“…and the last puff of the day brought from the unseen villages the scent of damp wood-smoke, hot cakes, dripping undergrowth, and rotting pine cones. That is the true smell of the Himalayas, and once it creeps into the blood of a man, that man will at the last, forgetting all else, return to the hills to die.” — Rudyard Kipling

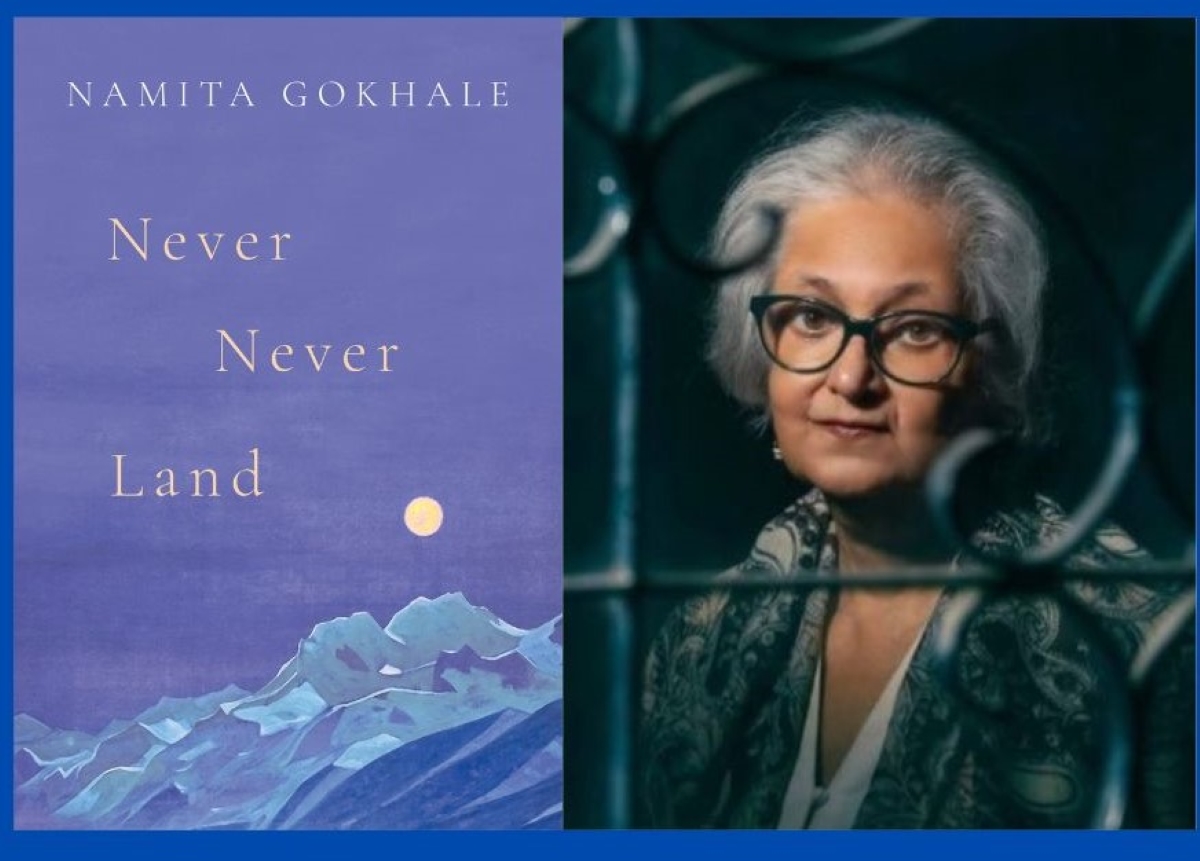

Set in the beautiful Himalayan region of Kumaon, Namita Gokhale’s latest novel, Never Never Land, follows Iti Arya, a lonely, middle-aged, convent-educated freelance editor, who feels lost and disillusioned in her big city life. She proofreads and copy-edits manuscripts and takes on small writing gigs as they come. Despite her aspirations to write a novel of her own, she finds it hard to make a start.

Iti feels disoriented from her school friends (“trad wives living trad lives”), with whom she shares a WhatsApp group where they constantly babble about their children, holidays, and other topics she can’t relate to. “Their lives stink of safety and leisure and the security nets of family,” she explains. Ironically, despite this disconnect, they are all she has — her link to herself, her virtual family, and her mirror to her own identity.

Gokhale, a writer and editor, has written 23 books of fiction and non-fiction; her work spans various genres, including novels, short stories, Himalayan studies, mythology and books for young readers. She is also the co-founder and co-director of the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF). She belongs to Uttarakhand, and makes her views on city life quite explicit at the very start of the novel. Through her protagonist, she describes the Delhi monsoon as a “betrayal”. “The sky is a grey rag, and the air toxic and always muggy,” reads the novel’s opening line. Moving to Gurgaon (now Gurugram) further multiplies the scars of the betrayal, she writes, referring to it as “just a dusty, sludgy, vertical slum”.

In her childhood, Iti had imagined the mountains circling her like wise old men with long beards, speaking to her and comforting her. And so, she dreams one night of the mountains — with their “jagged pines and blue skies and the whispering winds”. The next morning, she packs her belongings and leaves her rented flat in Gurgaon for The Dacha, a remote cottage in the Himalayas where she had spent some of the happiest years of her childhood. In a sense, she returns to “never never land”, a term used in several fairy tales, referring to an imaginary, ideal place or situation. “Sometimes we have to retreat to return,” Gokhale muses.

At The Dacha, she begins to live with her two beloved grandmothers whom she was meeting after almost a decade. Ninety-something Badi Amma and hundred-and-two-year-old Rosinka Paul Singh are both Pahari women, “strong as the mountains” — “weathered old women, so different from each other, and yet so alike”. Added to the trio is also a mysterious young girl called Nina who may be Iti’s sister.

Almost instantly, the hills begin to lift her spirits. “The sunlight, the coffee, the morning air — these things made me smile,” she states. With hardly any mobile network, email or social media to distract her in the hills, Iti finds that the more she disconnects with her devices, she becomes more and more connected with nature and her own self. The haunting imagery of the rain-sodden mountains that Gokhale draws up is almost meditative: “Motes of dust danced in the clear sunlight. A magpie swooped down, then retreated. Its harsh chatter broke the quiet of the afternoon as it settled on a low branch of the silver oak that edged the garden”.

Iti also begins to journal her thoughts in a diary. In ‘A Litany of Lost Lovers’, she recalls some of her short, fleeting romances with a range of men, which never went anywhere. Over the years, she gave up hope on the dream of coupledom, and figured that she didn’t really need a man in her life to complete her, and was all right alone on her own. “It’s a giant step for every woman when she takes it,” she writes.

Simultaneously, she also embarks on an archiving project in which she begins to chronicle the memories of her two eternal grandmothers. Along the way, Iti also learns about some complicated issues of her family history and inheritance, such as the mystery behind Nina, who is supposedly her cousin. She also discovers the vulnerability and foolishness of the youth, who are often left hurt easily in their spontaneity and inexperience. Nina impulsively runs away with an artist, taking along with her some expensive paintings from the house. After being trapped in a landslide during the rain and storm, she is rescued with great difficulty. Realising her mistake, she returns to the house.

Iti shares her thoughts on her distant and complex relationship with her mother whom she struggled to love. Her feelings for her oscillated between “indifference, passive hatred, active hatred, and a yearning to be loved by her.” Burdened with duties and responsibilities, she analyses that her mother lacked will and a sense of self, which made her seem rigid and inflexible. When her mother suddenly dies in Bangalore, it brings Iti a sense of closure.

At 170 pages, the novel is divided into 16 short, concise chapters, making it a breezy and pleasant read. Overall, the book is about female friendship, love, the ageing of the body, the mind and memory, and loneliness. Though it first appears to be about Iti Arya, when one looks a little deeper, it could very well be the story of you or me. As Gokhale rightly comments, “we all walk a thin line.”

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

Beautifully written, Thank you for sharing.https://fathimajilna.com/

Fathima jilna

Jul 22, 2024 at 06:19