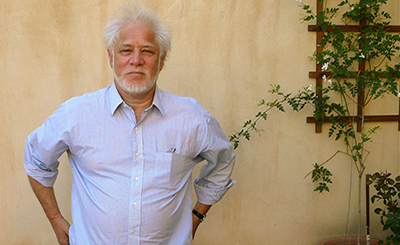

Maitreyee B Chowdhury. Photo courtesy of the author

Poet’s Note: ‘Kabir taught me simplicity of form and thought’

My journey as a poet started while in high school with a reading of Kabir and his poetry. While the love of Kabir never left me, it taught me valuable lessons in simplicity of form and thought, while also leading to a larger journey towards Sufi poetry. As a student of literature, I’ve studied a lot of British and American poetry and its trends, but it was only when I started serious writing myself some fifteen years ago that I started turning more towards poetry from this part of the world and in as many languages as possible. In many ways that was a turning point, for this was poetry about my kind of life, of a similar language scape.

More and more of the poetry we read and write is often devoid of stringent structures thankfully. How the poet wants to structure their poem should be a choice they have — and so it is with my poems too. Being a poetry editor, I’m privileged to read a wide variety of poetry and it has made me delve deeper into translations from South East Asian languages and publish more of that. My own writing has turned inward and I find myself immersed in subjects that are part of my history. Migration, partition, capturing the emotion of sound and the journey of evolution through food are aspects that intrigue me now.

The pandemic has given us different dimensions as poets, I think. Like the blind adjusting to a new smell. It made me fulfil a long dream of writing poems while on the road. I walked incessantly and wrote about aspects of my city in ways I haven’t before.

39, Broad Street

39, Broad Street is a pensioner’s home —

everything is old in here,

only the sex on random afternoons is new.

A daughter, and a son,

their photographs at odd angles hang in each bedroom.

I shift the daughter’s altered curvature

into a perceptible straight —

habit is an unnecessary square,

everything must be vertical within a frame.

Oval Bengali eyes and freshly plucked eyebrows

in a leafy patterned dress

stare back at me,

from a probable class ten —

I note to myself.

On another wall, she’s in college,

the hair longer, the face slimmer —

the saree tucked in polka dots.

I wonder whether a man had appeared by then,

the oval eyes look disapproving

this time.

My untied hair looks callous on an old bed,

polluted once by love,

habit and marriage.

‘Ma is in the hospital’, I’m told —

‘Nothing major, a torn ligament, and an odd chest pain.

Common at this age.’

I nod and look around,

curious and still.

It is an October Pujo,

the dhakis are here on time.

Chaos and afternoon spill overs too —

Naresh the durwan hovers in quiet corners,

his shadows have grown longer

since the year before last,

and the year before that

when I had walked here, in quiet.

He still doesn’t look up though

and the silence is a half-hearted television blur

on another’s afternoon wall.

My red saree lies in a heap by the bed,

the year before, it was rust.

She won’t hear us;

two walls separate a hospital bed

from unused wedding spoils —

old age and more old age here

a garlanded husband in another wall,

looks peaceful meanwhile.

Such a blessing I think,

walls with conscience

are an embarrassment

for those without direction.

I dress in a hurry,

moan in a hurry,

love in a hurry.

Another’s house, another’s memory,

another’s marriage

are unaccustomed ghosts.

In trying to find love here,

my eyes don’t flutter,

rest or sleep —

convenience is everything.

How To Grow a Rhododendron

First, right the spelling.

The spell check comes up with bizarre options

that you don’t recognize from the colours of the flower.

The rhododendron is often red,

also, pink and lilac you’re told.

A singer I knew once tried to eat them,

and grow into that colour in his songs.

You blow on the back of the flower,

the delicate pink ready to melt into your mouth —

But you taste with the heart, always the heart

nothing gets forgotten in the heart

and memory here is forever.

So when you leave the hills of rhododendron,

find some seeds and water them with care —

wait now,

by growing old and turning pink-in rhododendron language.

And if you don’t see a flower still,

understand that like you, its heart is lost.

The language of dreams long forgotten,

and colours complicated forever.

Like you,

the flower remembers the smell of the mountains.

It dwindles, in your dreamless, freedom-less

little balcony in Koramangala.

The scents are not the same here,

the grass isn’t as green,

the gardener must have forgotten to water the seed

you think —

but what would you do of memory,

that kiss of the clouds the flower never forgot,

the pace of slow, you somehow forgot.

You realise then,

that cross pollination and hurry are diseases,

it screams of the lack of science —

and psychedelic chlorophyll nights,

are where plants are happy and doped.

The way you touch the flower,

kiss the plant and eat the red — is everything!

Don’t let that memory go,

turn it into your reclamation song instead.

Go grow your rhododendron in the spring,

in some village buried beyond.

But spell check for the spelling first,

get that right, and then sow your seeds

in rhododendron colours of the hills.

Pice Hotel

There’s the desire to kiss you.

In the bylanes of Dharmatala,

find a seedy hotel with green shoddy curtains

and cheap tin spoons.

Where men wear yesterday’s satin ties,

and kiss women in frilled pink petticoats.

Where tea is a mixture of yesterday’s thought and today’s brew —

There, where

the chairs are a plastic Red,

bent somehow in anticipation

of transient love and lonely Sundays —

Where lonely men eat with themselves,

while turmeric stained nails,

talk to yesterdays’ fish.

There —

in a God lined blue wall

your smell became mine —

stale from whitewashed, distempered love

mixed in the incense of a discarded ten Rupee note,

we climbed walls

and stayed Red.

There, where the Pice hotel still stands

forgetting is easy and remembrance long.

* First published in The Sunflower Collective on 12/29/15. Pice hotels are cheap Calcutta eateries in dingy lanes, with garish walls and eclectic ambiance.

Between Sleep and Blindness: Flailing Light

Caught between sleep and alarmed wake,

you walk back home.

Waylaid by grass,

on a whim you stop, forget, lie down —

curious to see that growth again,

tremendous.

From seed comes ingenuity-you think

like a blind man smelling his hands in light.

You observe the grass,

this meticulous aversion to homogeneity

in each blade.

You think of time, then.

Time was when, the Jolpai would fall on rusted tinned roofs,

in a slow village by the Dihing —

music is a blank verse here,

like an engine falling into a lake

and memory, everything and beyond.

All night long you count the numbers,

Jolpai greens — now salt, now peppery, now sweet.

Day light is weary and too soon,

cold as sleet — you rise.

Buried in your brains is the bare music of silence,

of growth falling down.

You finally realize the crack,

from where the night smelt of citrus,

and you let the light in.

Tremendous flailing light.

*Jolpai- The Indian olive

* First published in the Mud Proposal

The essay and the poems are part of our Poetry Special Issue (January 2021), curated by Shireen Quadri and Nawaid Anjum. © The Punch Magazine. No part of this essay or the new poems exclusively featured here should be reproduced anywhere without the prior permission of The Punch Magazine.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated