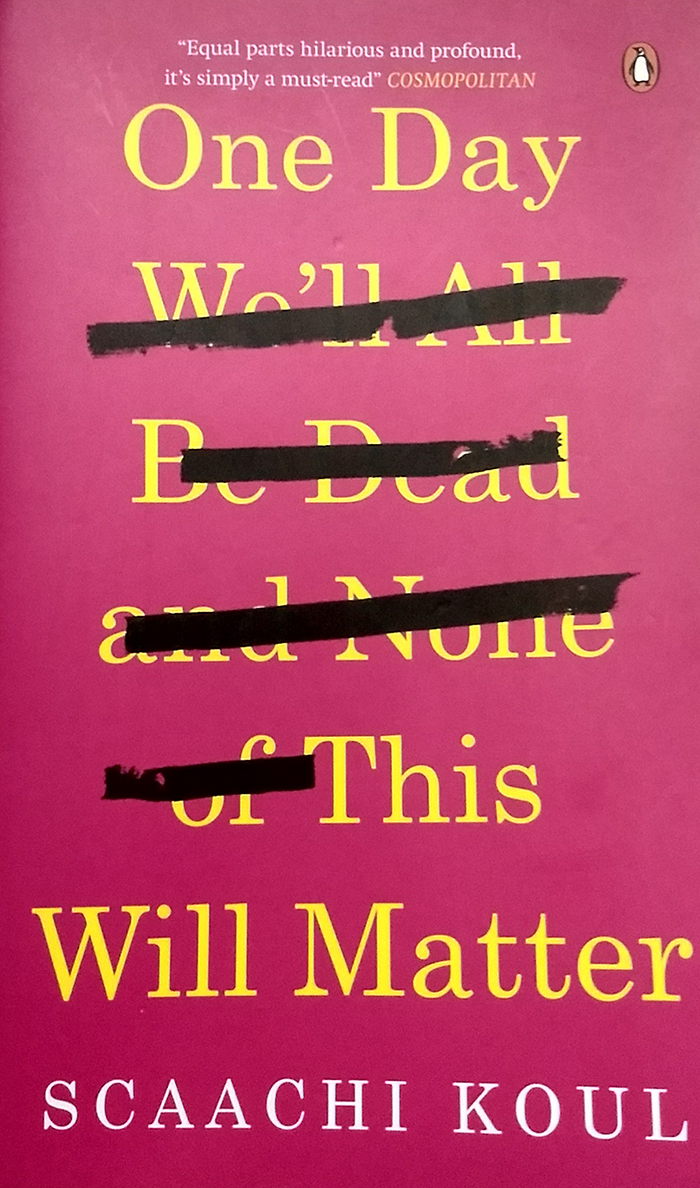

Scaachi Koul. Photo courtesy of Penguin Random House

In One Day We’LL All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter, the crux of Scaachi Koul’s essays deals with growing up and living in Canada, a country known to be an ideal refuge for immigrants barred by a belligerent neighbouring country

On February 18, 2016, Scaachi Koul, an editor and writer at BuzzFeed Canada, send out the following tweet asking her Twitter followers to submit freelance pitches:

Would you like to write longform for @BuzzFeedCanada? WELL YOU CAN. We want pitches for your Canada-centric essays & reporting.

This was followed by another tweet:

@BuzzFeedCanada would particularly like to hear from you if you are not white and not male.

This was followed by another statement:

IF YOU’RE A WHITE MAN UPSET THAT WE ARE LOOKING MOSTLY FOR NON-WHITE NON-MEN … I DON’T CARE ABOUT YOU … GO WRITE FOR MACLEAN’S.

Quite expectantly, Koul’s Twitter feed was inundated with tweets that started with generic trolls and later, became threats filled with racist and sexual vitriol that included rape, death, and abuse.

Incidents of threatening women with physical harm are not new on Twitter or on any social media platform for that matter. Neither was Scaachi Koul new to trolls on her Twitter feed. She is known for her blunt style and her support for non-white non-heterosexual voices in the media. This often rubs certain sections of people the wrong way. So she knows very well how to handle the hatred spewed against her, by deflecting the toxicity with humour, “even if the way to doing it means making another dick joke”, as Koul says. However, this time, Koul decided not to participate in the game. This time, the volume of threat was too overwhelming. This time, it hit home too close. Because this time it was, as she says, “…a targeted attempt to make me question my physical and emotional safety.” Koul deactivated her Twitter account.

Only to get back two weeks later, with a series of GIFs of The Undertaker resurrecting himself after a fight. Quite symbolic. In an essay titled Mute in her debut book One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter, Koul writes how reactivating her Twitter account was not exactly an act of bravery, but an obstinate resolve to not secede a space she called her own. With brutal honesty, Koul writes about her indignation on being forced out her playing field:

“I like being in spaces where I am not welcome because you do not deserve to feel comfortable just because you’re racist or sexist or small-minded. Something about ceding this territory, this part of the digital world that I felt ownership over, felt so deeply unfair. It’s my house, why should I leave?

I hated being offline, because I wasn’t a martyr and I wasn’t brave and I wasn’t weak. I just didn’t like the game, the rules of which I helped write.”

With its pink cover and pragmatic yet cheery title, Koul’s collection of personal essays may seem like a fluff piece in a magazine. However, this thin volume is anything but fluff. Covering a range of topics from abuse against women on social media, racism, shadeism, immigrant experience, body image, female body hair, family, anxiety about death of loved ones, over-the-top Indian weddings, alcoholism, and rape culture, Koul writes about subjects close to her and stories that are interesting and relatable enough to share with readers, more specifically brown girls and women. In her interview with The Wire, Koul explains her intention behind writing One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter:

“I wrote the book for brown girls first, and everyone else second. I don’t remember reading a ton of books by brown women to begin with, never mind non-fiction books by brown women, so I did want to fill that gap at least […] I wrote about things that felt honest and important to me and everything that came after it speaks to either how starved that market is, or how the essays are funny and thoughtful (I hope)…”

It’s not that there is a dearth of books and writing by women about women and their bodies. These are very personal subjects, but there are hardly any writing that had the potential for a universal appeal; you will rarely find a writer writing about modern feminism that speaks to all women, irrespective of sexuality or colour, except perhaps Roxanne Gay. Of course, there are the likes of Lena Dunham and Caitlyn Moran. But their writings are more white, or what has been called “white feminism”. In the midst of this pre-existing body of works, Koul’s book seems like something new and refreshing.

Perhaps she is catering to a niche group of readers, yet it is quite relieving to read about Koul’s everyday struggle with body hair that grows and sprouts in places they are not expected. Especially when it is accompanied by a hilarious anecdote about how her first waxer almost had a stroke attack while doing a Brazilian wax. Or when she writes about each shopping trip ending in a series of frustrations because clothes are manufactured assuming all women are created equal, that is, in petite sizes. Koul’s exuberance on finding a single piece of garment that would change how she sees herself or how the world perceives her is very relatable.

Writing autobiographical essays can be tricky. It is easy for the writer to fall into a trap of self-indulgence, to lose the reader the moment a feeling of disconnected creeps up. But this does not happen with Koul’s book. Her subjects may seem commonplace, but the perspective is new. She examines her life as a millennial woman, as someone who belongs to a minority, a woman who is firebrand on social media and wants the approval of her parents to be with the man she loves, a man who is white and a decade older than her.

Contrary to what might be expected from Koul’s book, she doesn’t dwell much on the immigrant experience or the sense of unbelonging. The crux of her essays deals with growing up and living in Canada, a country known to be an ideal refuge for immigrants barred by a belligerent neighbouring country. According to Koul, racism has been an inherent part of Canadian culture despite its recent progressive political policies towards minorities and immigrants. In the essay “Fair and Lovely” that deals with shadeism and racism, Koul writes about how Canadians (especially the white majority) barely acknowledge the existence of racism in the country: “…our inability to talk about race and its complexities actually means our racism is arguably more insidious.” Koul belongs to a Kashmiri ancestry that makes her light-skinned and not quintessentially brown. This makes her almost acceptable in the grand narrative of racial discrimination:

“…I am passable. I’m not white, no, but I’m close enough that I could be, and just far enough that you know I’m not. I can check off a diversity box for you and I don’t make you nervous—at least not on the surface.”

Being somewhere in the middle of the skin-tone scale gives her certain benefits as well as some unpleasant experiences (airport security giving her an extra pat down or magazines asking her to write only about Indian issues or a man she dated telling her she is too pretty for a brown girl). On the other hand, she is given a privileged status because of her light skin on her visits to India. Nowhere is this superiority of fair skin more prominent than in Indian weddings and marriages with matrimonial advertisements “lauding the ‘wheatish’ complexion […] right next to income and height”, and where as an unspoken rule brides with fair skin are considered as “prize”. Koul notes cheekily the country’s obsession with everything ‘fair’ to the extent that there is a “skin-whitening cream marketed for your unacceptably brown labia.” She observes how the colour of skin is so deeply intertwined with class in the Indian collective consciousness, as opposed to being a label for racial slurs back home in Canada.

Interspersed between her sparkling essays, there are little email conversations between Koul and her father with whom she shares a warm relationship and a common hatred for toaster ovens and a shared fear and anxiety about death. With a prose that is at once sprightly and poignant, Koul’s essays give a fresh perspective on the life of a woman (or a woman of colour) in contemporary times.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated