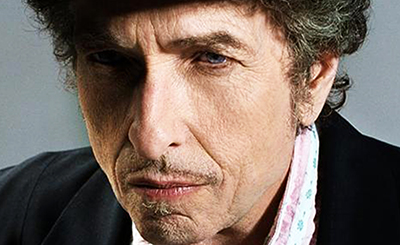

Writer, performer and director Mahmood Farooqui. Photo courtesy of Uma Prakash

The writer, performer and director on his attempts at reviving the art of storytelling that has been coming down for centuries

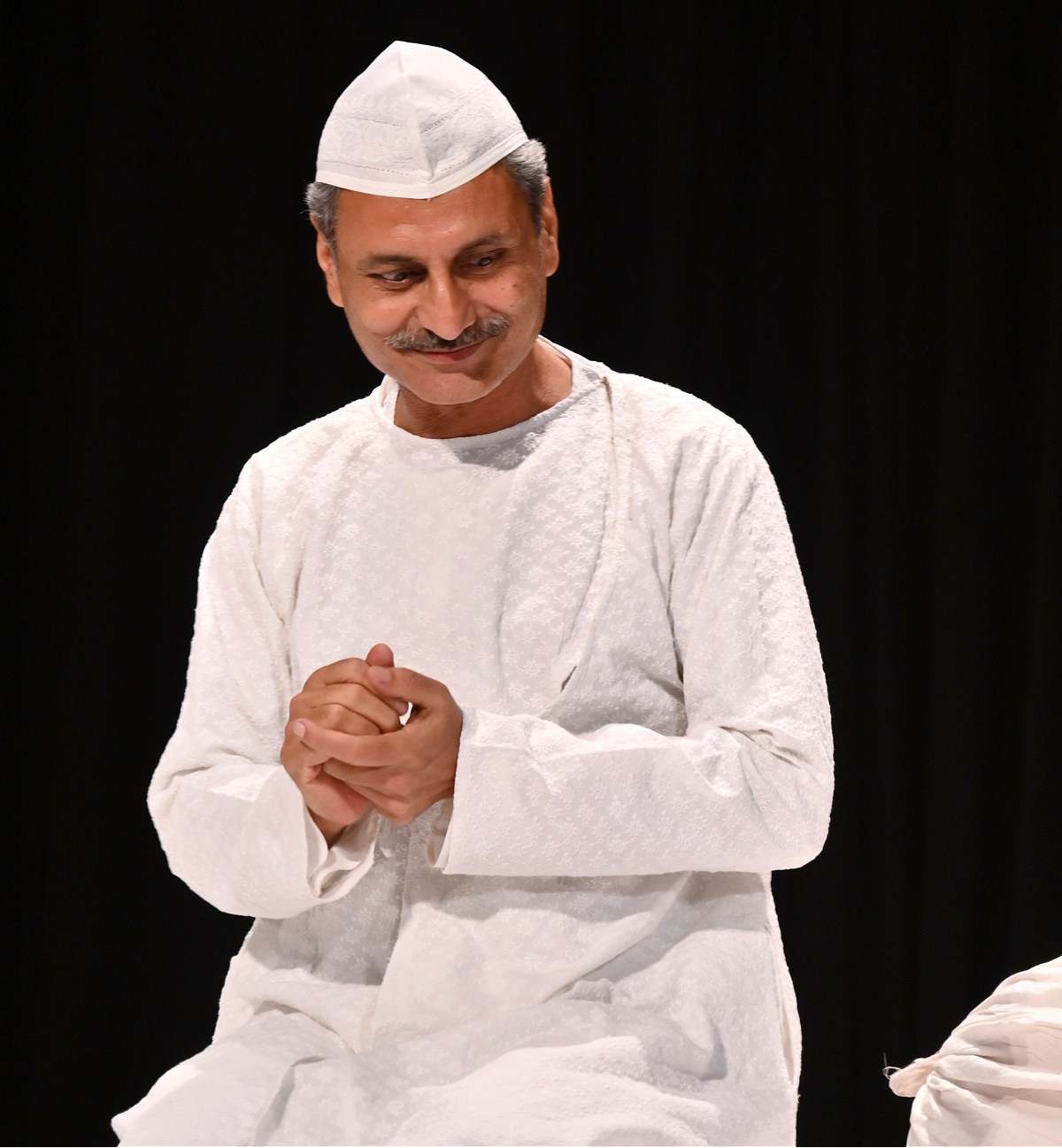

The stage is dark and light dramatically falls on a white gadda/mattress covered by a spotless white bedspread. There are two bolsters with white covers on either side. Two big white candles are placed on either side and the scene is set. Enter Mahmood Farooqui and Darain Shahidi, the two dastangos (storytellers) in crisp white angarkhas and white topis. They sit on the gadda and unfold folk tales of distant lands, engaging and enthralling the audience.

Dastangoi is an art of storytelling that has been coming down for centuries. It has been revived by Farooqui, an award-winning writer and performer. He was awarded the Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar by the Sangeet Natak Akademi of the Union Government for his effort in reviving dastangoi. His book on the 1857 uprising, Besieged: Voices from Delhi, 1857 (2010), was awarded the Ramnath Goenka Award for best non-fiction book of the year by The Indian Express Group. He has been a Visiting Fellow at the Universities of Michigan, US and Berkeley, California and was a Rhodes scholar from India at the University of Oxford and at the University of Cambridge. His latest book is A Requiem for Pakistan: The World of Intizar Husain (2016). Excerpts from an interview:

Tell us about your academic trajectory from a school in Gorakhpur to securing a Rhodes scholarship at the University of Oxford.

From Gorakhpur, I won a Government of India scholarship to study at the Doon School, Dehradun, and thence to St Stephen’s Delhi to study history. I studied history for the first time and really enjoyed it and was awarded the Rhodes scholarship to study at Oxford. I got a Top First at Oxford, which means I was among the top three in the University, and was awarded the Gibbs Prize for History and the Carl Albert Award for being the Best Graduate of the year at St Stephen’s. Thereafter I went to Cambridge University for an M Phil and after that I was faced with the choice of doing a PhD and committing myself to an academic career but theatre was calling me so I returned to India.

When did you first realize you were interested in theatre and which actors influenced you?

I discovered a love for the stage as a young child thanks to my father who would write speeches for me to memorise and deliver on stage. Later, at the Doon School I got my first full exposure to theatre when I saw Naseeruddin Shah and Benjamin Gilani perform Waiting for Godot. It was also there that I first acted in plays. Mohan Maharishi, sometime Director of NSD came to the school and directed Oedipus Rex where I was also the Stage Manager and this gave me a huge fillip. In my final year, I produced and directed Tughlaq that was much praised. Later in college, with the Shakespeare Society, I did several plays and directed more than one. This continued in the later years too. I also acted in the stage on Bombay with Atul Kumar and the Company Theatre.

After being an academic for so many years how did you suddenly shift to performing art?

I had been a student of history and had an interest in Urdu literature and had been involved in theatre so when I read S. R. Faruqi’s magnificent book on Dastangoi, I was immediately hooked and began to plan its revival and popularisation. I was already making documentaries, had made one on Habib Tanvir, had been in the media as a Reporter with NDTV and knew that I wanted to make a career in the performing Arts so the book came as a Godsent and literally changed my life.

Dastango is an old art form that became popular in the 19th century but with the demise of Mir Baqar Ali in 1928, the last exponent of the art form, it also waned. How did you and SR Faruqi revive it?

We had no models, no previous performers, nothing that we had seen. We worked closely with S.R. Faruqi and I used my intuition as a theatre person to bring in two performers and roped in my old school friend and theatres associate Himanshu Tyagi for the first show. By then I had read the stories included in the Dastan-e-Amir Hamza and I knew they were awesome in terms of plot, suspense, dialogue, creativity and imagination, far surpassing anything I had read in literature and drama and I knew that if performed well they would work. Our performance was a cross between the traditional ones and modern stage acting and from the very first show in May 2005, it worked and worked magnificently and we never looked back. Later, I took workshops and trained several people in the Art form.

The wonderful tale of Chouboli was first translated from Rajasthani into English by Christie Myril from the Michigan University. What fascinated you most about this tale to translate it and give it the dastan avatar?

Chauboli has been our greatest hit and has been performed over a hundred times by over ten different pair of performers and is always a hit. I chose it for its story within story format and it was the third modern story I devised for the stage after Dastan-e Partition and Dastan-e Sedition. Folk stories are generically close to Dastans, have the same flavour and are timeless. They also cut across the class divide as they appeal to the educated and the illiterate both. I also loved what Detha ji did with the stories adapting and commenting on them from his progressive ideological standpoint. It was a great experience to perform it at Michigan with Christie Merrill the original translator as a member of the audience and to have a Question-Answer session with her too.

You have trained several youngsters in the art of dastangoi. You have picked topics like the Partition and Gandhi as your stories. How do you see the future of Dastangoi?

Over the last 17 years, we have trained nearly 50 people in the art form and nearly half a dozen of those are making their living off the form. That is remarkable. Overall, the Collective has performed nearly 800 shows and we have produced over 15 modern dastans written and compiled by members of the group under our Direction. Dastan-e Partition, Dastan-e Sedition, Dastan-e Mantoiyat, Dastan-e Mahabharat, Dastan-e Jai Ram Ji Ki, Dastan-e Chauboli have each had several, in some cases, more than a hundred outings, some of which are showcased in the festival. There are three books on Dastangoi, a participation in the major festivals in India and abroad, including Rekhta, JLF, Times Literature Festival, and now Dastangoi is being performed in Marathi, Bengali and Gujarati and even in Pakistan, which is a tribute to the vision of our patron the late S. R. Faruqi and the love and appreciation we have received from the audiences in India and abroad. I think the future is really bright.

When you performed Dastan-e- Karan Art in Gurgaon Utsav you completely mesmerized the audience as you used Urdu, Hindi, Sanskrit, and Farsi languages to communicate your story. What sort of research went into it?

A lifetime of research I should say. A lot of my historical readings, my training in Urdu, especially my close reading of Intizar Husain on whom I drew a lot. Also my learnings with the late Mujeeb Rizvi, the great scholar of medieval poetry and culture and many things I learnt from my father, the late Mahboob Ur Rahman Farooqui and of course the writings of my mentor S. R. Faruqi, a scholar non pareil.

How will Geetanjali Shree’s Booker prize win for her novel, Tombs of Sand, impact the status of other stories written in Asian languages?

I think it is a tremendous boost for all of us who work in non-English forms and modes. It has given us a great fillip and hopefully will encourage many to take their own linguistic and cultural heritage more seriously.

What is your latest book, A Requiem for Pakistan: The World of Intizar Husain about?

It is about the writings of Intizar Husain one of the greatest of modern Urdu writers and a very unique voice who wrote much about Hindu mythology, about Buddhism and the Jataka stories, who was inspired by Kafka and by the Puranas, who wrote existential stories as well as reworked folk stories and who also cared deeply about the environment and about the depredations wrought by man on man and on nature. He was born in India and moved to Pakistan later on and was accused by nostalgia by one and of being a turncoat by the other so had a very interesting liminal position. I love his prose and the stuff he wrote about.

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated