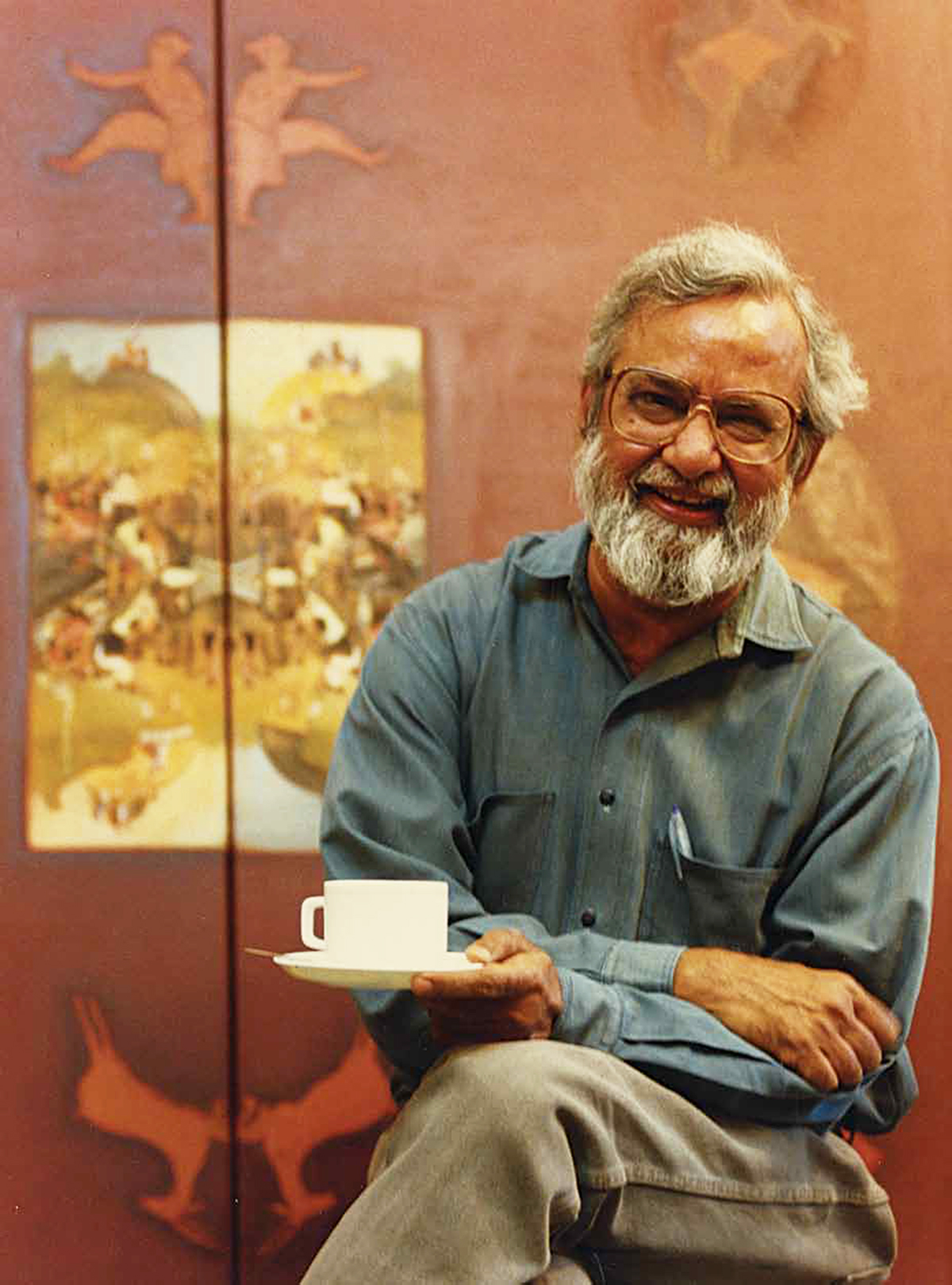

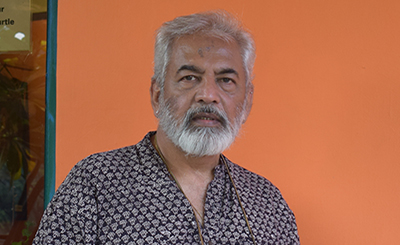

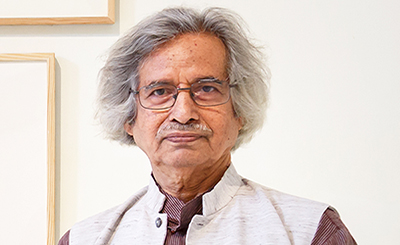

Gulammohammed Sheikh in the Niharika residence studio, Baroda, 2001. Photo by B. Jayachandran), courtesy of Tulika Books

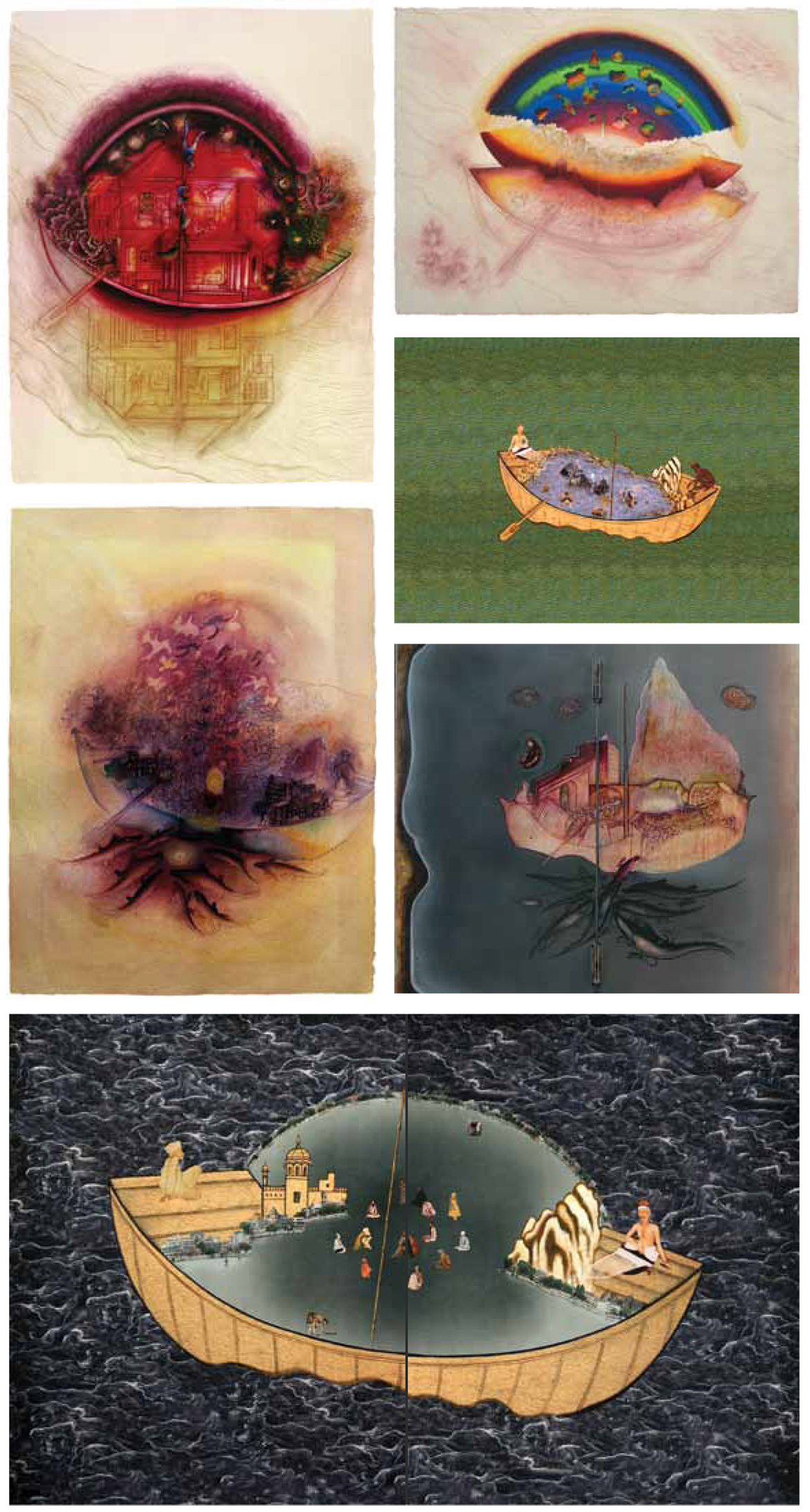

“A person is never easy to describe, especially in relation to his work. We use the tools of language to bring together a synthesis of a person, and the completeness of such an endeavour takes form in books,” writes Arun Vadehra, director, Vadehra Art Gallery, in his Foreword to At Home in the World: The Art and Life of Gulammohammed Sheikh, edited by Chaitanya Sambrani. Published by Tulika Books, in association with VAG, the book takes a close and comprehensive look at the wide universe of Gulammohammed Shiekh’s eclectic and multifaceted art practice, refracted through details of his personal life. Sambrani, who studied art history at the Faculty of Fine Arts, MS University of Baroda, has known Sheikh for nearly three decades and he writes with the vantage point of the artist’s student, protégé and friend. In the first five chapters, he provides a biographical context to Sheikh’s artistic trajectory and assesses his works in the light of art history.

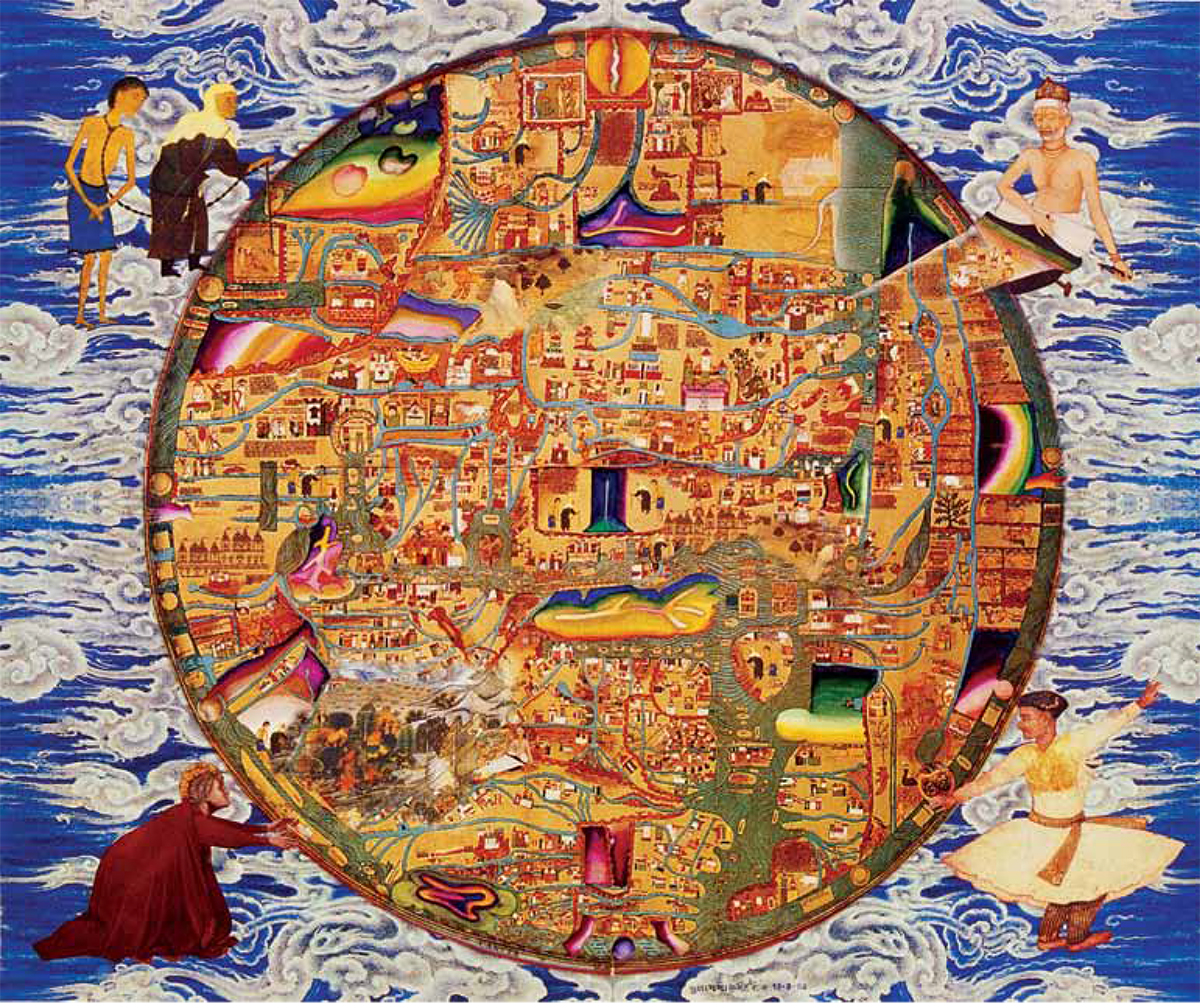

Sambrani’s perceptive analysis and insights present a complete picture of Sheikh’s stature as a pioneering Indian artist, the influences that shaped him and the important milestones during his storied literary and artistic career spanning over five decades. Furthermore, in short essays, three scholars dwell on the specific aspects of his later work. Terming his engagement with medieval mappae mundi (mappae, in Latin, means map or maps and mundi, plural of mondo, means world or worlds) as an attempt to “fashion an image of the world in which the depredations of colonialism and its legacies of violence can be rethought,” Cóilín Parsons shows how Sheikh “refigures medieval maps as the foundation of a resistant visual language that seeks to de-reify the process of the creation of the nation-state, with its attendant ethnic and national violences.”

Marcia Kupfer picks a term from the Indian classical music, jugalbandi, to exemplify another aspect of Sheikh’s artistry: the juxtaposition and interplay of motifs traversing Asian and European histories of art that puts them in dialogue with one another. Kupfer, who has researched the history of medieval art with special focus on pictorial narrative, historicises Sheikh’s orchestration of diverse traditions — a recurrent cartographic conceit that has informed a large body of his work since 2002-03 — with respect to western medieval and early modern representations of the world. Sheikh’s experimentation with new media and old forms of visual storytelling, and his return to an archive of art-historical references accumulated by him over decades, including his earlier paintings, is analysed by Karin Zitzewitz. “The shift in Sheikh’s work, or perhaps just the new sharpness with which he enunciates his vision of culture, can be traced to the changes in political discourse and social life in his home state of Gujarat since the devastating riots of 2002,” she writes.

At Home in the World: The Art and Life of Gulammohammed Sheikh

Edited by Chaitanya Sambrani

Tulika Books,

Published in association with Vadehra Art Gallery

Rs 4,500, pp. 464

Earlier this year, some of Sheikh’s works were part of a show “In The Light Of,” curated by Gitanjali Dang, at Gallery Ark (January 29-May 15) in Vadodara, which was founded by Seema and Atul Dalmia in May 2017. The show travelled to Sakshi Gallery in Mumbai on October 14 and will be on till November 18. A book of his writings on art and artists, Nirkhe vahi Nazar, has recently been translated from the original Gujarati into Hindi by Kiran Singh, and published by Raza Foundation and Rajkamal Prakashan. The book, which is illustrated in BxW and colour photos and works by painter and draughtswoman Nasreen Mohamedi, carries Sheikh’s heart-wrenching tribute to her. He writes about her simple lifestyle, her self-effacing and friendly nature that endeared her to people across all strata, her practice as a photographer, her struggles with the same disease two of her elder brothers had succumbed to, her fortitude, and devotion to art in the face of death.

Installation view, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Fatehpur Sikri series (1970). Image credit: For In The Light Of, Gallery Ark. Photo: Anubhav Verma

Installation view, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Fatehpur Sikri series (1970). Image credit: For In The Light Of, Gallery Ark. Photo: Anubhav Verma

Installation view, Gulammohammed Sheikh, The Legislative Assembly, Chandigarh (1966) and Fatehpur Sikri series (1970). Image credit: For In The Light Of, Gallery Ark, Photo: Suguresh Sultanpur

A book of Sheikh’s writings on art and artists, Nirkhe vahi Nazar, has recently been translated from the original Gujarati into Hindi by Kiran Singh, and published by Raza Foundation and Rajkamal Prakashan.

A book of Sheikh’s writings on art and artists, Nirkhe vahi Nazar, has recently been translated from the original Gujarati into Hindi by Kiran Singh, and published by Raza Foundation and Rajkamal Prakashan.

Through this interview, I attempt to take a holistic look at one of India’s finest artists, who has greatly influenced contemporary art’s engagement with hybridity, and whose explorations into pluralism achieves special significance in the polarised and vicious times we are living in. Most of the questions have been formulated after sifting the facts of Sheikh’s life and work from Sambrani’s descriptions of the artist and his times. It’s tough to encapsulate a richly lived life like Sheikh’s in a single interview. However, I have attempted to touch upon as many facets of Sheikh’s life as possible and hope that it gives the reader a fair sense of the many worlds Gulammohammed Sheikh sails around. Since the interview delves into several aspects of his practice that he has spoken at length about elsewhere, some of Sheikh’s answers reproduce, in italics, the texts of the original interviews/pieces, with a mention of the source in the end.

Excerpts from the interview:

Nawaid Anjum: Your 1970 photograph of Fatehpur Sikri, along with Mohamedi’s, provided the framework and the curatorial premise to Gallery Ark’s show, “In The Light Of”. Could you elaborate on the story behind these images in the light of your friendship with Mohamedi, whose work — which is all about absence, inwardness, silence and shadows — has evoked global interest and attention over the last decade? Do you see photography as an essential part of her distinctive aesthetic approach and artistic evolution, and as an art form that illuminates the principles at the heart of her paintings?

Gulammohammed Sheikh: The story of the Fatehpur Sikri photographs is plain and simple. We (Nilima, then Dhanda, Purushottam Dhumal, Nasreen Mohamedi and I) were in Fatehpur Sikri on a Sunday in the summer of 1970 as tourists. It was a day off from the Smithsonian Workshop on printmaking organised by the United States Information Service in which Nasreen, Dhumal and I were participating. I carried my Asahi Pentax K2 loaded with a Kodachrome roll but also carried a bxw Kodak (or Ilford) roll; Nasreen had her Nikormat, and Dhumal his Minolta. We all went our own ways photographing the architecture and the surrounding environment for an hour or two. If you look at my photographs closely you may find shadows falling exactly below the surface of each object or building denoting it was mid-day. I took a number of photographs from the 36 exposures that each roll provides. So, it was nothing unusual if two artists were to find themselves near the same spot a couple of times during a circuit of six dozen shots. It can however be seen that our approaches were quite different. Nasreen, with her minimal aesthetic, was interested in the bare form of a floor or detail of a corner. I was on the contrary more interested in the entire architectural environment as a whole. Nasreen’s was an a-historical view whereas the historical is part of my make-up.

Nasreen’s photographs were printed and exhibited all over, while I printed mine decades later. There was a little similarity between two or three snapshots which I shared with Shanay Jhaveri who was part of the curatorial team of the Nasreen Mohamedi show at the Met Bruer, New York (after the retrospective at Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid). The Guild in Mumbai made a portfolio of ten of my Fatehpur Sikri prints which triggered the imagination of Gitanjali Dang to conceive the exhibition.

I had not felt the need to write on Nasreen’s work or photographs, since they had been written about in her catalogues and elsewhere, including by well-known critics like Geeta Kapur.

It would be relevant to note here that it was quite common for artists in Baroda (and elsewhere?) to own cameras and experiment with creative photography. It was part of the Graphic Arts discipline taught at the Faculty of Fine Arts where I taught art history. In fact a group of us Baroda artist-teachers: Jyoti Bhatt, Jeram Patel, Vinod Ray Patel, Feroz Katpitia, Vinod S. Patel and I, besides Narendra Mehta who taught photography at the Graphic Arts Department, exhibited our photographs as art works under the title of Painters with a Camera (Jehangir Art Gallery, Bombay,1968).

_ITLO.jpg)

Gulammohammed Sheikh, Fatehpur Sikri 7, (1970), In The Light Of, curated by Gitanjali Dang. Photo courtesy: Gallery Ark

(From left) Nilima (then) Dhanda, Purushottam Dhumal and Nasreen Mohamedi, Fatehpuri Sikri, 1970. Photo courtesy of Gulammohammed Sheikh

(From left) Nilima (then) Dhanda, Purushottam Dhumal and Nasreen Mohamedi, Fatehpuri Sikri, 1970. Photo courtesy of Gulammohammed Sheikh

Nawaid Anjum: As a painter-poet-pedagogue and an art historian, you have seamlessly transitioned between two worlds: the world of canvas and colours, and the world of words. How do you approach both these processes? What determines your choice of form? If painting allows you to look at life through art and look upon it as a catalyst to create concepts for living, what do writing poetry and prose offer? Can writing be as rigorous or as cathartic as bringing a painting into being?

Gulammohammed Sheikh: The practice of all art forms does serve the purpose of offering ways of living. Writing, too, brings the world into being as does painting, but perhaps different in the way that it is articulated. The practice of art emanates from complex inner callings, hence they are not necessarily cathartic, unless of course if such a need arises. The world of paint and the world of words are not necessarily antagonistic either (as is firmly established by the traditions of Indian painting) yet each chart simultaneously, parallel or conversely, independent paths. Despite the differences of form, paint and words can embrace a common content but the substance of the content gets invariably transformed in these different forms. In my case, the paintings of a lone horse in a desolate ‘landscape’ in my early years (1960-63) carry an intensity to unravel unknown fonts of desire as do the poems of the same period burning with angst and ennui. A seminal painting of the late sixties ‘Returning Home after Long Absence’ (1969-73) deals with multiple and diverse imagery born of different sources. And the series of autobiographical writings in Gujarati Gher Jataan (‘Returning Home’) from 1969 onwards also deals with multiple genres of an essay, a narrative or a poetic meandering. I wrote earlier about the choices: ‘The world as it came to me, almost invariably manifold, plural or at least dual in form. In art, painting came in the company of poetry and images from life lived, from other times, from paintings, sometimes from literature, and often from nowhere, emerging together through scribbled drawings and words. The multiplicity and simultaneity of these worlds filled me with a sense of being part of them all’. — (‘Among Many Cultures and Times’, in Carla Borden, Smithsonian...).

Nawaid Anjum: The firmament of modern Indian art is studded with the likes of Bhupen Khakhar, Gieve Patel, Jogen Chowdhury, Nalini Malani, Nilima Sheikh, Sudhir Patwardhan, Vivan Sundaram, Ebrahim Alkazi, VS Gaitonde, K. G. Subramanyan, FN Souza, SH Raza, Jeram Patel, Krishen Khanna, and MF Husain et al. Having emerged on the art scene after Independence, they shaped the 20th century art in the post-colonial India in their own ways. Do you see yourself as a product of your time and your initial works as responding mostly to the Progressive Artists in Bombay, like Husain and Souza, with whom you had close associations?

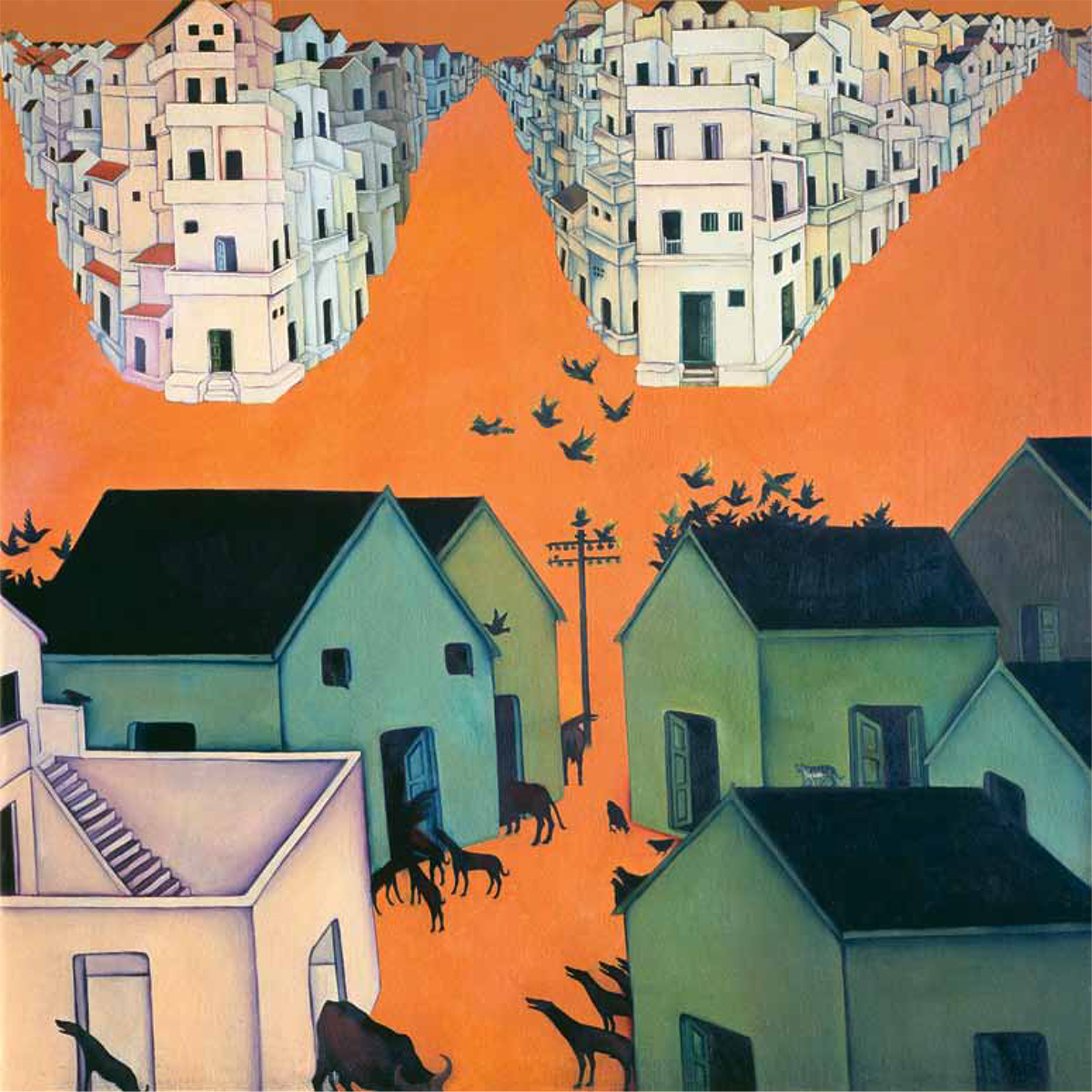

Gulammohammed Sheikh: Each of these artists dealt with figuration differently. A majority of them remained within the orbit of ‘International Modern’ in comparison to our generation (especially Bhupen, Gieve, Sudhir, Nalini, Vivan, Arpita, Jogen, later Nilima) charted a path quite different by drawing upon contemporary realities of the times and places in which we lived. I have said elsewhere: We were all trained in the international modernisms of Cubist, Expressionist or Abstractionist modes practiced by the artists of the previous generation (i.e., the Progressive Artists) you have cited. Our own generation, including the artists of the Group 1890 (formed in 1962) that I was a part of, also began their careers with one or the other kind of these modernist options...We wished to disinherit those tried options and the binaries we were saddled with, because our concerns and orientations were quite different. It was a question of finding an alternative visual language,....My interest was to cull useful devices from diverse traditions, from the Sienese to the Mughal, to render contemporary realities including current politics into a viable pictorial alternative. We consciously aimed at art foregrounding the human image without any sense of hesitation or guilt of it being dubbed 'illustrative'. Yes, it was a chosen form of the hybrid to stand against notions of purity, and seek a divorce from the dilemma of belonging to either the 'modern' or 'traditional'. (Interview with E.V. Ramakrishnan, Frontline, July 2, 2021)

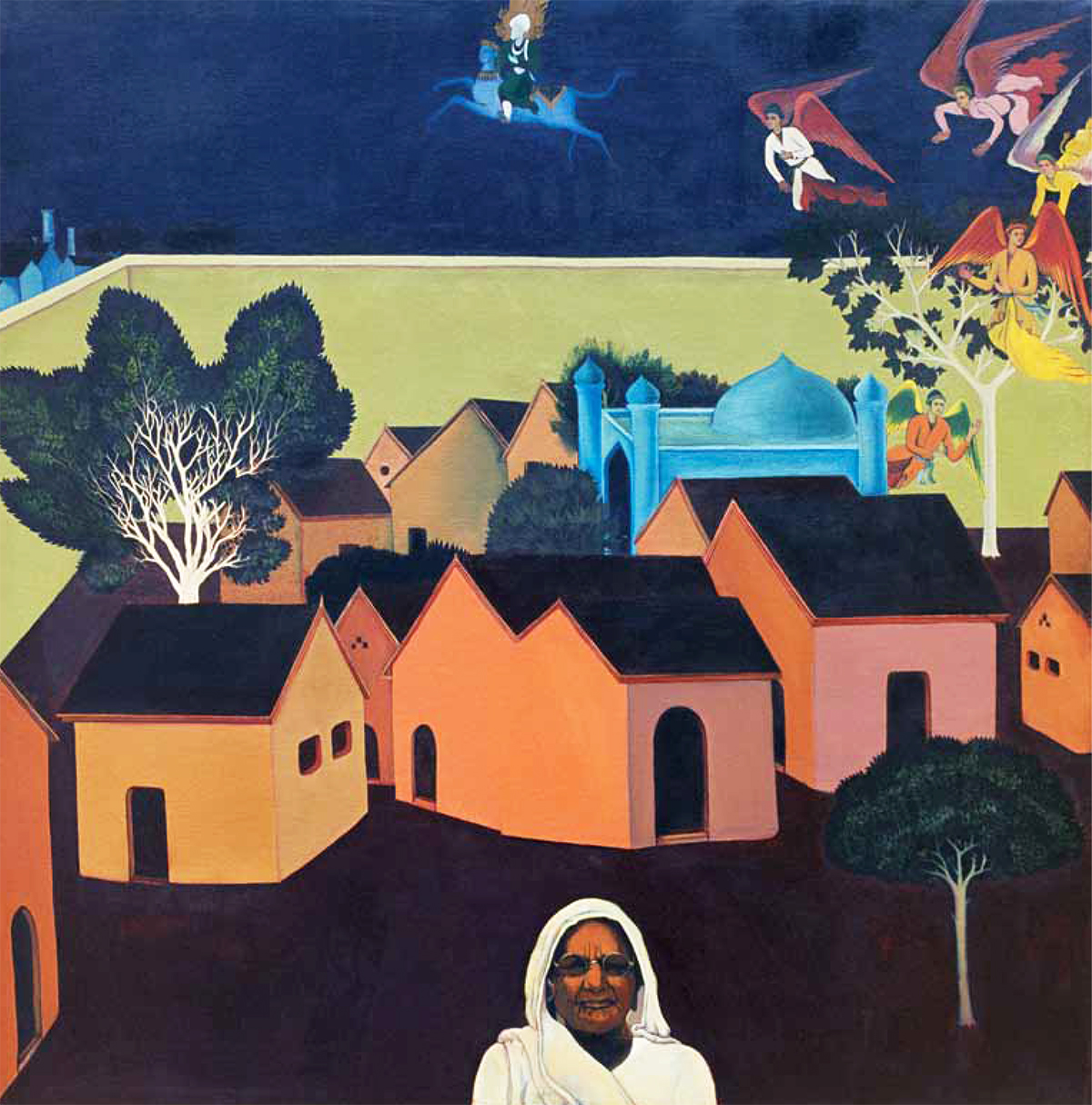

Returning Home after Long Absence, Gulammohammed Sheikh, 1969–73, 122 x 122 cm, oil on canvas

Nawaid Anjum: You spent your formative years in Surendranagar, a place that you have held onto as a talisman of belonging, as Sambrani writes in At Home in the World. As the place of your family origins, it forms an inseparable part of your character because it was here that you discovered the joys of friendship across faiths, a passion for poetry and art, and an abiding sense of being part of a multi-form culture. Could you talk about your cultural, linguistic, literary, religious, mystical and artistic encounters in Surendranagar that shaped your sensibility?

Gulammohammed Sheikh: I recall that the childhood I spent in Kathiawad was full of stories of different kinds. Many were related to belief systems. Most children learnt their beliefs at home, but we rarely talked about these to each other. We knew little about others’ beliefs, thus losing out on seeing ours from others’ perspectives. The non-sectarian educational system of the Nehruvian era was designed to exclude reference to religious practices. Our information or understanding of others’ beliefs was derived from observing public functions and festivities, often from a safe distance, so we cooked up stories about each other. Yet there existed a kind of mutual respect for each other’s beliefs despite the distance. This view grew out of the common belief about the presence of the ‘sacred’ in certain sites and practices. It was not unusual for a Hindu crowd to stop near a mazaar (mausoleum) of a saint, even if it was a religious procession, stop the bands, pass quietly and then restart. The marriage procession would do the same. In the Geban Shah Pir dargah (shrine) in Wadhwan I saw many families, not just Muslims, who came there to pay homage to the saint or have their children pass under the hollow of a tree near the shrine to get the blessings of the Pir. Or they tied a little doll-like figure at the shrine. There are many places where such practices are observed. Similarly among the Muslims there were practices which clearly referred to other belief systems. There was a Muslim singer called Abhram Bhagat who sang bhajans (devotional songs), mostly religious, mostly Hindu. In those days one could hear his voice everywhere: at public functions, in restaurants and even in cinema halls! Nearer home, I would notice practices within my own family which today would be branded un-Islamic. In other words, following multiple belief systems was a part of popular culture.

Yet, there was also a curtain drawn between the communities at a certain level. I had Hindu and Jain friends in school and I would go to their homes but it was difficult to break the barrier of witnessing the garba (dance on a religious festival) in their locality. Hardly any Muslim would be seen in that space. There was no question of a non-Muslim ever visiting a mosque either. So, while a sense of the sacred made people respect each other’s faiths, the divides remained.

For me, to opt for Sanskrit as a second language (the option of Persian had been discontinued) at school was an opportunity to learn about scriptures and literatures of non-Islamic origin. Writing poetry in my mother tongue Gujarati added to that. In this way I became more familiar with belief systems other than the one into which I was born. There was no possibility of learning Arabic: one only learnt to recite the Qur’an from the madrasa (religious school) without understanding a word. (From Kaavad; Home, Travelling Shrine: Home, 2008)

Page

Donate Now

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

.jpg)