Kosi River valley near Almora, Uttarakhand. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Uttarakhand has been host for centuries to ascetics and mendicants who sought peace as they trekked the Kailash-Manasarovar and Kedarnath-Badrinath pilgrim routes

The word ‘pahad’ in Hindi has connotations beyond the literal English translation of ‘hill’. It encompasses not only the geography of the region but that elusive concept of the mountains as a spiritual entity inhabiting space conceived by an elevated state of mind. Indian scriptures suggest that ‘sanyas’, the fourth and the last leg of a man’s life, should be spent in realising spiritual goals through pilgrimage or ‘deshatan’. It is commonly held that a culture of pilgrimage, ‘tirthasthan’, is a continuation of the tradition of ‘deshatan’. Certainly, this land has been home to religious tourism through the ages. The geography of Uttarakhand is littered with Hindu mythological references, from the city of Haridwar or Mayawati to Badri Kedar, Yamunotri, Gangotri, Jageshwar and Baijnath, to name a few.

The early explorers of these mountains were Hindu pilgrims, who developed the pilgrim routes to the Hindu shrines in the Garhwal Himalayas. These mountains were impregnated with spiritual aura, and intellectuals as well as seekers of spiritual truth were attracted to them. Though the all-pervasive Hindu aura is difficult to escape in neighbouring Kumaon as well, the temples here are less denotative of High Religion than the Garhwal hills, where the famed Badri-Kedar temples lie. Aside from the Holy Trinity of Hindu gods (Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh) who have undertaken primordial feats here, there are the littler goblins, ghosts, demons and fairies, conjured by the less-sophisticated minds of agriculturists and herders, that collectively form a greater pantheon of deities.

Apart from rulers, administrators, missionaries, artists, plunderers and waves of migrants from the plains, Uttarakhand has been host for centuries to ascetics and mendicants who sought peace as they trekked the Kailash-Manasarovar and Kedarnath-Badrinath pilgrim routes. It is said that the Indian spiritual texts — the smritis of Hindu sages Vyas, Vashishta and Bharadwaj — were revealed here, while the trade routes to Tibet stimulated both cultural and spiritual interflows. As testimony to the popularity of these routes, the Laawaris Fund was constituted in colonial times with the unclaimed cash and belongings of pilgrims who had died on the Pilgrim Road. Before the Hindu saint Shankaracharya’s intervention in the eighth century, not only did Buddhism flourish here but had also travelled to Tibet via the trade routes.

During the 18th century, these hills began to be peopled by those who came to appreciate the benefits of a salubrious climate, and the culture of hill stations began to grow — Almora, Bhowali, Ranikhet, Lansdowne, Mussoorie, Mukteshwar and others. The Anglican Bishop, Reginald Heber, has described his journey to these parts in Narrative of a Journey through the Upper Provinces of India 1824–1825. He detoured through Kumaon on his way from Calcutta and travelled in a dandee.

The concept of summer retreats was not entirely new. Binsar had been a favourite summer retreat for the Kumaoni ruler Kalyan Chand (r. 1730–1747). He built a temple here dedicated to Shiva under the name of Bineswar, which, over the years, became shortened to Binsar in local parlance. The god is said to protect the dwellers on this hill from theft. There is a picturesquely located Kumaon Mandal Rest House upon the neck of the mountain. The road to Binsar gives one an opportunity to pass through a thick forest of rhododendron and oak. One can have a panoramic view of the Himalayan range from any vantage point early in the mornings. Binsar is located at an altitude of over 2,200 m, and its temperature is generally ten degrees lower than that of Almora. As a result of these factors and the breathtaking views it offers, the British, too, succumbed to its charms, as had the earlier Chand rajas who made it their summer capital. An interesting old building that still stands is built in the style of a magnificent English country house, and was owned by a rich Indian, a certain Mr Harbola, who, it is said, later sold it to Henry Ramsay. Surrounded by a magnificent forest of deodars and commanding a fine view of the valley, it is said to have been furnished with portraits of Victorian nobility and its walls decorated with heads of stags and thorals, mountain leopards and black bucks. Another well-known heritage property here once owned by Ramsay is Khali Estate.

After the British ‘discovered’ Kumaon, the wholesome climate of the region attracted artists and scholars from all over Europe, many of whom settled here and assimilated with the local ethos. Quakers such as Hugh MacLean explored the hills, anxious to demonstrate their faith to the skilled communities of farmers that lived off the land. There were seekers of another kind too, who were to make Almora their halfway home. Almora’s culture is steeped in Hindu spiritual tradition. ‘In 1942 I remember seeing a Danish sadhu dressed in saffron robes and pugri wandering around the hillside ... known as Brother Alfred since’, recounts Carol Pickering, once an English resident here.

In the early 20th century, Swami Vivekananda spent some time in Kumaon; it is said he experienced an epiphany at Brighton’s corner in Almora, close to where the Ramakrishna Mission now stands. The campaign to promote greater awareness of Hindu tenets was carried out by him in 1897. It started in Colombo and terminated here at Almora. Vivekananda’s disciples established an enchanting retreat beyond Lohaghat, known as the Mayawati Ashram. Mahatma Gandhi, enthralled by Kumaon’s scenic beauty, established another ashram at Kausani, the Anashakti Ashram. The Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore lived for long spells at The Deodars Hotel on Almora’s main bazaar road. It is said he composed many poems here, including ‘Sajuti’, ‘Nav Jatak’, and ‘Akash Pradeep’, and his book on science Visva-Parichay.

Through the early 19th century till Independence, the Almora hills continued to grow a reputation for seekers, poets and writers. Questioning came later with movements in theatre, belief in the supernatural, and a new cultural stratum was cast upon an ancient fort, the Navadurga and Asht Bhairav temples of Almora. Besides the acclaimed dancer Uday Shankar, who set up a dance company at Almora, many writers, artists and poets found inspiration for their creativity amid the beautiful surroundings of Kumaon.

Enchanted by both Hindu philosophy and the international reputation of Nobel laureate Tagore, a wave of Western artists and writers, and seekers of truth, settled around another pocket of Almora called Kalimat, thereby giving Almora its Bohemian stamp. The more-established British gentry of Nainital called them the ‘Almora cranks’ and the bend in the hill came to be known as ‘Crank’s Ridge’. Author M.S. Randhawa mentions in his book, The Kumaon Himalayas, a Dutch recluse who lived at Avonlea in Almora where she sniffed at her sugar, convinced that the licentious bania shopkeeper cast spells and cheated her. Her neighbours were the well-known American artist-couple Earl and Achsah Brewster, clad usually in white, who came from far-off Oberlin, Ohio, USA. Brewster’s paintings of the Kumaon Himalayas are well-known treasures for the few who possess his work.

It is said the ruler or Nawab of Rampur used the services of a German painter who lived here to paint over the nudes (in his collection of paintings) in night dresses out of modesty. These Westerners made the hills their physical and spiritual home. Other foreign artists living here, who would go on to become well known, were the Brunners, who lived at a house called Saint Cloud. Elizabeth Brunner gained fame as a mystic painter. Elizabeth had sailed from England with her mother, Sass. Elizabeth and Sass Brunner later rented a cottage in Nainital called Snow View. Many other Europeans came out from Europe during the turbulent times between the two World Wars. The atmosphere in Almora was different from the starchy British establishment that developed at Nainital, or the culture of cantonment towns such as Ranikhet. Later, in the 1960s, Almora became the setting of the romantic Chhayavaad movement of poets Sumitranandan Pant and Mahadevi Verma who sought the mystic experience.

Today, the new migrant to the hills is very different. While it is the summer influx that brings tourists from all over India to the mountains, increasingly, it is non government organisations (NGOs) and development specialists who make them their home round the year.

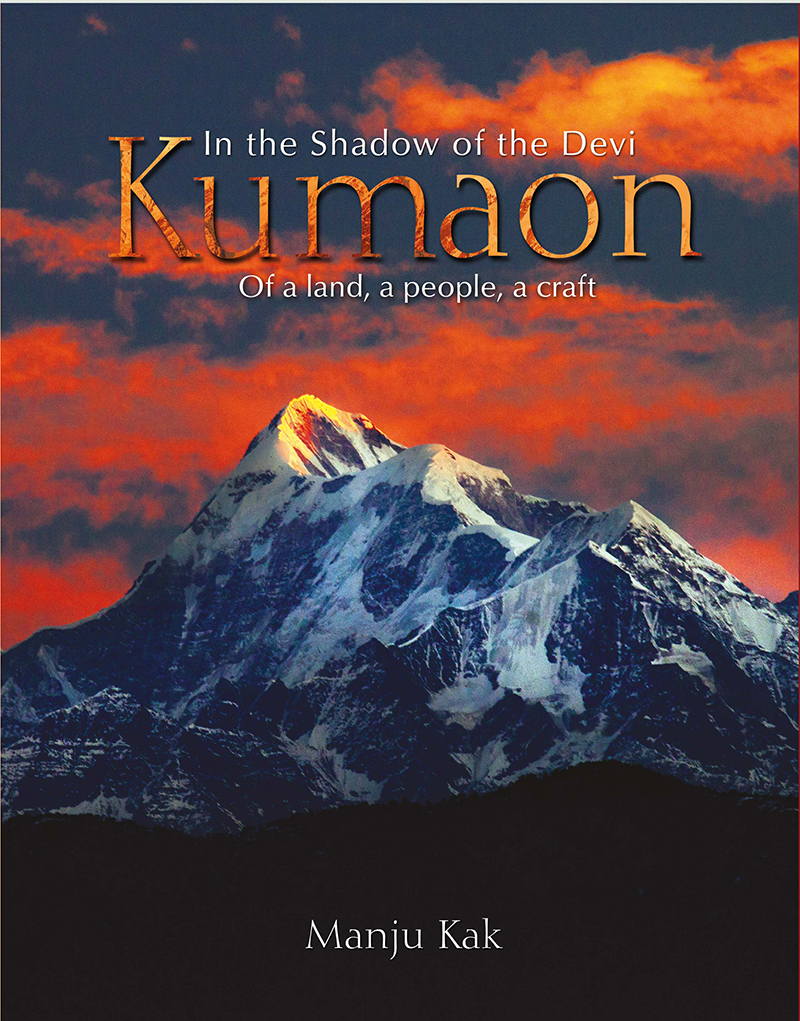

Excerpted from In The Shadow Of The Devi Kumaon: Of A Land, A People, A Craft by Manju Kak, with permission from Niyogi Books

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated