I reconstruct my first meeting with Shravan, altered with the weight of forensic evidence. I still attempt to solve this cold case from my youth. Yes, it was murder, but not the fun Agatha Christie kind. It was a boring slaying; an annihilation of my dreams. Not a malicious homicide either. Involuntary manslaughter, by negligence.

There are no red flags that stand out in my memory. Convent school English, sociable, nice smile. Shravan radiated warmth. His boyish enthusiasm at the prospect of his marriage was delightful. He did not, for instance, tell me, “A boy’s best friend is his mother,” which could have given me a glimpse of the Bates motel hell, ahimsa version, that my life would gradually transform into.

Before that first meeting, I was concerned if he would be as good looking in person as he was in the photographs his parents shared with us. Was his English good, without a thick, off-putting Tamil accent. Did these frivolous concerns take away my attention from a deeper understanding of the person he was?

In the early years of our marriage, I would often tease Shravan, call him a mama’s boy, and he would laugh and retort with, “that was before our marriage.” Implying he was all mine now. I would be flattered, and laugh along with him, completely charmed. I am not laughing now.

It’s strange to recall how perfectly fine I was with an arranged marriage. I knew so many girls who considered it an outdated system. Was it conditioning through my mother’s horror stories of girls who married men of their choice and ended up dead or distraught? I did not question her about all the girls who got into arranged marriages that ended tragically. In fact, girls who get married seem to frequently end up dead or distraught, the latter more than the former. Silver lining and all that crap.

Or was it just me not wanting to take on the burden, the responsibility of choosing the right man all on my own?

“We will find a good, well-qualified boy for you,” amma would say. What exactly did well-qualified even mean? Appa and amma seemed very clear about what they were looking for. Biodatas were screened carefully. Post-graduates only. Preferably B Tech and MBA. Or MS. Preferably, the boy’s father should hold or have retired from a central government or at least a state government job. Ideally, a small family of just one or two siblings. Preferably and ideally was used a lot, hinting at a willingness to compromise. I was advised to be prepared to adjust. “The perfect boy does not grow on trees,” amma was fond of saying.

What did the right boy mean to me? I doubt I was thinking beyond looks and career prospects and the city the prospective groom was living in. Only Bangalore or Chennai. Or Abroad, capital A. But not ‘Gulf’, preferably. Europe or Australia was acceptable. No small towns or villages. No joint families with the risk of bossy in-laws and a lack of privacy.

I was 21, and completely sheltered. Did I consider emotional compatibility? I doubt it. We were cogs in the machinery. The elders in the family, uncles and aunts of whom there were far too many, would say, “Make sure girls finish their higher education by 22. Get them married before 25. Encourage them to have a baby or two before 30. Guide them, train them well.”

So, they are programmed to guide and train their children into the EXACT SAME PATH was left unsaid.

Yes, I followed the path. Worked for a paltry two years. High school teacher. A profession suitable for girls from good families.

The phrase ‘good family’ was bandied about much, in English, in the marriage market. All the classifieds in the national newspapers looked for professionally qualified grooms, 5’ 8” to 6 ft., from a ‘good family’, or well-educated, fair skinned brides from a ‘good family’, followed by the mandatory community specifications, of course — Iyer/ Syrian Christian/ Jain/ Jat/ Reddy etc. etc.

Horoscopes were matched fervently. Properly aligned stars promised a match made in heaven.

***

After our wedding, Shravan and I lived on our own. With frequent visits to and from the in-laws. I was aware of my mother-in-law’s constant supervision, in person and over phone, to ensure I was shaping up well. A good daughter-in-law.

I hate the word good. What a bland, annoying, meaningless, shitty word.

I gave birth to a son and a daughter with the proper three years’ gap, a living example of the slogans in family planning PSAs telecast by the government.

Hum do, hamare do!

khushhal pariwar ka mantar, do baccho mein teen saal ka antar!

Hints were dropped by my mother-in-law. How important it is for children to be cared for personally by their mother, especially in their early years. There is no substitute for maternal love, she would often say.

It was surprisingly easy for me to quit my job.

***

Shravan’s attachment to his mother was charming at first. He would talk to her for an hour on the phone every day, apprising her of his day. I thought it was nice, how homely he was. There were a few clues here and there. An absolute lack of boundaries.

He would joke with her, “Mama I am still your baby. Why don’t you breastfeed me anymore?”

She would laugh and respond playfully. “You are married now, go ask your wife.”

He would rejoin with the punchline. “How can I get a mother’s love from a wife?”

I wished there was a manual for marriage, the kind that comes with ovens and washing machines. Troubleshooting guide: what to do when an awkward problem crops up in your relationship. Step one.

I finally opened up to him a couple of years into our marriage, bluntly, how I found this kind of borderline sexual banter unpleasant. He reacted with anger. “How selfish can you be? If you are insecure about the pure relationship between a mother and son, shame on you.” I felt almost guilty.

I came across the term ‘enmeshment’ years later in an article on attachment styles. A woman had shared her experience, a long term marriage to a man from an emotionally enmeshed family, in the comments section and it read like a stalker’s chronicle of my life.

He toned it down a bit after that conversation. I was relieved. At least, we don’t live with the in-laws, I consoled myself often.

And so, we chugged along, slowly over potholes and speed breakers, always on the verge of a breakdown but somehow inching forward. It helped that he was a devoted father. My maid Manjula, who worked in our house for eight years, had only good things to say about him. “Doesn’t smoke, doesn’t drink, doesn’t womanise, helps with household chores, helps take care of the kids. You are lucky, sir is not like our men who drink and come home to beat us up, and for food and sex,” she told me once.

Whenever we travelled to Erode to my in-laws’ house, I was on tenterhooks. I tried too hard in those early years. Wake up early, be helpful in the kitchen, wear only traditional attire, saree or long kurta with dupatta, a smidge of kumkum on the forehead, make small-talk, be cheerful, look docile. I could create a PowerPoint presentation on ‘how to be the ideal daughter-in-law’ in my sleep.

Once, we were to travel to Erode for Shravan’s cousin’s wedding. I contracted a viral infection just before the journey. Shravan sponged my forehead, cleaned my vomit, made me hot kanji with a dollop of ghee, woke me up on time for my medicines. But he did not offer to cancel the trip. Not once. Because he could not bear disappointing his mother, who would be waiting to meet us. So, we travelled, and I threw up at the airport and I sat through the wedding, smiling at relatives, feeling sick, feeling hurt.

My needs, my feelings thus kept dying a quiet death, an expected but unsung sacrifice, flung into the gaping maw of the altar to his mother.

I tried to convince myself I was overreacting. My expectations were too high. I had no reason to be unhappy. I only had to open the newspaper to be reminded of my privilege. Rapes, gang rapes, acid attacks, dowry killings, honour killings. I was an empowered woman, who was safe in her house. I could eat what I wanted, wear what I wanted, except for those occasions when my in-laws were visiting. Then I had to cook according to their preferences and dress for their approval. These little adjustments are a part of everyone’s life.

I would compulsively count my blessings and when I got tired of counting them, I would allow myself to wallow, to revel in an abundance of disappointments.

My best friend from college, Anna, who was the only one with an inkling of the state of my marriage, asked me once, “Are you sure it’s really such a big deal? You don’t even live in a joint family.”

This was my biggest fear. Opening up to someone and being told that I was being unreasonable. I explained to her, “Imagine Shravan is inside a locked room. His mother is there with him. His father and his brother too. I am outside the room. I keep knocking on the door, asking to be let in. He doesn’t open the door, not because he is rude or cruel, but because he is happy, probably engrossed in an interesting conversation with them, and he does not hear me. At some point, after days, months, years, I stop knocking. He does not notice that as well. That I have stopped knocking.”

Anna looked at me with such pity that I stopped broaching my marital issues with her again.

And then she died. My mother-in-law, his mother. She had been unwell. It was thirteen years into my marriage.

She was then promoted to a goddess; she became The Mother.

The benevolent face of The Mother graced our puja altar. Her smiling face took up permanent residence as the display photo of her son’s messaging app, and there she stayed, month after month after month, year after year after year.

Shravan became a shadow of his former self. Like a wilting sunflower on a bleak, cloudy day. As if his will to live was leached off him, like he had nothing good left in his life anymore. Her favourite ghazals played in our home every day. Some days, he would spend hours looking at her photos. He started writing a daily note to her. Letters that could never be sent. The afterlife does not come under the dominion of the Indian Postal Service.

So many crutches for someone so limp with grief.

I vacillated between feelings of violent disgust and deep compassion for this man. How tough it must be to be like white paper, without desires of one’s own, dependent on another for streaks of vibrancy, for colour.

Conversations with him became desultory. I would bring up The Mother myself, recall the taste of her sambar, remind him how she would sing to Aarav and Ankie when they were babies. His eyes would become brighter then, his face would transform, become animated. I would get to see a genuine smile on his face.

I knew I had to escape this crypt where the dead were more alive than the living.

I enrolled in the master’s course I had discontinued a decade and two children earlier.

I finally made peace with The Mother. I had always believed she encouraged Shravan by coddling him, by constantly whispering her expectations in his ear. But now, I realised I had conveniently diminished Shravan’s free will in my thoughts, making her the scapegoat. She seemed like a tree which had lived its life well, fallen with grace. I had got to know her well enough over the years, to recognise she was capable of dealing with loss and grief better than her middle-aged son was handling his bereavement.

Can you blame a tree if a creeper sprouts from its seed, due to some anomaly of nature, and wraps around its trunk? Can you even blame the creeper that is left to flounder once the tree is gone?

Did his parents doom him by naming him after the mythical Shravan, blessed (cursed) to carry his blind parents on his shoulders till Kashi, the town that symbolises moksha. A subtle sales pitch. Suffer for your parents, and attain your rightful place in heaven.

***

I attended seven job interviews.

Each interviewer would ask, in an identical puzzled tone, as if they practised it together, “There seems to be a long gap in your resume. Why is that?”

Embarrassed, I would compose interesting replies in my mind. I was on a hot air balloon ride in Tunisia, when I fell and fractured my spine, leaving me in a coma for seven years. I was a RAW operative, living deep undercover in Karachi. I was protesting against the digging of oil rigs in Antarctica, to save penguins.

But I was taught to be a good girl. Amma always said, “Never do anything that will make your appa ashamed.”

So, I would reply, “I took a sabbatical to care for my young children.” The panellists would always look away for a moment, in disappointment, like I personally failed them, and then nod with an understanding expression.

I cleared the eighth interview and started teaching again. Classrooms and staffrooms and grading papers became a part of my routine once more.

I made sure I spoke to my children about a future which did not feature me. Learn to cook, to do your laundry, to start a bank account, to pay bills, so you can cope with living on your own, I would say. I avoided the oft repeated refrain of many parents, how they would be my support system in my old age. How it is the duty of a child to care for their aging parents.

When I die, I hope they will not sigh and cry, swoon and moan. I wish the part of my DNA that resides in them, lives on in their laughter. Maybe I would wake for a moment in the nothingness of ether and catch a glimpse of their joy, like sparks from a distant bonfire on a dark, dark night. Who needs tearful eulogies? I pray they forget me. Not completely, no. Just enough, to move on, to live their lives to the fullest.

In the meantime, my slow cooker escape plan takes shape.

It’s bizarre, I know. Like setting an alarm for ten years later.

By the time my son leaves for college, I have a fair amount saved in my bank account.

A month before my daughter is to leave for college, I apply for a teaching job at a boarding school, far away, two thousand kilometres away, in a hill town. I am worried they are looking for someone younger, not an almost fifty-year-old woman.

Two weeks after my daughter leaves, I pack my suitcase. I am travelling by train, taking my time to reach the school, a week before the start of the new term.

Shravan paces in the bedroom beside me, upset and angry in turns.

“I am getting old, have you thought of that?” he asks. “If I fall ill, who will be there to make me a cup of tea or some gruel?”

I consider not replying. The kinder option.

For a long time, I had disliked the girl I was once. Naïve, silly, sensitive, impractical.

I had killed her. Replaced her with what I believed was a better version.

Like a quaint cottage, that is pulled down, its rafters unceremoniously dumped to be used as kindling, replaced with a gleaming concrete and glass structure, I rebuilt myself. Fireproof. Water proof. Hurt proof.

I allow myself to finally mourn for that girl who is dead. No, not dead, just upcycled. The one who had expected a lover, a companion, a confidant, a cheerleader but had been left with a shadow, sighing like the wind, pining away for a dead parent. I remember the loneliness, the wretched loneliness.

I stop packing and look at this man, with whom I have shared most of my life. I search for the right words to respond to him.

I had asked him over the phone, a few days after both of us, and our families, first met, “Why did you say yes? What did you like about me?” I had hoped to be flattered about my bright eyes or wavy hair, admired for my intelligence or my sense of humour. Instead, he had replied, “When I saw you first, I immediately turned and looked at my mom. I could see that she liked you. That’s why I said yes.”

I dip into the reservoir of resentment, secreted away in the dank, mouldy recesses of my heart.

I look into his eyes, and utter the words I could have voiced a thousand times, but hadn’t ever in twenty-four years.

I reply, “Go ask your mother.”

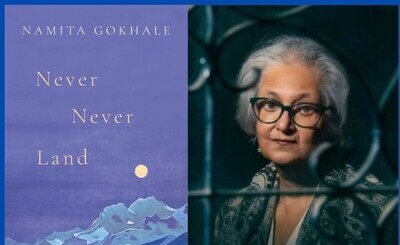

First published in The Best Asian Short Stories 2023 (Kitaab, Singapore)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated