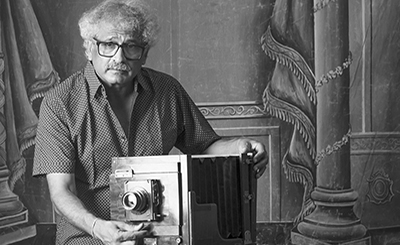

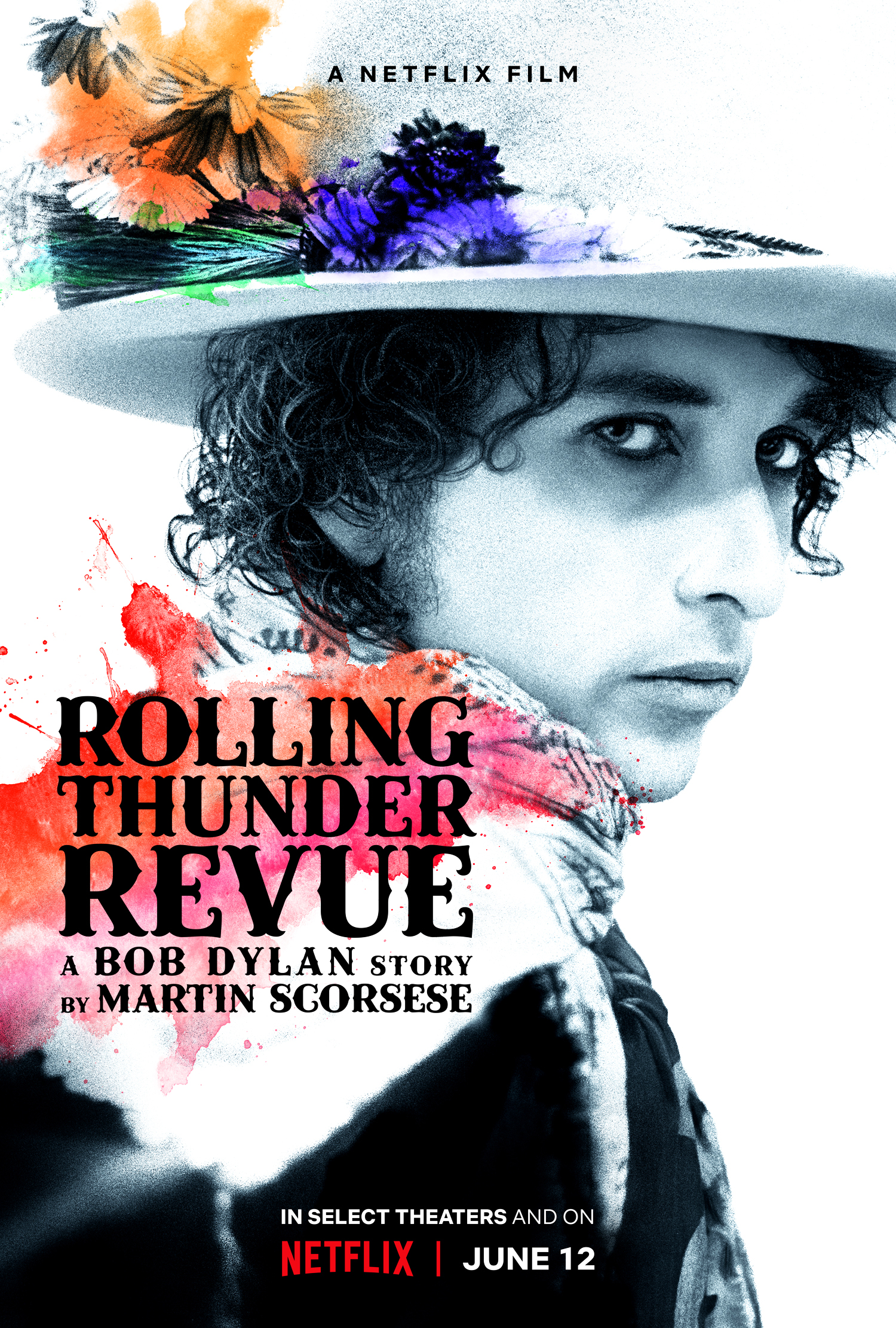

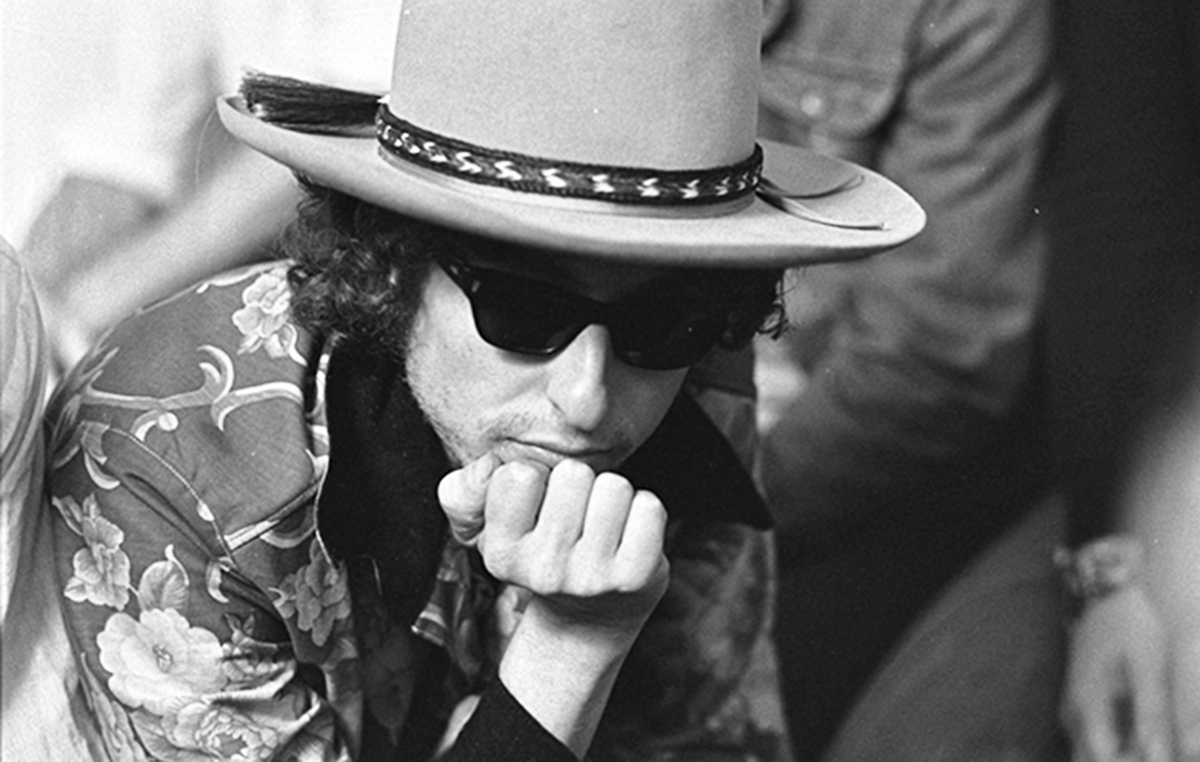

Bob Dylan (above). Photo courtesy Clash Music Magazine. A poster and a still (below) from The Rolling Thunder Revue, directed by Martin Scorsese

Where there is Dylan there is legend, greatness and fecundity. There is also present, lurking behind the shades, a glint of profound mischief. The Rolling Thunder tour film is a shining example.

My earliest memory of Dylan is the preparation and planning that went into the simple act of listening to Dylan for the first time.

In the 1980s only some of Dylan’s work was available in India on CBS, but not all. The pirate was the repository of musical knowledge and information. To get into Dylan, to start one’s journey, required a three-pronged strategy:

1. Locate a pirate who had the goods.

2. Procure a good quality long-last blank audio cassette, preferably of Japanese make.

3. Decide on which Dylan albums to begin the journey with, under guidance of said pirate.

I found the pirate near the Dehradun clock-tower. He wore his hair bunched into a ponytail, had an impressive wardrobe of flowery shirts and owned a cassette and video rental shop. Venus had a camera print of Jurassic Park on VHS, the day it released in America.

The name of the owner doesn’t matter; Venus was the brand-name; the pirate was known as ‘the Venus guy’. He, unusually, was a Bob Dylan fan. In his Lilliputian store, Dylan blared from chest-high speakers at all times.

Mr Venus had several book-like CD albums, stuffed with country, reggae, pop, rock and the entire NOW series — which he recorded on cassette for a fee — and most of Dylan’s back catalogue. While I’d managed to locate the fountainhead, I lacked the hardware: the Japanese blank cassette. Mr Venus had stacks of Meltrack and T-Series blank tapes, but they had a reputation of being flimsy. When the rains came, the tapes developed a white coat of fungus. Dylan, it seemed to me, was going to be a life- long affair, so I better have his music carved in stone.

Dehradun was where my grandmother lived; it was a town I visited in the summer vacations. I shelved my Dylan plans for a year because of the elusive affordable good-quality cassette tape. Mr Venus offered to get me some Sony blanks from the black market but at an exorbitant price, way out of my schoolboy budget. I had other plans.

My aunt, my father’s sister, lived in Gorakhpur, near the Nepal border. In those days, it was standard practice to go to the Border in buses to shop for cut-price electronics, a casual Sunday outing in another country. I asked my aunt to get me two TDK blanks, which she did. A year went by. I returned to Dehradun, armed with the two TDKs, my secret contraband, and duly handed them over to Mr Venus. The first two albums he recommended and recorded for me were The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (fun, 1963) and Highway 61 Revisited (dead serious, 1965). My Dylan journey was finally underway.

It would be ten years later, in the late 1990s, that I bought my first Dylan L.P., Blood on the Tracks, as a student in Oxford. It was the beginning of a new romance: Dylan on vinyl, as it should be. Meanwhile, the TDK tapes, true to reputation, are still going strong, having survived many Dehradun monsoons. So is Bob Dylan. Venus though was decimated by the churn in the music industry: cassette to CD to Torrent to streaming. Mr Venus has shifted to selling “car audio”.

*

Bob Dylan turned 78 this year, just a few years older than my parents, very much a creature of their generation. He is still touring; on YouTube, there’s a video of him admonishing a Vienna audience aiming their cameras at the stage: “We can either pose or play, ok?” grumbles Dylan, as he stumbles over a monitor and avoids falling and breaking his hip by a whisker.

It’s the problem with being famous; the faceless crowd, after a point, begins to resemble an unruly classroom. The hero is reduced to being a tetchy schoolmaster, while the worshipping, paying, praying fans try to be on best behaviour and stay out of the hero’s way.

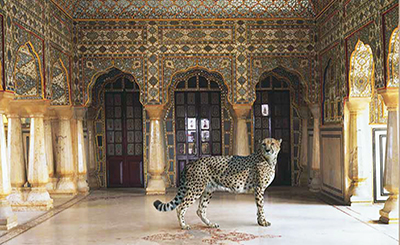

The new Dylan documentary on Netflix, The Rolling Thunder Revue, directed by Martin Scorsese, features Dylan and a cast of characters, playing small venues across America, mostly New England, in 1975, the year I was born. This was at a time when Dylan was tired of playing packed stadium gigs and yearned for a more intimate experience. It marked a return to his coffee-house roots.

To get a sense of the time, one has only to read the liner notes on Blood on the Tracks, written by Irish-American writer Pete Hamill. Dylan, by 1974, was already an industry: “So forget the clenched young scholars who analyse his rhymes to dust. Remember that he gave us voice. When our innocence died forever, Bob Dylan made that moment into art. The wonder is that he survived...Of all our poets, Dylan is the one who has most clearly taken the roiled sea and put it in a glass...His poetry, his troubador’s travelling art, seems to me to be more meaningful than ever. I thought listening to these songs, of the words of Yeats, walker of the roads of Ireland: ‘We make out of the quarrel with others rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.’”

The Rolling Thunder Revue presents to us rare concert footage of that legendary tour featuring Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Ramblin Jack Eliott, Roger McGuinn and the violinist Scarlet Rivera. Everyone is along for the ride and making up things as they go along. A deferential balding Allan Ginsberg, curly hair hanging like loosened pig tails on either side of his face, happily agrees to restrict his part performing Howl to two minutes in order to accommodate the ever-expanding band of musicians. Ginsberg and Dylan hang out at Kerouac’s grave; Dylan fools around with a harmonium.

Dylan recalls: “He danced a lot, Ginsberg.” The others on tour remember a sober Ginsberg and refer to him as a saint or a father figure. Dylan pronounces with ironic certainty: “He was definitely not a father figure.” Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg’s boyfriend, was on the Rolling Thunder Revue tour (October 30, 1975-May 25, 1976) as well, and happily acknowledges on camera that his job is to run errands and be the ‘baggage handler’.

Parts of the documentary are made up, which makes this a cat and mouse game for the viewer. Sharon Stone pretends to be a wide-eyed teenager who turned up to watch a gig with her mother, back in the day, and who was tricked by a caddish Dylan about a song ostensibly inspired by her. She even cries a fake tear. The truth is she was never there.

Van Tropp, who speaks at length in the documentary, is an invention, an actor feigning to be the original film-maker whose footage is being utilised by Scorsese. Nevertheless, he puts his finger on the pulse: “The concerts were like one battery charging another. One could not only feel the vibes but see them. Is Dylan a genius? I don’t know; it’s a strange word. The most brilliant thing he did with this tour was to put a group of highly motivated and ambitious people on a train with no supervision, and allowed them to become the most extreme version of themselves.”

That is what we get as the merry band travels from town to town — St Peterberg, Florida; Hattiesberg, Mississippi; Corpus Christi, Texas; Mobile, Alabama, and around sixty others. The tour van, at all times, has Dylan at the wheel, driving the mad circus into unsuspecting towns. Many of the concerts are sit-down ones, providing a stark contrast to the energy swirling around on the stage. The attendees include men, women, white folk, black folk and native Americans.

As the documentary begins, Dylan jokes: “I don’t remember the Rolling Thunder Revue. I wasn’t even born then. It was something that happened forty years ago. It was nothing.”

Later on, Ginsberg argues that everyone involved in the tour was “trying to recover America” (1975 marked America’s bicentenary), while Dylan acknowledges it might have been a “success”, not so much measured in profit but as an “adventure”. Ginsberg even manages to extract an aesthetic-moral purpose from it, that we should try and be the best creative people that we can be. To realise that ambition, advises Ginsberg, be “mindful of one’s friends and mindful of one’s art.”

*

Dylan’s voice has changed over the years from velvety to nasal to desert-dry; he has turned several avatars from acoustic to electric; but Dylan hasn’t stopped performing and putting out new material. He’s written love songs, drunk songs, zeitgeist songs and pamphlets of prophecy. A scribbled note from his diary forms the epigraph to Bob Dylan: Writings and Drawings (Grafton, 1972): “If I can’t please everybody/ I might as well not please nobody at all/ (there’s but so many people/ an I just can’t please them all)’ (sic).

For me, it’s always the storytelling that stays with me and draws me back to him. Dylan performing live in Rolling Thunder is Dylan saying: “Come and gather round me and I’ll tell you a story.”

At the age of twenty-two he wrote The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll:

“William Zanzinger killed poor Hattie Carroll,

With a cane that he twirled around his diamond ring finger...

At a Baltimore hotel society gath’rin’.

And the cops were called in and his weapon took from him,

As they rode him in custody down to the station.”

In 1964, he recorded Seven Curses but left it out of the album The Times They Are A Changin’:

Old Reilly stole a stallion

But they caught him and brought him back

And they laid him down the jailhouse ground

With an iron chain around his neck.

Dylan wrote several songs about boxers; a year before he recorded Seven Curses, he wrote Who Killed Davy Moore:

Who killed Davey Moore,

Why an' what's the reason for?

"Not I, " says the referee,

"Don't point your finger at me.

I could've stopped it in the eighth

An' maybe kept him from his fate,

But the crowd would've booed, I'm sure,

At not gettin' their money's worth.

It's too bad he had to go,

But there was a pressure on me too, you know.

It wasn't me that made him fall.

No, you can't blame me at all."

In Rolling Thunder, he performs Hurricane, the opening track on the Desire album (released in 1976, soon after the tour concluded), about a black boxer wrongfully confined to prison:

“Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night,

Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall,

She sees the bartender in a pool of blood,

Cries out, “My God, they killed them all!”

Three bodies lying there does Patty see,

And another man named Bello, moving around mysteriously,

“I didn’t do it,” he says, and he throws up his hands,

“I was only robbing the register, I hope you understand.

I saw them leaving,” he says, and he stops,

“One of us had better call up the cops.”

The storytelling powers have not faded on his 1997 album, Time Out of Mind, his 30th, especially on a track called Highlands — a repartee song — in which Dylan’s character is having a conversation with a Boston waitress:

“Then she says, “I know you’re an artist, draw a picture of me!”

I say, “I would if I could, but

I don’t do sketches from memory”

“Well,” she says, “I’m right here in front of you, or haven’t you looked?”

I say, “All right, I know, but I don’t have my drawing book!”

She gives me a napkin, she says, “You can do it on that”

I say, “Yes I could, but

I don’t know where my pencil is at!”

She pulls one out from behind her ear

She says, “All right now, go ahead, draw me, I’m standing right here”

I make a few lines and I show it for her to see

Well she takes the napkin and throws it back

And says, “That don’t look a thing like me!”

I said, “Oh, kind Miss, it most certainly does”

She says, “You must be jokin’.” I say, “I wish I was!”

Then she says, “You don’t read women authors, do you?”

Least that’s what I think I hear her say

“Well,” I say, “how would you know and what would it matter anyway?”

“Well,” she says, “you just don’t seem like you do!”

I said, “You’re way wrong”

She says, “Which ones have you read then?” I say, “I read Erica Jong!”

Where there is Dylan there is legend, greatness and fecundity. There is also present, lurking behind the shades, a glint of profound mischief. The Rolling Thunder tour film is a shining example.

This piece is brought to you with the support of Jayshree Misra Tripathi. If you wish to sponsor an article, interview or cover interviews/essays, write to us at [email protected]/[email protected]. You can also WhatsApp us at 9871613696

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated