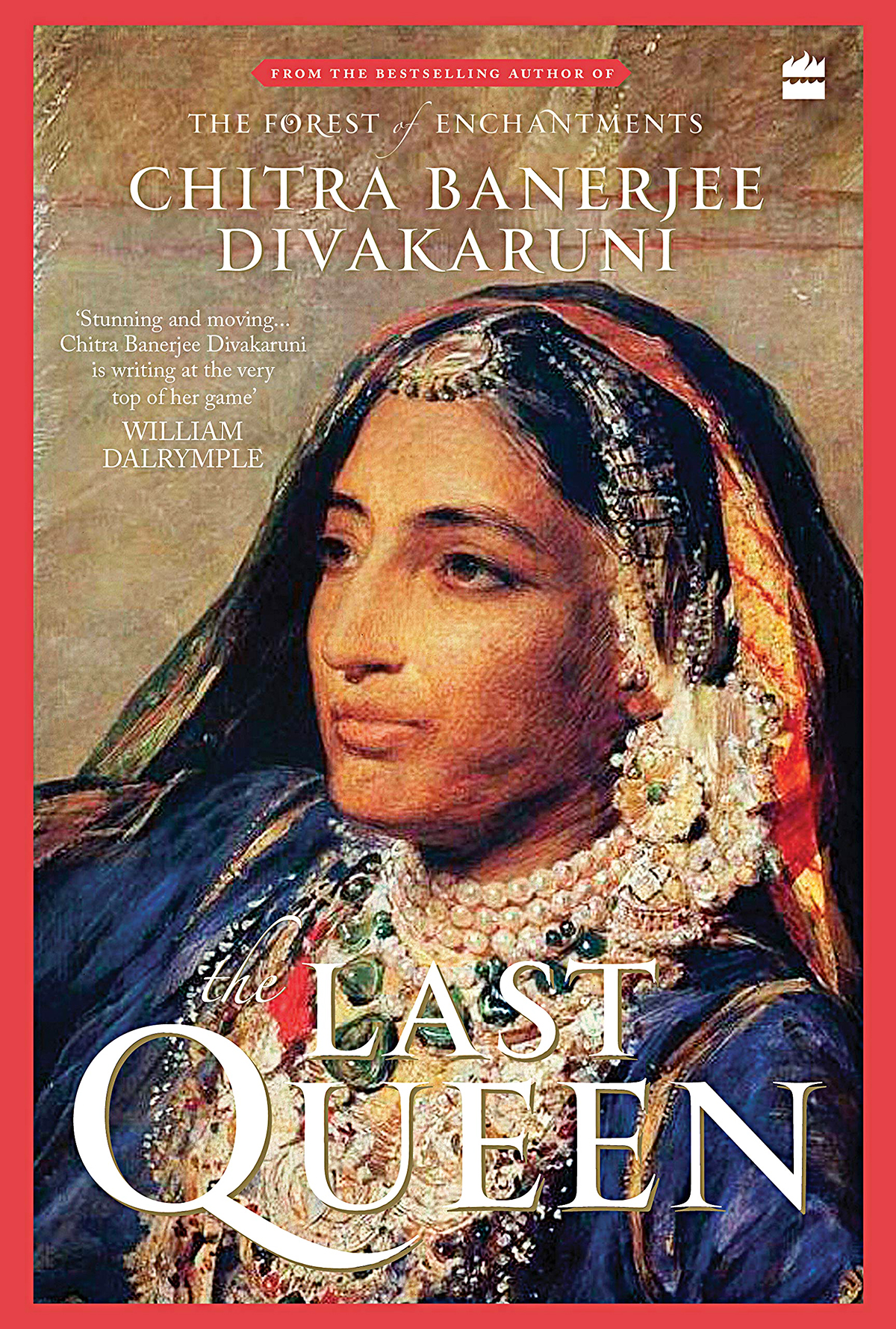

Rani Jindan Kaur. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The novel brings to life the youngest queen of the greatest Sikh ruler, Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Daughter of a kennel keeper, Jindan Kaur became a member of the royalty, gave birth to the King’s heir, found love again after she was widowed at 21, and valiantly fought the British

Not many people know the heroic, awe-inspiring story of Rani Jindan Kaur, the youngest queen of the greatest Sikh ruler, Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Bestselling author Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni's latest book The Last Queen (HarperCollins India, 2021) is the subject of Jindan’s captivating story. The novel, which has already been optioned for film rights, is told in Jindan’s first person, and is divided into four sections that chronicle the most important phases of her life in detail: Girl (1826–1834), Bride (1835–1839) , Queen (1840–1849) and Rebel (1860–1863).

Jindan believes that she wants something badly enough, she can make it happen. “How else could she, a girl from a no-name family on the outskirts of a small town, end up in Lahore, city of emperors? How else could she possess a haveli in the heart of this fortress textured by centuries of history? How else could she, the daughter of a dog-trainer, become the Sarkar’s favorite queen? How else could she give him what many of his wives, though they were married to him in his prime, failed to produce: a son to delight his old age?”

Jindan’s childhood is spent in a village hut on the muddy edge of Gujranwala. As a feisty nine-year-old, Jindan joins her older brother, Jawahar, in his exploits of stealing fruit from nearby orchards and fights with boys. Her mother allows her to study, unlike other girls, and she is a great student. However, after an abrupt end of her education, her father, Manna Singh Aulakh, who works and lives in the Badshahi Qila, takes Jindan and her brother to Lahore, “a magical city filled with riches”.

With its vivid imagery and detailed descriptions, the book recreates a timeless era gone by, making it truly come alive in the reader's mind. From her father, young Jindan has grown up hearing several stories of the king and the palace: “The fair-skinned dancing girls from the hills of Kashmir who perform all night for him in the Red Pavillion; his ghorcharhas, a cavalry made up of the bravest young men in all of Punjab, unbeaten in battle; kennels full of the fiercest hunting dogs; enclosures for the royal elephants; and stable upon stable of pedigreed horses, culled from several countries.” She longs to experience all these magical things herself.

At the palace, she encounters the charismatic Maharaja Ranjit Singh while her father is tending to his horses. Ranjit Singh, known popularly as the Lion of Punjab, takes her riding on his special horse, Laila, and to a banquet afterwards. He tells her fascinating stories of war and other adventures, and finds Jindan not just beautiful but also brave, curious and intelligent. Even though all his other queens are of royal birth, he finds that the spirited Jindan understands him and loves Punjab as fiercely as he does. In no time, they are in love and get married. Soon, Jindan becomes the king’s dearest queen and is showered with gifts. When her son, Dalip, is born, the king gifts the queen a haveli named after her.

The Last Queen, By Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, HarperCollins India, pp. 372, Rs 599

After the king’s death, however, Lahore has several kings and sees many battles. Jindan and her son are exiled in a fortress in Jammu. When the king's heirs are all killed and murdered one by one, fate pushes Dalip close to the throne. When young Dalip is finally summoned to become the king, Jindan is made the queen regent until he reaches adulthood. In her new role, she fights hard against the British as well as her own treacherous courtiers. Along the way, the prose is sprinkled with much politics, plots, spying games, tricks and endless battles for power that are a part of royal life.

In her signature style, Divakaruni manages to breathe life into the character of this enigmatic historical figure, making her seem more real and human than any textbook ever has. Widowed at the age of twenty-one, a lonely Jindan also gives into her desires and miraculously finds love again in Lal Singh, a nobleman in the Lahore court. Wise beyond her years, she finds reasons for her actions: “Many of the nobles have several wives — and mistresses, too. Their liaisons are accepted. Am I sinner, just because I’m a woman?”

Later, Jindan is separated from both her son and loyal maid, Mangla, when she is imprisoned in Sheikapura Zila and then banished to Chunur Fort in Benaras. When the British snatch away the kingdom of Punjab, she manages to escape to Patna and then undertakes a dangerous journey all by herself to Kathmandu, where she seeks refuge. The British, meanwhile, spread many lies about her and even name her the 'Messalina of the Punjab.’ “In her way, wasn’t she braver than Ranjit Singh?” Didn’t she fight greater obstacles?” Jindan’s courageous life proves that she was no less than a lioness herself.

After being estranged from her son for a period of fourteen years, she is reunited with him once again in Calcutta, and they live the last few years of her life together in London. Known as the “Black Prince”, Dalip had neither the strength of character nor the stubborn focus that his father possessed. Filled with fantastical plans and extravagant ideas, he was fickle and confused between his loyalty to India and the British. Before she died, Jindan reminded Dalip of his heritage, asking him to conduct her last rites in India and place her ashes next to her husband’s. Unfortunately, it took the British a whole year to give Dalip permission to bring her body back to India from England.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

THUMB.jpg)