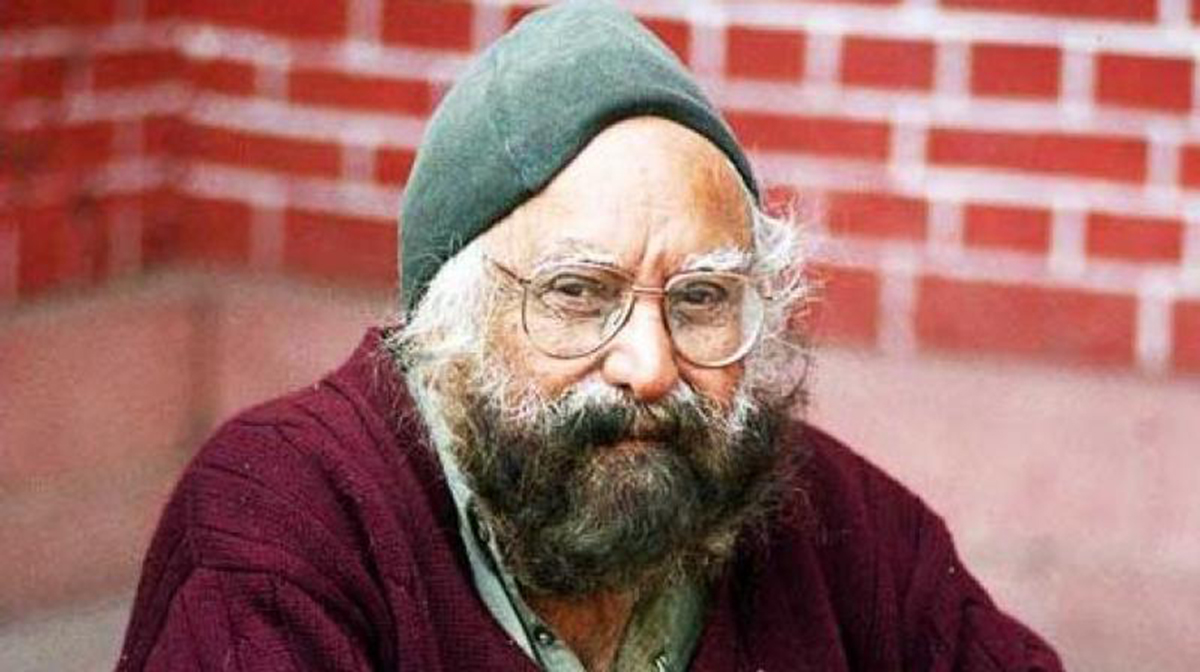

Khushwant Singh

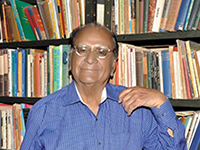

Snatches from a rare and unpublished conversation with Khushwant Singh (1915-2014) by Professor Shiv K Kumar (1921-2017), poet, playwright, novelist and short story writer. Before his death, Professor Kumar had graciously given The Punch Magazine the permission to publish this.

Khushwant Singh (August 15, 1915-March 20, 2014) was born in Hadali, a town of Khushab district in Punjab, in an affluent Sikh family. His father, Sir Sobha Singh, was a prominent builder and contractor known for building most of Government of India secretariat buildings. He had his schooling in Lahore at Modem School and graduated there from Government College and St. Stephen’s College in Delhi. Later he went to England and studied at King’s College before reading for the bar at the Inner Temple.

On his return to India, he took to journalism as his career and had such important assignments as editor of Yojana, an Indian government journal and later became editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India, an allied magazine of The Times of India, Bombay. He then took over as editor of The National Herald and the Hindustan Times. But he is primarily known for his popular column “With Malice towards One and All”.

Khushwant Singh has published six collections of short stories titled The Mark of Vishnu and Other Stories, The Voice of God and Other Stories, A Bride for the Sahib and Other Stories, Black Jasmine, The Collected Stories and The Portrait of a Lady. Among his novels may be mentioned — Train to Pakistan (his most popular novel), I Shall Not Hear the Nightingale, Delhi: A Novel, The Company of Women and Burial at the Sea.

Khushwant Singh is also known as a distinguished historian whose book History of the Sikhs is universally applauded. Among his other historical, social and political publications may be mentioned Ranjit Singh: The Maharajah of the Punjab, Ghadar 1915: India’s first armed revolution, Women and Men in My Life, Why I Supported the Emergency: Essays and Profiles, The Sunset Club, etc ..

As a translator, he is known for his translation of Iqbal’s poem Shikwa. Singh was one of the most controversial writers in India who was recognised for his playful irony, pungent sarcasm and irrepressible integrity.

In 1977, a little before Christmas, I was invited by Nissim Ezekiel, a leading Indian English poet and a lecturer at the University of Bombay to give a poetry reading at his university. After the session, one of his colleagues asked me if I’d like to meet Khushwant Singh, a fellow Punjabi writer, who was then editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India. Since I had read several of Khushwant Singh’s books and admired his forthright transparency and boldness as a journalist and writer, I replied that I’d be delighted to meet him.

Next afternoon I found myself at The Times of India building on Dadabhai Naoroji Road, with Ezekiel’s colleague, who took me to the editor’s cabin. There sat behind a desk, loaded with piles of books and manuscripts, a hulky Sardar, with a light pink turban on his head and a steel kara on his wrist. Since it was already winter, he was wearing a light brown pullover with a couple of chinks showing near his left breast. Without standing up, he put out his hand across the table for a friendly shake.

“Please sit down, Dr Kumar,” he said, his eyes lingering on my face. Would you care to have some coffee, please?”

“Thank you, Sardar Sahib,” I said.

“Just call me Khushwant,” he said, smiling. “There should be no formality between two Punjabis meeting in a foreign territory.” He beamed, “What part of the Punjab are you from?”

“From Lahore, I responded.

“Ah, that’s my native city. That’s where I had my schooling and college education, before I went to London to do my bar-at-law.” Then after a pause, he resumed, “Since my Punjabi is getting rusty let me refurbish it

by unloading some of it on you.” Then turning to Joshi he added, “I hope you wouldn’t mind us being somewhat clannish.”

My companion said, “Not at all. Go ahead. In fact, I should like to hear this language which sounds so virile and punchy.”

Just a few words later, Khushwant returned to English, which he spoke with a palpable Punjabi accent. I recalled how he had once used a stout Punjabi Sikh, holding a glass of sparkling beer in his right-hand, as the title cover of one of his Weekly issues. It carried a sub-title: “Punjab, No 1.” Khushwant himself looked a typical Punjabi. In spite of his stay in England, he stuck to his turban and Punjabi dress. I had already noticed a kara on his right wrist, and I imagine that he also wore a kucch under his trousers, because the Sikh religion directed every Sikh to wear Kucch, kara and kirpan. Kirpan was a sword carried by every Sikh traditionally, because Sikhism was born as a revolutionary sect to fight against all invaders, particularly the British colonialists. I now felt that I should say something ingratiating to him so that he may feel at ease with himself. I started off saying, “I don’t wish to embarrass you, Khushwant, but I like all your writings, particularly your classic book on the history of the Sikhs. Interjecting, he said, “Well, that should remain my magnum opus. I am a journalist and I have published some novels of course, but fiction is not my first love.”

“No, please don’t say that. You are the author of that classic novel, Train to Pakistan, which will always remain a bestseller.”

“I must say that I did enjoy writing that book. You know, every Punjabi writer has to get Partition out of his system sooner or later. I lost several friends, during those traumatic months of 1947, who were mercilessly butchered by the Muslims back in Pakistan.” He paused. “But I wouldn’t exonerate my fellow Hindus and Sikhs from the brutality they unleashed on the Muslims in India who couldn’t migrate to Pakistan in time. You know, I think that human beings often behave worse than animals. I have enjoyed dogfights and cockfights. But these animals and birds don’t go beyond certain limits. Man, on the contrary, can be viciously brutal.” He took a deep breath before adding, “Pardon me, if I now sound like a pacifist. All that I wish to say is that there is still so much common between Pakistanis and those refugees who migrated to Delhi and other places in India. We inherit the same culture, wear the same dress, and speak the same language, so why should we fly at each other’s throats?”

“I quite agree with all that you have said,” I responded. “My family also had to pass through fire during Partition. We left everything behind in Lahore, and had to start from scratch in Delhi.”

“Delhi? Sitting here in Bombay I miss that city although it’s getting insufferably crowded and polluted. As soon as I complete my tenure as editor of the Weekly, I hope to get back to Delhi which has now become my hometown.”

Smiling, I quipped, “Of course, everyone knows that your father was one of the architects of New Delhi. Delhi owes so much architecturally to Lutyens and your father.” Then I added with a smirk on my face, “I imagine that since you are a money bag, you don’t have to take up any job.”

“No, I love writing. I would be editor to any magazine just for the fun of pushing my pen on paper.” Then, with an impish smile on his face, he added, “You know, I don’t mind a glass of whisky — good Scotch, of course. I always relish having a free drink anywhere, any time. But I’m not a boozer. Whenever I’m invited to a party, I stop after a couple of drinks and then when everybody else is deep in his cups, I prefer to slip away.”

“That shows you are a very disciplined man,” I complimented him.

“What kind of discipline would you associate with a man who enjoys a beautiful face anywhere, any time? Recently I published a story in the London magazine, “The Bottom-Pincher”, which brought me barbs from several friends and readers. You know the story was based on my personal experience. I do enjoy pinching women’s bottoms whenever I can as I make my way through a crowd.”

“One of the traits I admire in you most is your transparency, your lethal forthrightness. One of your stories that I’ve read over and over again is ‘The Rape’ which you included in your first collection of short stories, The Mark of Vishnu. It’s a delightful piece of writing. The twist at the end, where Banto after filing a case against her rapist admits, in the course of hearing that she did enjoy the act. Am I right that Confucius also said something similar —that if a woman cannot protect herself against a rapist, let her enjoy it.”

He burst into a guffaw. “There’s a fellow Punjabi! You know, this is what sets us apart from any other region in the country.”

Then, feeling a little conscious, he turned to my companion; “I hope you don’t mind us both glorifying our Punjabi culture. We are Epicureans in a sense. We enjoy eating, dressing, and boozing. That’s why we haven’t produced many intellectuals in that part of India.”

Turning again to my companion, he added, “You may take it as a compliment to Maharastrians, Bengalis, Tamilians and Gujaratis.”

This was the beginning of an “affair” between a writer and an editor who was not only a novelist but also a lover of poetry. He published several of my poems in the Weekly, but I was particularly touched by his letter - of appreciation about a story that he had accepted for his magazine, titled “Beyond Love”. It was a story about a woman who was deeply in love with her husband but who lost him in an accident. In a state of hallucination, she imagines that her husband comes back to her in the middle of the night and makes love to her. But, in fact, the man who walked into her house was her husband’s closest friend who had completely empathized with the anguish of his friend’s widow. When in the darkness of the night, she hallucinates, ‘I knew you were not dead and that you’d come to me soon.” He surrendered himself, most painfully, in bed with her, just to make her feel that her illusion was a reality.

But next morning when he showed up at the house to sign certain legal papers, she realised that the man who came to her was not her husband. Both man and woman understood what they had done, but not a word was uttered about it. This was an act that went “beyond love”.

Khushwant Singh used another of my stories titled “The Foreigner” in an anthology that he compiled and edited for HarperCollins. A couple of years later, I ran into him in a bookshop in Connaught Place in Delhi. I was browsing amongst books at Rama Krishna bookstore when he walked in with a beautiful young woman. I was holding Mulk Raj Anand’s novel, The Untouchable, which I had of course read earlier a couple of times. As he looked at the title, he said, “Tell me what you think about Mulk.”

I responded, “He was not a creative writer in any real sense, but he was an interesting storyteller who wrote about the weak and the downtrodden.”

“I appreciate your comment,” he said. “Is a novelist supposed to be a propagandist? He was a writer who was selling his Marxism in everything he wrote. Frankly speaking, I never liked him.”

I realised that though he was a Punjabi writer himself, he couldn’t stand Mulk. Was it jealousy, rivalry or some kind of animosity?

Switching to another track in our conversation, Khushwant said, “Nissim Ezekiel has just completed two years of editing my page in The Illustrated Weekly of India which appears every month. under the caption “Poetry of the Month”. Since I like your poetry, would you like to take over this page for the Weekly?”

“I’d love to do it for you.”

“Then I’ll send you a pile of poems waiting on my desk, for you to select six poems for the next issue. Remember, you’ll receive about a couple of thousand poems every week to choose from. As editor of the Weekly, I notice that every third Indian writes poetry.” Here was Khushwant with his customary fling at all those who wanted to be known as poets.

The Weekly gave me an opportunity to correspond with him from time to time. I telephoned him one morning in Delhi to say that I should like to spend a little time with him in his apartment which was located in the Sujan Singh Park, near hotel Ambassador. Genially, he invited me to tea over the weekend. As I walked into his complex of apartments, I saw a tent pitched outside on the lawn, and some armed policemen patrolling all around. I was stopped by a guardsman who asked for my identity. “Shiv Kumar is my name and I have an appointment with him.” He looked at a piece of paper in his hand and said, “He’s waiting for you.”

I knocked at his door, and was called in. There was Sardar sitting on the sofa flanked on either side by two beautiful women.

I asked him, “Why this patrolling outside Khushwant?”

“You should have read in the papers that I’ve been threatened by the Khalsa terrorists in the Punjab for writing a strong column against the violence unleashed by these criminals. When I brought this to the notice of the Government of India, it arranged for these security guards. Now I feel a prisoner in my own house. I don’t want anyone protecting me when I can take care of myself.”

(Then, gesturing me into a chair next to him, he added)?

“Let’s forget the terrorist and the policemen. What do you think of these two charmers?”

“Beautiful.”

“You see I’m never alone,.” he smiled.

“What can I offer you? How about some tea with honey?”

As I said yes, he snapped his fingers and called out, “Where are my slaves?” A minute later, appeared his wife, smiling.

“You see, Shiv Kumar, I fantasize that I’m some kind of Moghul emperor with a retinue of servants. But all I have is my beloved wife to take care of me.”

I broke into a peal of laughter. He was a man with a genuine sense of humour.

“What can I do for you? I guess you have come to see me about something. Let’s not waste any time. What can I do for you?”

I handed him a copy of my novel, Nude Before God, saying, “You may see that this novel has already been published by Vanguard Press, New York. But since you are a consulting editor to Penguin Books, would you, please, consider recommending it to your publishers —that’s, if you really like it. I know that you are not the kind of man who would compromise his integrity.”

His face broadened into a smile as he said, “It seems to be very elegantly produced, but let me have a look at it. Would you give me a couple of days?”

Three days later, I had a call from Khushwant Singh, saying, “You know the day you gave me your novel to read, I sat up all night because I couldn’t put it down. It’s a piece of fiction which I would call unputdownable.” Then probing my face, he said, “How were you able to get Graham Greene to read it because he is so inaccessible.”

“But miracles do happen,” I said. “I just wrote him a letter and he agreed to read the manuscript.”

“Lucky man!” he said. “In any case, I’ve already talked to David Davidar, Penguin’s Chief Editor, about your novel, recommending it very strongly. You know he dare not turn down my recommendation.”

There was the great Sardar who always spoke like a feudal lord. “Wait a minute. Wasn’t Graham Greene sometimes indiscriminate in his patronage? Look what he said about R. K. Narayan’s novel, The Bachelor of Arts.”

The novel was indeed published by Penguin Books as one of the six titles brought out by Penguin Books which had just established its offices in New Delhi. Two of the other titles that Penguin had published were Unveiling Woman by Anees Jung and Pupul Jayakar’s biography of J. Krishnamurti. The book release function was held at a five-star hotel with a large crowd of people invited. Of course, most of them came more for the cocktails than for the book launch. Chairman of Penguin Books, London, Peter Mayer had flown in from London to participate in the function which was to be presided over by P. V. Narasimharao, the external affairs minister who had acquired the reputation of being a lover of literature. As I sat with David Davidar, Peter Mayer and a couple of other dignitaries, I saw Khushwant Singh walking in, flanked by two charming women —different faces each time, of course. As he took his seat next to me, he whispered into my ears, “How do you find them?”

“Charming, of course.” Then, I quipped, “But then you are a charmer too — not a snake charmer but a ladies’ man.”

He flashed his customary broad smile, and helped himself to a glass of whisky, whispering into my ears again, “Nothing tastes more exciting than a free drink.”

But irrepressibly candid as he always was, if he liked Nude Before God, he tore into pieces my novel Infatuation which he thought was written hastily, poorly conceived and hastily written. But while he said unkind things about my novel in his column, “This Above All” that he ran for The Tribune, he was also very generous in his tribute about me as a poet in the same column. Saying that I should devote more time to poetry, he said, “Shiv Kumar is a gifted poet. This gift is given by the Gods to very few people.” I felt that his denunciation of my Infatuation was more than amply compensated by his glowing appreciation of my poetry.

Indeed, Khushwant Singh is known as a historian, journalist and fiction writer, but his heart lay with poetry. He loved Urdu poetry and amongst his favourite poets are Faiz Ahmed Faiz, whom he knew personally, Mirza Ghalib, Mir Taqi Mir, Iqbal, Dagh and Momin.

I somehow brought myself to ask him, “Why haven’t you tried your hand at verse writing? Surely, you must have scribbled some verses in your youth because you’ve been a lover of beautiful women all your life?”

“No, I’ve left verse writing to the others —friends, like you. But I like listening to ghazals and reading poetry, particularly Urdu.”

“Yes, I do remember reading your column, years ago, about Jagjit Singh whom you heard at a private party. In fact, he owns his career as a maestro of ghazal-singing to you.”

“Indeed, I was thrilled to hear him sing at this private party. He was a stranger in town, lost in a vast city like Bombay, where seekers of stardom keep pouring in almost daily. But here was a young man who deserved appreciation from all lovers of ghazals.”

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

THUMBS.jpg)