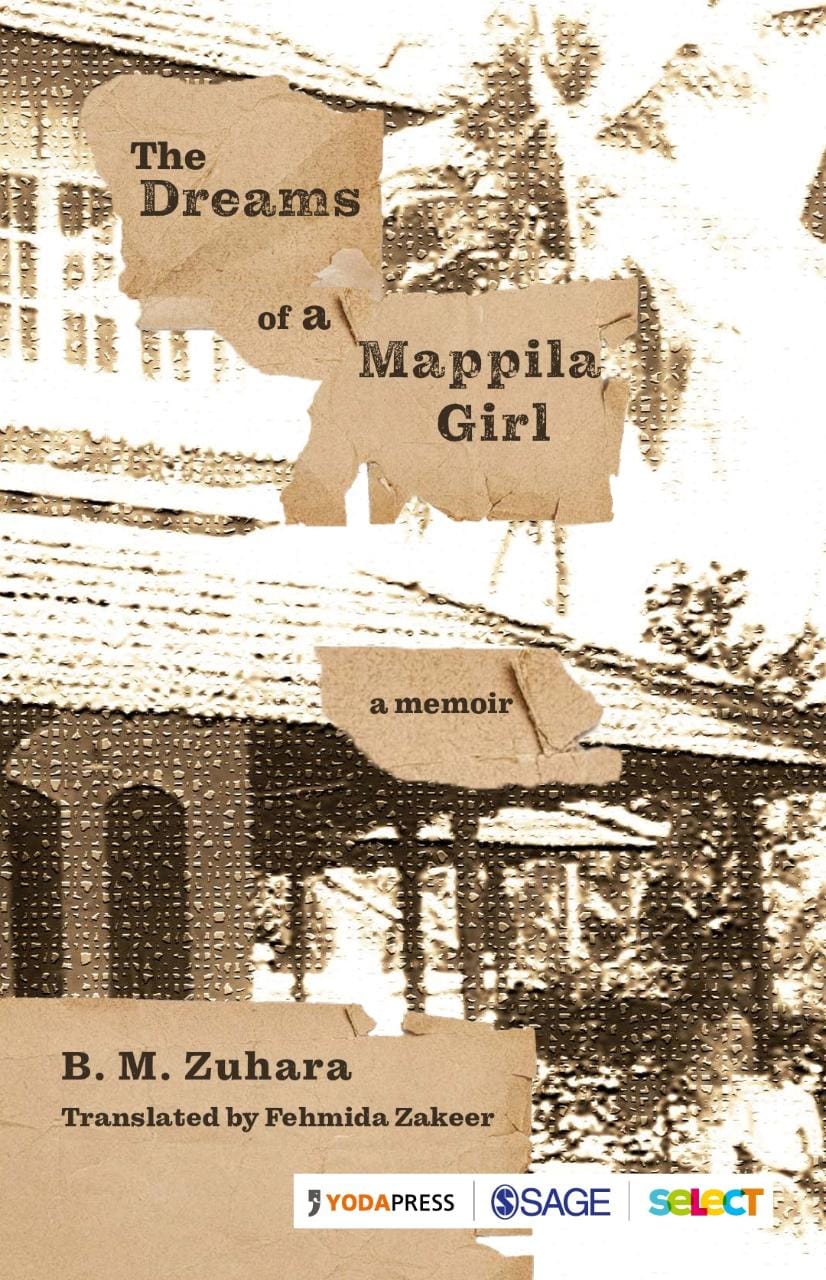

About the memoir: As a young Muslim girl growing up in the 1950s in a small South Indian village, B. M. Zuhara, the first Muslim woman writer from Kerala, had simple dreams—to go to the newly opened ‘talkies’ in town and watch a movie, play with her brothers in the rice fields, learn the ancient martial art of Kalari Payatu with them, stand on the bridge and listen to the songs sung by the farmhands as they worked. But she soon realised that even being the pampered, youngest child of her family would not help her in realising some of her dreams because of her gender. Set at the time when Independent India was embracing its new identity as a free nation, Dreams of a Mappila Girl provides a wide lens for the reader to view life in a semi-rural Kerala village. Zuhara recounts the social mores of the society she lived in and offers glimpses into the secluded lives of Muslim girls and women who, despite obstacles, made the best of their circumstances and contributed positively to their communities.

****

Even though I knew Ummama would be in the kitchen, I went to the verandah on the western side, where Uppa and my brothers practised their kalaripayatu in the yard under the supervision of Mammad Gurukal. Wearing loincloths, they practised noisily, shouting ‘Thadutho, Marinho, Edathu, Valathu, Othiram, Kadakam!’* Looking at them, ferocious longing reared inside me, combined with anguish at not being the right gender to learn this ancient martial art.

‘Why are you standing there looking lost?’ said Achu, rapping me on the head as he came inside.

All my sadness now dissolved into a waterfall of tears.

‘You know she’s just waiting for a chance to cry, and yet you provoke her,’ Uppa said reprovingly to Achu.

His words resounding in my ears, I made my way to the nalapad. I stood there deciding where I should go next, when I heard Ummama’s voice near the storeroom.

‘Kadeesa, come quickly, the azaan for the afternoon prayers will be called any minute now.’

I decided to go to the storeroom. Each afternoon, Ummama took out the provisions needed to make dinner and handed them to Kadeesumma. She was now hurrying to the storeroom, with Kunhamina following close behind her. Both of them carried winnowing baskets and pans and bamboo containers and jars of different sizes and shapes. The storeroom was filled with cupboards and wooden shelves at various heights. Ceramic jars and other containers lined the shelves. Ummama opened a small cupboard with four or five shelves. She took out jars containing spices —mustard, fenugreek, cumin and fennel seeds — and handed a little of each to Kadeesumma.

Unnoticed, I went over to the jar of tamarind kept in one corner of the room. I dipped my hand inside. A big tamarind tree grew just outside the kitchen. Ripe fruits were plucked, peeled and dried in the sun. Then they were rolled in salt, divided into small balls and stored in ceramic jars. Another ceramic jar contained mangoes preserved in brine all the year round. Mangoes were first boiled, then dried and then soaked in salted water. Whenever I visited the storeroom, I could choose to take the tamarind, or the mangoes in brine, or sugar crystals. I left the room only after helping myself to at least one of these tidbits.

In the monsoons, fishermen did not land their boats on the Kodikkal beach, and as a result the supply of fish was erratic. So in the summer, therandi, or sting rays, were dried and salted for use during the rainy months. On the western side of the house, golden cucumbers were left out to dry in cocoons woven from dried coconut leaves. Fried therandi, coconut chutney, yellow cucumber in red gravy — these were the special foods made over the rainy season.

During the monsoon months, many people, especially those who depended on the sea for their livelihood, saw their earnings dwindle. In some households, stoves remained unlit through the day. Women and children came to our house in the afternoons asking for rice water. Ummama always made it a point to remind the women in the kitchen to cook extra food during this time. ‘We should not turn away the people who come asking for some gruel and uppu manga, Kadeesa.’

Now, using a wooden spoon, Kadeesumma ladled out coconut oil into a glass bottle. ‘The oil will run out soon, but the copra is not yet dry.’

‘You people need a whole bottle of oil just to apply on your hair. It’s not even one month since we extracted oil from our copras, and now you’re saying it’s almost over!’ Ummama exclaimed, annoyed.

Coconuts were broken and dried to make copra, which was then taken to Payyoli to have the oil extracted. Chathu’s shop near Tikkodi School had the apparatus for extracting oil, but it was a small unit and could grind only a limited number of coconuts. After school, I sometimes stood there and watched the unit being operated by Chathu and his bull. They circled around the mortar, their movement turning the pestle that ground the coconut to extract its oil. ‘Hey, why are you standing there like a statue, come quickly,’ Achu would call out, and I would follow him reluctantly.

‘Moidyaka said that the coconut pieces have to be kept in the sun for two more days. Why don’t we make some oil at home?’ asked Kunhamina, who was holding the muram for the rice.

‘Yes, and that way you will get to eat the residue.’ Ummama dipped a wooden spoon in the jar to measure the level of the oil. ‘Rabbe, the level is so low, why did you not tell me earlier?’

‘I told you the night before last. You must have forgotten.’

‘Take twenty-five coconuts and grate them tomorrow. We’ll make some oil with that. Tell Moideen tomorrow morning that he has to take the copra for extracting oil the day after tomorrow. Is that clear?’

‘Yes,’ replied Kadeesumma.

‘Kadeesumma, please let me have some of the residue mixed with jaggery,’ I said, giving her a nudge.

The coconut milk extracted from grated coconut was heated on a slow fire, and stirred continuously till the oil separated. As the milk thickened and separated, a heavenly aroma rose and spread through the house. On cooling, the oil floated on top and the residue sank to the bottom. The light brown residue was delicious mixed with jaggery. Kunhamina would keep some aside stealthily, but Ummambiumma would catch her and take it from her.

‘If you steal, you will be cast into the lowest level of hell. I always give everyone their share. Then why do you want to steal in this way?’ Umma would lecture.

‘By God, by the Prophet, I am taking it only for Soora. It’s not for me at all …’ Kunhamina would say, wiping her eyes, and her distress made my own eyes tear up.

I stood there in the storeroom immersed in the memory of the aroma and taste of the coconut residue.

Noticing my presence now, Ummama asked, ‘When did you come in? Your mother will blame me when you start crying at night. You will get a stomach ache if you eat tamarind and salty mangoes.’

I quickly put the rest of the tamarind in my mouth and displayed my empty hands. ‘Look at my hands. I don’t have anything. I only took a pinch of tamarind. Don’t tell Umma, she’s always looking for a reason to scold me.’

Everyone started laughing.

* Chants defining movements in kalaripayatu.

Excerpted from The Dreams of a Mappila Girl: A Memoir by B. M. Zuhara; translated by Fehmida Zakeer. Jointly published by SAGE Publications and Yoda Press under the Yoda-SAGE Select imprint (pp. 228 , Rs. 550)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated