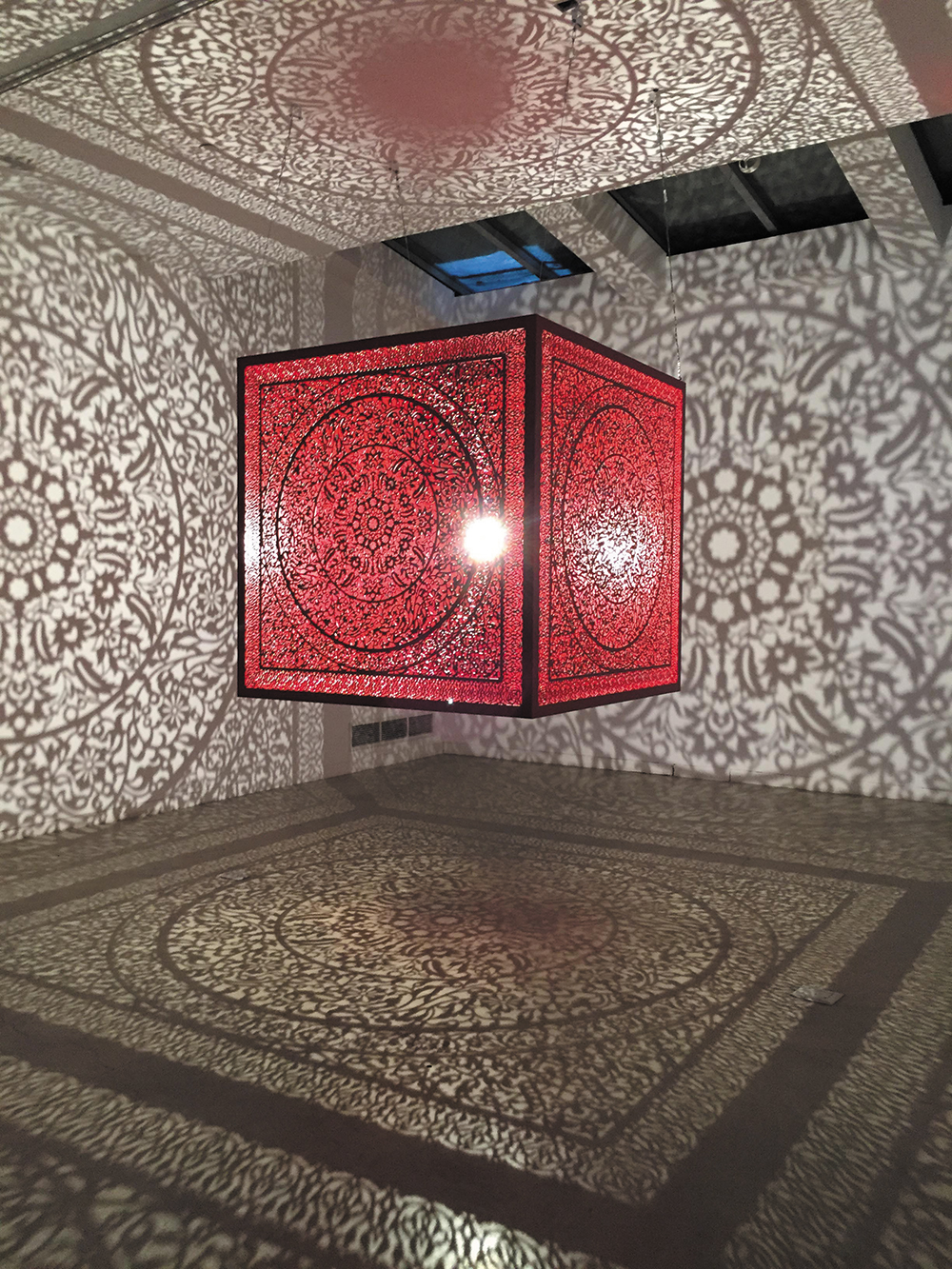

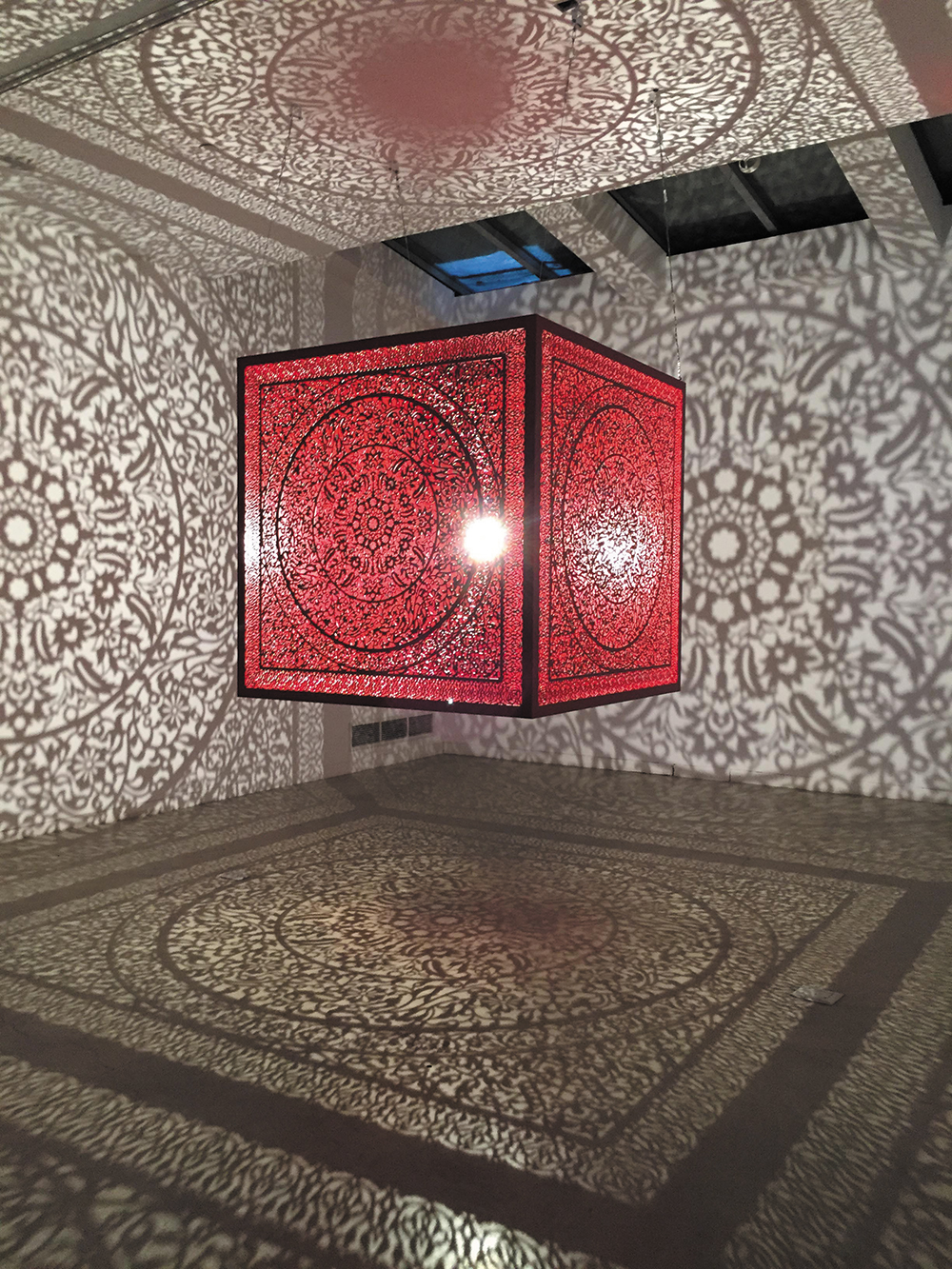

All the Flowers Are For Me, Red Lacquered steel and halogen bulb

60” x 60”x 60”

NAWAID ANJUM: At what levels do your works engage with a particular faith?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: I’m very interested in religion. It poses many challenges to the world population. It’s also a vehicle through which one can become intolerant and exclusionary. The general public has a tendency to castigate otherness, and cast aspirations on intent such as who is a true Muslim, Hindu, Jew or Christian or even a true Indian or Pakistani…See what is happening in the United States now.

I find religion to be a central part of culture. I have often thought that I as an artist can’t completely separate religion and culture as it’s an integral part of being alive, being part of a community. Since I was raised in the Islamic faith, even though I don’t practise it, I have a clearer understanding of what it means to be a woman from the Islamic world.

Having lived in the United States for the last 16 years, and having travelled to various parts of the world often, I find that there are ways to become intolerant. Even here, in the United States, Christianity can erode the humanity of people. And Islam and Hinduism can do the same. It’s very interesting to observe how to exclude people, on the basis of skin colour or religious practice. In my opinion it’s all really tied to economics. If economies are better, people will be okay and will live in harmony in spite of differences. However, hard economic times affecting the well-being of families like shelter, food, healthcare can turn people against neighbours and others because they look different. As an artist, I find that paradigm interesting and it informs my work. That is often how women have been reduced to being secondary. Some religions apparently suggest that women are less...having come from Adam’s rib, etc. Ritual and not doctrine in Islam frowns upon women going out of their homes because men are supposed to provide for them. So, basically taking away a woman’s right to exist as a full person, and suggesting we are incapable of taking care of ourselves or to chart our own lives by confining us under the umbrella of a man. I find that very connected to religious dogma and interpretation. I also think religions are man-made and created for control. If they are truly sent by God, (if there is a God), then the interesting thing is that some men have interpreted it to control the world to their liking. Often, my work is connected to the phenomenon of culture, religion, doctrine and ritual corresponding to belief patterns. I’m interested in creating a liminal space that’s higher and more humane for people to exist within, to create dialogue, to find a moment of compatibility which may not be peace, but something similar… I also think beauty can be quite banal and boring after a while… So, as an artist, I want to create a space that’s constantly evolving, changing, and not always beautiful. In my light installations, while walking through the space, people’s shadows change the environment, making it experiential. Beauty moves, it’s fluid. And I find dialogue about beauty and ugliness fascinating.

NAWAID ANJUM: Do your experiences as an immigrant and the bi-cultural assimilations also inform your work?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: The sense of displacement never leaves you when you leave your home and move elsewhere… when I left Pakistan, it took me 2-3 years to really get acclimatised to the United States. Even now, there are people who will often correct my English the American way… (Laughs).

I think loneliness as an immigrant is intense. I often gravitated towards areas where I’d see people who looked like me. Like a lot of Pakistani expatriates will live in neighbourhoods with other Pakistanis or Desis. I often went to desi restaurants to just feel a part of the community.

I also think in America, there are a lot of loud conversations or sometimes noise between the white and the black communities. People, who are migrants from other nations, like the Far East, South Asians and from both the African and South American continents, their voices are very tiny here in comparison. Racial layers need to be unpacked to further expand the conversation between all races.

People who emigrated from South Asia to the United States in the 1960s, 1970s and the 1980s were more literate. There is an expectation that South Asian people are extremely well-educated and smart. There are a number of South Asian tech billionaires in California. Some years ago, the Nobel Prize was given to a Bangladeshi. The medical industry is dotted with people from the countries in the MANASA region. To sum up, there is an expectation that South Asian people are generally more educated which is helpful to our community. But recent topical events such as the Trump presidency, have unleashed a backlash towards people who look different. And diverse people across the country are being told to go back home. I think globalization, tough economy and wars worldwide are the cause of this sentiment in the West. And people deal with such issues by targeting a particular race or religion and identifying it as the problem. Right now in the USA, immigrants are the problem. “They are taking our jobs so get rid of them.” But diversity, in my opinion, makes things better through new and fresh ideas which help to grow the economy. However, an unfortunate side-effect of the immigration movement in terms of Pakistan or South Asia is the brain drain through the loss of smart and educated people moving to the United States to make better lives for their families. Whilst sadly the political turmoil continues in South Asia.

The immigrant experience can never fully leave us. In my university where I teach, I’m the only South Asian at the Art school. Even though I speak English perfectly well, albeit with an accent, I have to explain things more clearly. I do believe life can be good if you make it good. Through hard work there is a possibility in the USA to live an above-average life for immigrants and their families. I see people excel here.

I don’t know how the future with Trump is going to be. But in the last 15-16 years, I have been able to make a good life for myself here. I have been able to make artwork that is interesting, political and social-oriented, without barriers. I wonder if I would have been allowed to do it in Pakistan. Although, now I think about it, there are lots of artists in Pakistan who are doing some amazing work. It’s a bean bag with thousands of beans. You can do whatever with it. (Smiles)

Alahambra Nights, acrylic and halogen bulb, 30” x 27” x 30” 30" x 27" x 30"

NAWAID ANJUM: It seems to be a dark moment in history, with conservative forces at the helm of affairs in major countries of the world, and the liberals increasingly being overshadowed. As an artist, how do you look at this phase? What hope does the future hold out?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: If you think about it, historically within the last 200 years, there have been waves of liberal thought across the world and then it switches to more conservative outlook. This era right now is moving towards more conservative behaviours and patterns. It seems like we are heading towards the more Victorian style which is pretty dark for the whole world. I do think it’s connected to the world economy. Population is growing intensely, with inadequate opportunities. A large percentage of the world capital is in limited hands while the multitude doesn’t have access to it. There is always going to be this ebb and flow.

Often work that is really cutting edge comes from this high contrast of ebb and flow. The Russian Revolution produced some of the best writers. The Impressionist painters made very interesting work at a time of deep conservatism. Likewise, works of contemporary Pakistani artists like Imran Qureshi are in response to the violence in Pakistan right now. I find that there is a way for artists to survive. I think it will be hard as politicians will try to control and silence us. But I am optimistic that creative people will find a way to continue to say what they want to say, through sarcasm or other means available to them. Currently in the USA, Saturday Night Live or SNL is producing the most wonderful response topically. To me criticism is acceptable but not being silenced. I’m a blue collar worker and work all the time in the studio or at the university. I have an interest in sparking dialogue without censorship. That’s one of the reasons that I won’t return to live in Pakistan because I think people are silenced there and that is tragic to me. In my opinion, Pakistan as a society would do better by giving free reign to their writers, intellectuals and artists, promoting dialogue and encouraging literacy. But, unfortunately, it’s a society that is about control and frowns upon people thinking for themselves. I think this control possibly happens in India too, but I don’t want to speak for India. And unfortunately going forward this trend may happen in the United States too as a lot of close-minded people came into power recently.

NAWAID ANJUM: As an immigrant, how do you look at belonging?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: When I came here 16 years ago, I found it really difficult to become assimilated in the first few years. It took me three years to fully feel like I belonged here. And then I don’t know if one can ever fully belong. The thing that really made an impression on me when I started graduate school was that my cultural difference was my strength. And then I also spoke with an accent. That, in some ways — not that I capitalised on it — helped me realise that difference is not a bad thing. In fact, having a different way of thinking, and looking, knowing skills and doing certain things better than the American students was quite an interesting way to assimilate. And then I had to learn a lot of stuff they knew. There was an exchange of knowledge and skills, making it challenging. It was interesting that I brought something to the table that wasn’t existent here already. I celebrate that difference now with my students and myself. Nobody should be worried about not fitting in. The cultural, racial and economic diversity allows for many streams of thought and action which should be celebrated. There are many people who would like to assimilate more which usually happens when you are very young. In one’s teenage years, we all want to belong as differences make us the targets. But as I have grown older, I’ve realised that my strength is my difference. I’m never ashamed of being who I am. Of course, I’ve always wanted to grow and be able to educate myself continuously, but I think I’m very interested in maintaining the difference, contributing towards a dialogue from my perspective. For example, when I go to somebody’s house for dinner — usually over here you bring something — I bring something Pakistani to the mix and all my friends know to expect spicy food from me. So, the difference adds to the interest.

NAWAID ANJUM: Could you talk about your influences? How important are the ideas of space, form and structure to you as an artist?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: I’m very interested in both the conceptual and formal qualities of art. Historical discussions of women create the expectation that women are delicate, fragile and beautiful. While the subject of men includes qualities dealing with masculinity and strength. In my art practice, I think about the contrasts and commonalities. I also think about the formal qualities of how perceptions can be created. For instance, the use of steel in the light sculptures denotes strength and hardiness, and quite possibly is the strongest material available to me. It’s possible that these sculptures would survive a nuclear war. Combining the delicacy of floral and geometric patterns combined with levitation informs my concept; strength and fragility. It’s a statement. Strength can also be fragile, feminine can be masculine, and what is levitating can also be very heavy. Because of the deep red or black colour of the sculptures, there is a heavy visual weight associated with them, and yet they float. And the single light source makes them even lighter. These contrasts are fascinating for me. I’m also very particular about the use of craft. I’m quite compulsive about keeping things balanced and tight. Asymmetrical or symmetrical, the artwork has to feel balanced. I don’t use found objects in my artwork because I find that I have to craft things perfectly and they have to balance. That is the reason why my sculpture work looks formally elegant. My drawings also have the same quality of being perfectly conceived and executed. The embroidery may seem like a machine was used, but actually I do it by hand. And then all the colours like red or black have to be matt instead of shiny. All my artwork shown at the India Art Fair was about the independence or lack thereof and what it means to be a woman in South Asia. A woman’s life is tied to child-bearing and motherhood. Secondary! Although that’s such an oxymoron concept, as a mother’s work is probably the most important. So, All The Flowers Are For Me was to celebrate women and what they mean to the community, and the larger culture. For example, I wonder what would happen to India, if women went on strike. In my work, an art piece is floral yet the red colour can be considered violent or passionate; it can be considered a number of things.

Intersections, lacquered wood and halogen bulb, 78” x 78” x 78”

NAWAID ANJUM: How have your works been received by people across the world?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: In the United States, it has been received really well. It may be due to topical sentiments of solidarity towards the Islamic countries that are on the ban list. The academic world in the United State is really very forward-thinking. Since here I occupy the space of an academic, it really helps to be surrounded by intellectuals or people who have an understanding of cultural differences and are accepting of diversity. Being an artist and an academician here in the USA, there are a lot of really nice gestures from colleagues, professionals, and students. It’s different when we go out into the bigger world outside of the university campus. Over the last 2-3 years, I have shown my work in many different places. The installations have travelled within the United States as well as to India, United Arab Emirates, Korea, Turkey and Spain and will travel to Hong Kong and Singapore in 2017.

People generally forget what an amazing history the Islamic world has provided to the world, such as architecture, geometric and floral patterning and craftwork. No doubt, ISIS is not helping the Muslim community because they are obviously barbarians and need to be contained. There is also a misconception in the West that the Islamic world is intolerant. However, there are millions of people who practise it peacefully. So, this is like a reminder to people here in the United States that there are finer concepts coming from the Islamic tradition as well which create a strong impact.

After Intersections was shown in the United States and won two big awards, I often wonder why it resonated so much with the audiences here and elsewhere. The answer to that question may be that it provides a moment of hope. It creates a space where we can possibly rise above ourselves. It allows people to see each other in a different way. Everybody looks beautiful inside that space. I often think about the effect on people’s psyche to walk through a liminal space. Fascinating questions and train of thought!

NAWAID ANJUM: How do your own students respond to your work? What’s your approach to teaching art?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: Teaching art is very subjective. And there is no real formula that one can use to make people think a certain way. One can teach them the concepts and mechanics — like how to draw, measure, create value or understand colour theory, as well as various processes like drawing, sculpting, welding or printing etc. Thinking and conceptualising an artwork is a very individual methodology. My goal always is to facilitate the artist in the student. And that’s sometimes a difficult thing to do because young people may come in with a mindset. And often young people can be pretty self-absorbed and may think their way is the right way. With age, advancement and experience, going through their four-year degree programme, they start loosening up.

Simultaneously there’s another phenomenon happening. Freshmen students are childlike and are learning how to think and use correct words to describe something, or talk about perspective and form. It’s like one needs to nurture them, but also make them strong in a way that they can think for themselves. So, teaching art is an art form in itself. It can be very complicated and really onerous, both on the teacher and the student. My job as an art teacher is to facilitate my students with their art concepts and processes all the while allowing them to come to their own realisations both in the present and future. After graduation they then have to find their own way which can be hard in a culture that may not value an artist. A parent may not want to see their kids go through the hardships that are associated with being an artist. Often, the parent can say, “No, I don’t think I want to pay for that.” So, the students have to have determination, abiding interest and deep commitment to their work. I think my students see that strong work ethic and discipline in my work. A few alumni from Herron who work for me know I work all the time. I’m also very interested in moving on to the next thing and exploring another facet of something I may have worked on previously. I’m currently starting a project that’s possibly 12-ft tall. That will be really interesting in terms of size and scale. I feel that my students realise how hard it is to make artwork and build a career. If one wants to live an artistic life, then working all the time, both mentally and physically is a must.

NAWAID ANJUM: How important is the medium for you? How do you choose it for any particular work?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: People in India and other places are more familiar with my light installations. Although some of my drawings were also exhibited at the India Art Fair this year. In the past, I have made installation works with threads and thorns. I always think of the concept first, then I make the work based on what I’m trying to say. Often, the process as well as the material is used to amplify my idea. For me, it’s really important that all three things come together at the same time and they convey an idea in a very beautiful and effective way. It has to be concept, material and process — all bound together flawlessly.

NAWAID ANJUM: Where do you draw your inspiration from? What are some of the other stuff that you enjoy doing?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: I teach full time and just got back from sabbatical. I teach five classes a year and that occupies a large chunk of my time. I order art supplies/ materials online to minimise my time away from the studio. For recreation, during the spring and summer, I enjoy cycling. I like music and movies a lot, and tend to eat ethnic foods quite a bit. During the semester, I read more art-related periodicals. But when I have free time, during summer or winter breaks, I read literature. I’m really excited about Arundhati Roy’s next novel and waiting breathlessly for it. Studio and university work occupies my mind a lot. And since we have to do everything here ourselves, like cooking and cleaning, etc, all this keeps me busy.

NAWAID ANJUM: What should be the role of an artist in a changing world?

ANILA QUAYYUM AGHA: In my opinion, all of us have to be activists — all of us! It’s not just a role for artists or the intellectuals. I do think for me as an artist, to be honest to myself, truthful, yet critical, is what makes my work better. Lying to myself will make my work more commercial, and I won’t be happy. I feel that honesty, interest in getting to the bottom of things, trying to find the crux of the matter, understanding culture and how it impacts the individual and communities will always be something I go back to, to understand and make artwork from. I think experience and travel really help me a great deal. I hope that I’d be able to continue to travel. In fact, I’m supposed to visit Pakistan this year. I wish I could come to India, but I think it’s harder for Pakistani-Americans to come to India now. It has been so for a long time.

I worry about places like Pakistan and India where people moralise rather than looking inwards. There is a constant play of, “I’m holier than you…I’m better than you.”

I spend time reading and trying to understand human nature. I think, as an artist, I will always be introspective and feel that’s something that seems absent in countries like Pakistan… with people there often trying to justify their own purity at the expense of others. I hope that I continue to do work that is sound, subtle and strong. I don’t have any interest in moralising, but trying to understand. I think comprehension is an integral part of what I do.