The winners (from left) of Sushila Devi Literature Award, the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature and the JCB Prize 2019

I have been sitting on various literary juries for the last two or three decades but this year it all came together with the kind of fortuitous intensity that obliges one to stop and reflect on what exactly one is up to and what it’s all about anyhow. Why do we award literary prizes at all? What is their purpose and function?

The year 2019 turned out for me to be a year of literary prizes. Not that I won any — and it would have been scandalous if I had for I haven’t written a line of verse or fiction since age 17, and that was over 50 years ago.

Rather, I helped give away prizes. I sat on the juries of three of our highly regarded but very different kinds of awards — the Sahitya Akademi prize, the Jnanpith award, and the DSC prize for which I was chair of the jury. As a member of the advisory council of another big prize, the JCB, I attended the dinner at Jaipur where the prize was announced and awarded, and interacted there with the jury and the short-listed authors. I have been sitting on various literary juries for the last two or three decades but this year it all came together with the kind of fortuitous intensity that obliges one to stop and reflect on what exactly one is up to and what it’s all about anyhow.

What transpires among jurors is necessarily confidential, even post facto. But prizes have become such a salient feature of our literary scene, equalling if not eclipsing the ubiquitous litfests, that a general discussion of their place and importance in our literary ecosystem is not only desirable but necessary. In any case, in our information-hungry day and age, all organisations, including those that award literary prizes, have a website keen on telling all and publicising the prize. So, anyone can Google and instantly find out who were on the jury for a prize in any given year, which authors were longlisted and then shortlisted, and who eventually won. What remains to ask is what precisely the value and function of literary prizes is for authors and readers, what kind of factors go into deciding them, and why do we have them at all.

Origin of Literary Prizes

Literary prizes as we know them now are surprisingly new in form but the idea and the practice of rewarding worthy authors is clearly very old. There were oral and performative contests in ancient times in both Greece, where a laurel wreath was to be won, and in India where the gains were apparently more substantial. At a great yajna held by King Janaka in times immemorial at which sages from far and wide had gathered, it was announced that a disputation will be held alongside to determine who the wisest of all the assembled sages was, and the prize on offer was a thousand cows with five gold coins hanging from each horn. On seeing them, the great sage Yajnavalkya instantly asked a disciple to drive the cows home saying: I bow to whoever may be the wisest person here, but I want the cows. He was of course stopped — but that’s another story. (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad).

To cite two other instances of literary reward, the Hindi poet Rahim, known more formally in his capacity of Emperor Akbar’s star courtier, and commander-in-chief as Abdul Rahim Khan-e-Khana, was a generous patron of other poets and once when the poet Ganga composed a six-line verse with heavy mythological references in praise of Rahim the warrior, Rahim was so mighty pleased that he rewarded him on the spot with Rs 36 lakh. (I have read this little poem six times and will not give it more than 36 rupees). But the amount Rahim disbursed so promptly still comfortably exceeds any prize yet instituted in India, even without factoring in the inflation since c. 1600 AD.

In the eighteenth century, the Urdu poet Mir Taqi “Mir”, who is ranked next only to Ghalib, was once reciting a new ghazal to the nawab who was then his patron, while the nawab walked around in his garden and seemed more interested in watching the fish darting around in a fish-pond. When Mir said, “Huzoor, the next couplet begs for your tawajjoh (attention),” the nawab finally turned around, gave Mir a good hard look, and said, “If it deserves attention, it will gain attention.” Courtly patronage was a double-edged sword which could deal out honour and dishonour equally.

The popularity of the printed book and the democratic expansion of readership changed all that, and a best-selling book became its own reward as it continues to be even now. As for literary prizes, one of the earliest to be set upremains the big dad of them all, the Nobel in 1901. It provoked the French to set up in 1903 their own Prix Goncourt, which in turn promptly led to the setting up of Prix Femina in 1904 which has an all-female jury. An early prize set up in Hindi was the Mangala Prasad Puraskar in 1932 while the Ananda Puraskar in Bengali was started in 1958.

Competition, Comparison and Canon

All literary prizes have one thing in common, that they have each year only one winner — except when they flout rules as the Booker did this year. But this is a strange and even bizarre idea where literature is concerned. How can just one author among scores or hundreds be adjudged to be better than all the others when the works they produce are barely comparable? I have a suspicion that the idea of a single winner in literature comes to us from athletics and sports. In 1894, Pierre de Coubertin draws up a plan to revive the Olympic Games in a modern format which are first held in 1896. In 1895, Alfred Nobel has the idea to set up his prizes and these are first awarded in 1901.

But physical games, such as races and long or high jumps, can clearly and visibly produce a single winner, even if with the help of a photo finish image, because every competitor is asked to do exactly the same thing at the same time and it is for everyone a level playing field, so to say. They are all on the same track if not quite on the same page. But in writing poems or novels, each writer is on his/her own, even physically by himself, drawing on his own unique experience, imagination and artistry, and there is no common finishing line. In fact, the distinction of a writer often lies in just how unlike he is and his works are from every other author and their works. Preferring one author over another is thus like preferring apples over oranges or bananas, but even that is a bit of an understatement, for there have been more authors than there are kinds of fruit on the earth.

But this does not mean that authors cannot be compared with each other at all. There is indeed a whole discipline named Comparative Literature and those of us who practise and teach it know that all meaningful literary comparisons are based on two cardinal factors. One, that there should be sufficient “grounds of comparison” between the authors being compared, which clearly means that one cannot compare any author/book/period/ movement/style with any other arbitrarily. The other essential factor is that despite being called “comparison,” the process must never end in declaring one author to be better than another. A true comparison between two authors serves to illuminate each author and enhance our appreciation of him/her in a way that would not have been possible without juxtaposing just those two authors.

Thus, we have had running comparisons between eminent contemporaries who shared the same milieu, literary tradition, period or theme: Kalidasa and Bhavabhuti, Magh and Bharavi — or Shakespeare and Marlowe, Dryden and Pope, Dickens and Thackeray, Kipling and Forster, Eliot and Yeats, Heaney and Hughes — or Surdas and Tulsidas, Bihari and Dev, Nirala and Pant, Premchand and Jainendra, Agyey and Muktibodh — or Mir and Ghalib, Anis and Dabir, Sharar and Shararar, Firaq and Faiz. Connoisseurs of these literatures have spent countless delicious hours arguing the merits of each writer in these pairs in relation to the other.

Another comparable procedure has been to construct a canon of a literature, and here the field is naturally wider and the choices to be made less acute. Tagore has a delightful poem in which he wishes he had been born in Kalidasa’s opulently erotic times, and adds that with a little bit of luck he might even have become the tenth jewel (dasham ratna) at the court of King Vikramaditya, famed for the nine jewels, including Kalidasa who added lustre to his glorious reign.

In Hindi, a band of literary historians at the beginning of the twentieth century constructed their own canon of the nava-ratna or nine jewels of Hindi literature. But they had to face vociferous protests over the fact that they had left out Kabir, and they then brought in Kabir but retained the number at the hallowed nine by clubbing two poets who were brothers in just one slot. (These critics were themselves three brothers, and are now known just as the Mishra-bandhu!) After the emergence of race and gender as vital factors in literary evaluation, canons have in fact become as much of a contested site with regard to older writers (“dead white males,” or in the case of India perhaps dead Brahmin males) as literary prizes are with regard to writers still living and going strong.

Eligibility and Procedures

It may seem that all literary prizes may employ the same procedures and criteria for deciding the awards but this is not quite so. To speak only of the three prizes I helped judge this year, these criteria were radically different in each case and so were the jury procedures.

To begin with the Sahitya Akademi prize, it is the oldest pan-Indian literary prize in the country for it has been running since 1954, and it is also probably the prize most cherished by the writers themselves across the country. UR Ananthamurthy once told me with deep regret, just after he was elected the President of the Sahitya Akademi, that he would now never win the Akademi prize, and it rankled with him even after he had won the Jnanpith.

Some years ago, several protesting writers from different languages returned the prize, rather like little children who go running and crying to their mothers when in distress, even when they knew that the murders of the fellow writers they were protesting against was a law and order problem which the poor Akademi could do nothing about.

The Sahitya Akademi is the only organisation in India to award a prize for the best book in any genre in each one of 24 of our major languages, which is two languages more than the 22 listed in the Eighth Schedule of our Constitution. In fact, it has an award in each language not only for the best book overall but also for three other categories: for Translation (Anuvad Puraskar), for Young Writers (Yuva Puraskar), and for Children’s Books (Bal Puraskar). That is 96 awards every year, and each one is coveted and prized. I was this year asked to sit on the jury for children’s books, and I accepted despite my incompetence in the area for the vain reason that it enabled me to complete a personal Grand Slam, so to say, for I had been on the juries of the three other categories already.

Of the major prizes, the main Akademi award offers the least money (five thousand rupees in 1955; one lakh now). It considers books published not only over the previous one year but over the previous five years (so that the fifth jury can still atone for the sins of omission of the previous four), and it does not entertain submissions from authors or publishers. It has a set of experts to prepare a ground list, which another set of experts then screens and augments, and their recommendations are then collated by a third set of experts to arrive at a short list of around five to ten books. A jury of three members comes in only at this fourth and final stage to read and decide between these shortlisted books (which the Akademi now buys and provides them with copies of), at a meeting where the convenor acts as a largely silent non-voting member, for his role is only to see that the procedures are correctly and fairly followed. For example, the jurors must take up and discuss each shortlisted book and not pass over some in silence.

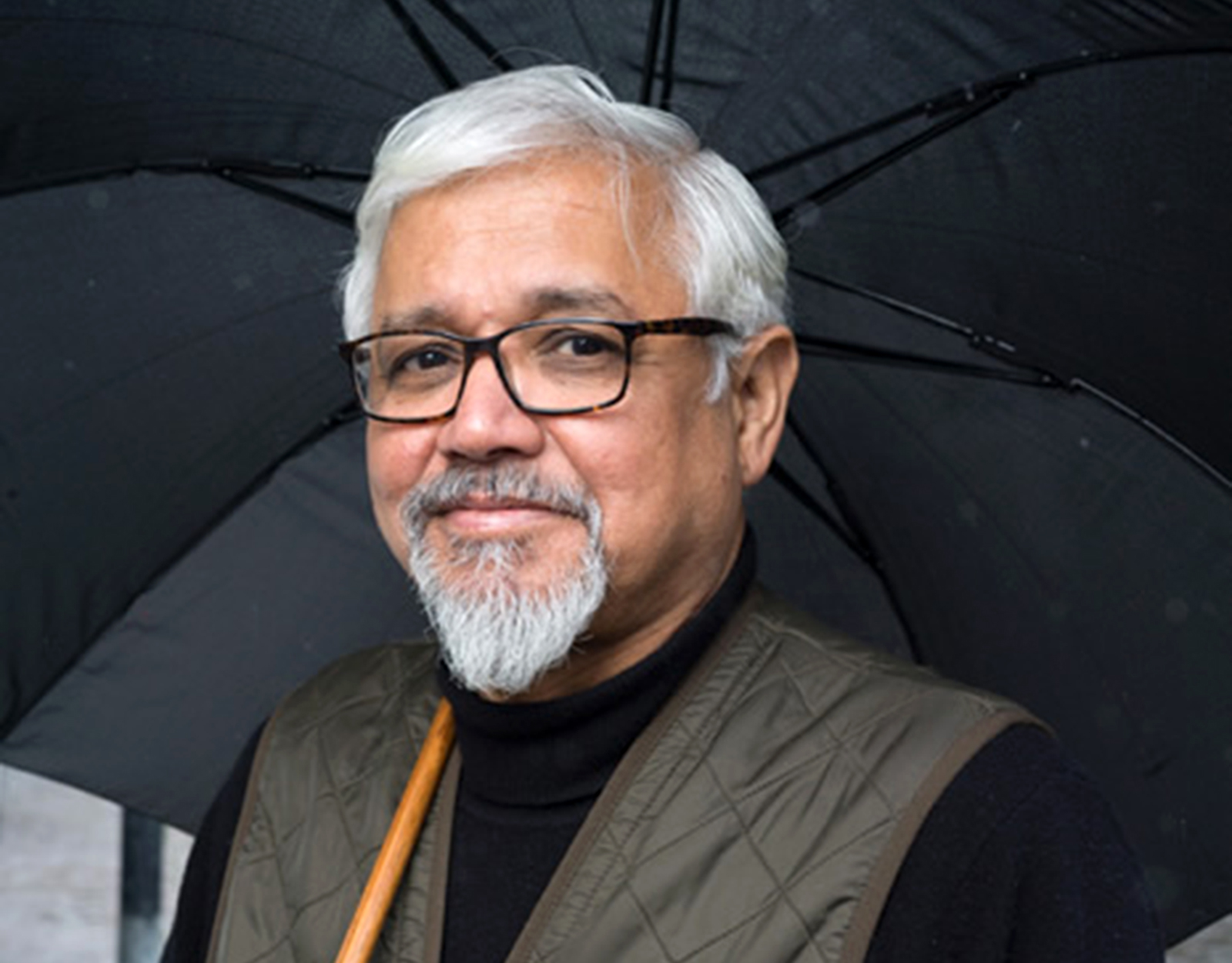

Amitav Ghosh. Photo: amitavghosh.com

Jnanpith is in effect a lifetime achievement award, and it helps to win it if the aspirant has a long enough life. The youngest winner so far has been Amitav Ghosh in 2018, the first writer ever in English to win it at 62. He cherished this prize so much that he instructed his publisher not to enter his new novel Gun Island for any prize anywhere, to offer tribute to the Jnanpith

The Jnanpith jury has an even wider writ and timeline for eligibility. This award (which carried the fabulous-sounding sum of Rs one lakh when it was started in 1965, which is currently pegged at Rs 11 lakh) is probably the ultimate award that all major writers in any Indian language covet as they approach the fulfilment of their careers. There is only one award each year for all the languages of India put together, so the competition is intense and the queue long. Nearly all recent winners have been in their eighties except for those who were in their nineties.

It is the last word in literary awards and goes to writers regarded in their own languages as the Grand Old Men (or Women) of literature. It is in effect a lifetime achievement award, and it helps to win it if the aspirant has a long enough life. The youngest winner so far has been Amitav Ghosh in 2018, the first writer ever in English to win it, who was then 62. Despite his global fame, he so cherished this prize that (as he told me at the dinner he hosted on the evening of the award), he instructed his publisher not to enter his new novel Gun Island for any prize anywhere, to offer respectful tribute, as it were, to the Jnanpith.

The jury of the Jnanpith award comprises eight to a dozen experts from some but not all languages, for each juror is expected to plead not for a particular language but to take a broad pan-Indian view. Advisory committees in the various languages send in one or two nominations each year with some details of the author, but other bodies and individuals too can send in nominations. There is no short list, nor are the jurors sent and required to read any books at all, for they are all assumed to be persons who are already widely knowledgeable in contemporary Indian literature. Often, they go not by works but by the wide reputation that the authors under consideration have already earned, and this prize thus can be said to run largely on reputation — in more senses than one. The winners over the past 65-odd years truly constitute a pan-Indian literary canon for the twentieth century and now the twenty-first. Nearly all the greats are there, for if they do not win it one year, they are likely to win it the next or the next — or the next.

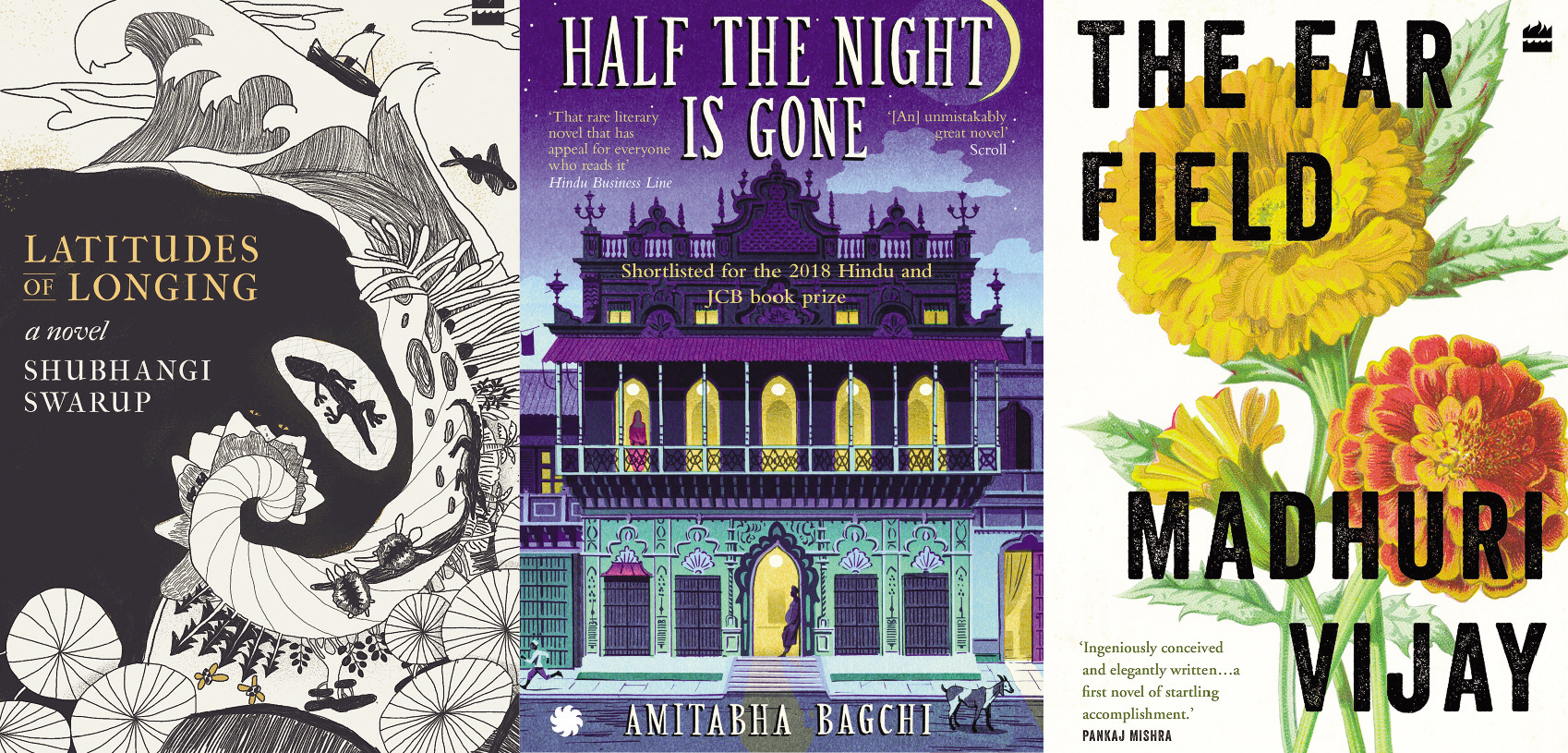

This marks a great contrast to the two more lucrative prizes established recently, the DSC ($25,000) which began in 2011, and the JCB (Rs 25 lakh) which was set up only in 2018. Both these prizes consider books only in English, including translations into English, and published within the previous 12 months. The eligibility span here is as fleeting as it is perennial in the Jnanpith. Several debut novels have been shortlisted for these prizes year after year and some have indeed won, and there is an Anglophone topical-presentist air about both these prizes. This can of course be described alternatively as being cutting-edge and state of the art. Each of these prizes is sponsored by a business house based in the UK, of which one is owned by an NRI family (the Narulas, for the DSC) and the other is British-owned (the Bamfords, for the JCB).

Thus, both the prizes can be looked upon as FDIs in the field of English writing in India, for even translations from the Indian languages serve to enrich English. One significant difference between the two is that the JCB is for Indian writers, including NRIs, while the DSC has a wider scope in considering writers from all the nine SAARC countries and indeed writers from anywhere in the world, so long as what they write about is South Asia.

The Judging Process: Anecdotal Glimpses

The judging of literary prizes is said, often in blame and reproach, to be a subjective process. And so it is and necessarily must be. At the JCB prize dinner, a shortlisted young author came up to me and smiled and said: “Sir, you [i.e., the DSC jury] did not even put me in the longlist!” I smiled back and refrained from telling him that our longlist did not include even the winners of at least two major prize awarded only a few months ago, and about 10 other very worthy novelists of long-standing eminence — for the good reason that none of the jurors ever recommended them.

However, prizes are decided by not just one eccentric subjectivity, but three or five equally eccentric subjectivities in intense interaction and equations among the jurors or their group chemistry may also play a role here. Actually, this process in itself may be a fit subject for some future novel — which perhaps should not then expect to go on to win a prize! On the other hand, different prizes often have overlapping shortlists and sometimes even the same winner. Collective subjectivities may often verge on the objective.

The DSC jury this year was required to read 90 novels in just about 90 days, a whirlwind tour rather like going around the world in 80 days before there were aeroplanes. Quite early in the jury interaction, it emerged that the five of us had widely different preferences or “favourites,” and that’s when the fun began, for ultimately there could be only one winner. When announcing the DSC shortlist, I said in my formal statement: “The shortlist that we have arrived at comprises six novels — for the good reason that the five jurors, located in five different countries, could not agree on just five.” In the informal part of my speech, I repeated what I had said at the announcement of the longlist, that when the jury finally meets to decide the one winner, I fully expected blood on the floor. This got the director of the DSC prize seriously worried, and rumour is that throughout our 150-minute jury meeting in Nepal, he stood outside our boardroom with a hotel worker ready with a bucket and a mop.

My lips are still sealed and my tongue still tied about what precisely transpired behind those closed doors, though I was told that going by the constant bursts of laughter that were overheard in the corridor, the impression was generated that it was a party going on inside and not a serious meeting. I may reveal that a couple of weeks before, I had emailed my fellow jurors urging them to increase their hours of daily yoga and meditation and train their minds to arrive at a state (as prescribed in the Bhagavad Gita) where they would be equally happy or unhappy at any of the six shortlisted novels winning the prize.

I myself got only half-way there to becoming a sthitaprajna, a person with a completely level head and an imperturbable mind. For, to make a true confession, I went into the meeting with three novels in my most secret and private A list — or more accurately, one favourite novel flanked by two semi-favourites. And I suppose my wonderfully genial and collegial fellow jurors were probably in a similar boat. Each of us argued the merits and demerits of each of the novels over two hours, with the kind of engagement and dedication that suggested that the future of fiction depended on what we decided, or as if the big prize money was coming out of our own pockets. It was only in the last couple of minutes of the meeting, when the final vote was taken, that any of us found out who the winner was — which was of course just how the meeting had been planned to proceed.

Speaking the following day at the award ceremony of the prize, Ms Surina Narula, the founder-sponsor of the prize, said something entirely candid and winsome: that she had each year a favourite of her own, and that over the eight years of the prize, she had picked the winner four times. When I announced the winner for the ninth year a few minutes later, she told us her score had gone down to 4 out of 9!

In the two other prizes that I was involved in this year, the Sahitya Akademi Bal Puraskar turned out to be the simplest and the sweetest to decide. As soon as we met, it transpired that Urvashi Butalia and I had the same list of the top two books out of the 13 that we read, and it took just two minutes of conversation to make it one. In the Jnanpith award, it was a close vote at the end of two hours of sustained to and fro, as it often is, and thereafter we quickly arrived at a verdict that was officially “unanimous”.

As for being the chair of a jury, one may get a hugely disproportionate share of the limelight when the longlists and shortlists are announced and then, of course, the winner. But when it comes to the crunch, the chair has only one vote, and it can never be the casting vote if the number of jurors is three or five, as it nearly always is. Of the many different chairs that I have known (including myself!), some have led from the front (trying soft-footedly to keep one step ahead of the other jurors and hoping they wouldn’t notice), some from the back (going quietly and “graciously” with whatever consensus emerges), while a few end up being themselves led by the nose.

I heard at second-hand a lovely story about a past chair of the jury of one of the prizes we have been speaking of here. After he had announced the winner at a grand event, this chair was asked by someone, “So was that novel your favourite, too?” And he spluttered and said, “Don’t even speak to me about my favourite! It did not even make it to the longlist.” When I see this person next, I may well ask him, “So, what kind of a jury chair were you!” But, then, I suppose it takes all kinds.

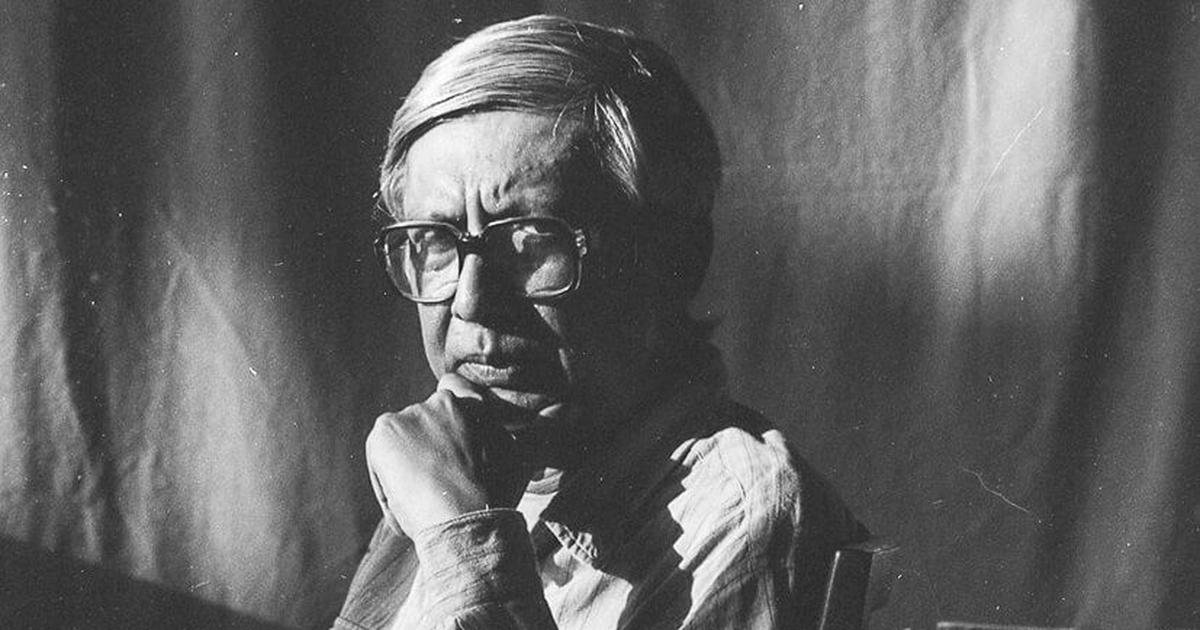

Dom Moraes. Photo: Speaking Tiger

I felt so riled at their sheer cussedness that as I, too, stood up, hardly able to believe what had happened, I could not resist a Parthian shot: “Mr Moraes, have the standards in English fallen so precipitously in just one year?” He flinched, his lips moved without producing a sound as he controlled himself, and then he marched off in a huff. The previous year, Dom Moraes himself had won the prize in English.

My own most discomfiting moment ever as a juror came many years ago, in 1995. It was at a meeting held in Bombay to decide the Sahitya Akademi award winner in English that year and my fellow jurors were Dom Moraes and Dilip Chitre. We had a shortlist of six books and as we began to go over them one by one, Dom would say: “But isn’t that book terrible!” Or “Simply awful!”And Dilip would chime in and say, “Rubbish!” I persisted and kept expounding the merits of each book, especially of the two or three I had really liked. But they were immovable. I suspected that as they both lived in Bombay they had already met and made up their minds.

I then said that not giving a prize at all would send out the wrong signal about the health of Indian writing in English of which they were both eminent practitioners. But a couple of hours passed and they still did not budge. The thought crossed my mind that they were perhaps playing a game and having me on, and just before we dispersed they would disclose a winner they favoured or even agree to one of my preferences. But, no, they stood up around 1 pm and said it was time for lunch. I felt so riled at their sheer cussedness that as I, too, stood up, hardly able to believe what had happened, I could not resist a Parthian shot: “Mr Moraes, have the standards in English fallen so precipitously in just one year?” He flinched, his lips moved without producing a sound as he controlled himself, and then he marched off in a huff. The previous year, Dom Moraes himself had won the prize in English.

That was a quarter of a century ago, and it’s too late now to ask either of them but maybe there is a confidant of theirs somewhere who knows what they were thinking. On return to Delhi, my dear old friend Keki Daruwalla asked me confidentially who had won and I could not refrain from telling him the sad tale. He was so outraged, for he is a staunch champion of all Indian writers in English good or indifferent, that he promptly narrated the episode in his weekly column under thin disguise.

I may say that after that singular experience in Bombay, it has pretty much been smooth and pleasant sailing. On different juries we have had differences of opinion and collegial give and take but I have never again known a juror act like a wall. And as time passes one acquires perhaps maturer judgment and a wider repertory of means of persuasion which may possibly help one even get round a wall. Anyhow, I can think of a couple of juries, if not more where, in all modesty, the outcome may well have been different had I not been there to argue a case and be (literally and metaphorically) counted. To drop a juicy broad hint, I was there for example when a namesake of the Buddha was in contention — and on more than one occasion!

But Why Prizes?

After my varied experiences, this for me is the million-dollar question. Why do we award literary prizes at all? What is their purpose and function? And if we must honour writers and offer them financial support, aren’t there better ways of doing it?

There would seem to be three ostensible reasons for awarding literary prizes: to support and encourage the whole endeavour of literature, to confer instant fame on one chosen writer, and to disburse a sum of money to a writer to enable him/her to carry on writing, aided by the spike in sales of the book which the award may bring. A subterraneous fourth reason may be to project the award-giving organisation as a wealthy body with an admirably enlightened philanthropic vision.

All this still does not explain why prizes must be staged as a winner-take-all contest — rather as in successive Mughal wars of succession to the throne, when there was indeed much blood on the floor and some severed heads besides. Why can’t we stop at a shortlist of five or three, and declare each to be a winner equally worthy of sharing the spoils? But that perhaps would never make the headlines and attract attention in our mortally competitive age. It may then even discourage the organisation putting up the money from continuing to invest in it.

Prize-giving events used to be quite “dignified” affairs until recently, and still are where the Sahitya Akademi and the Jnanpith are concerned, where only the winners are invited and given time to speak about their works and writing careers. But with the newer prizes, it is often a big media event to which all the five shortlisted writers are invited and all the five jurors, and sometimes assorted glitzy celebrities as well. One witnesses the same triumphant or bravely crest-fallen expressions on the faces of the so-called contestants at the announcement of the prize as at show-biz events, which are obviously the model for these events. “And the Oscar goes to…”

But are prizes the only true reward for a writer? What do they write for and what is the sort of recognition they yearn for as they put their souls and naked selves on the line? They long perhaps to connect with a reader or readers (the sahridaya as he is called in Sanskrit poetics, i.e., someone with a similar heart or sensibility) who would pick up the many nuances of meaning intended and planted by the author, and perhaps then some which even the author wasn’t consciously aware of putting in. Creative writing even in its most commercialized and monetized projections is at heart a mysterious business, for if it doesn’t plumb the depths of human consciousness and empathy, it is no more than what t

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated