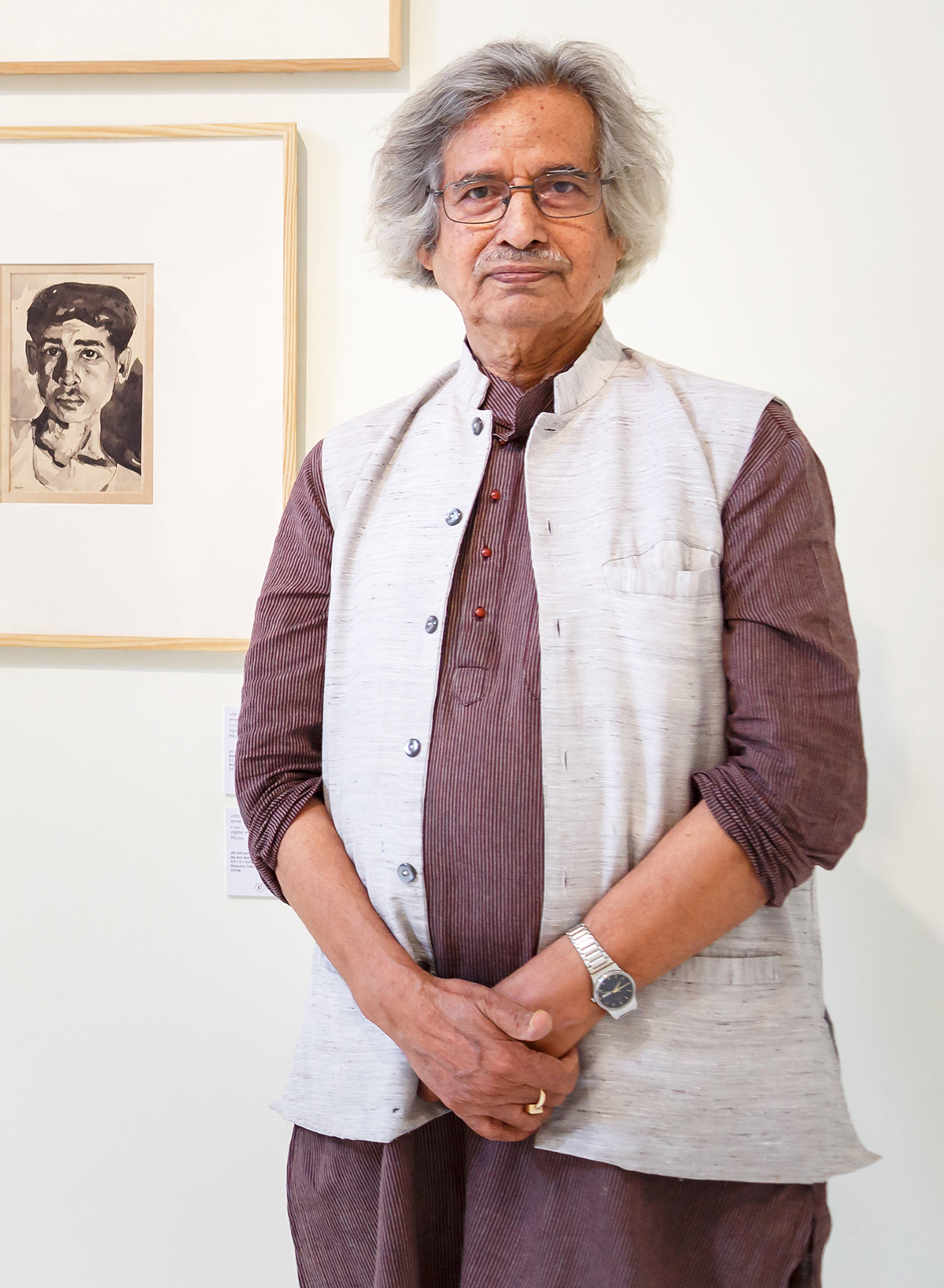

Artist Jogen Chowdhury. Photo courtesy of Emami Art

‘My works have introverted quality with intense feelings. When I paint or draw, I also establish a relationship with my subjects. As a social being, it becomes natural. It serves multiple purposes’.

Any work of art — abstract or real, old or contemporary, small or large — ultimately needs to have transcendental qualities. It’s a dictum Jogen Chowdhury, one of India’s most dynamic and multi-faceted modern artists, swears by. His works, spanning over six decades and exploring the enchantment of the everyday, are all intimations of transcendence. Not too long ago, while curating Chowdhury’s retrospective show “Reverie and Reality”, held at Emami Art, Kolkata Centre for Creativity, between September 20 to December 7, 2019, Ranjit Hoskote wrote how the artist “invites us to speculate about the inner lives of his protagonists: the concupiscent or estranged couple, the tonsured monk, the dreaming boy, the aging libertine and the courtesan whose limbs have lost their tautness.”

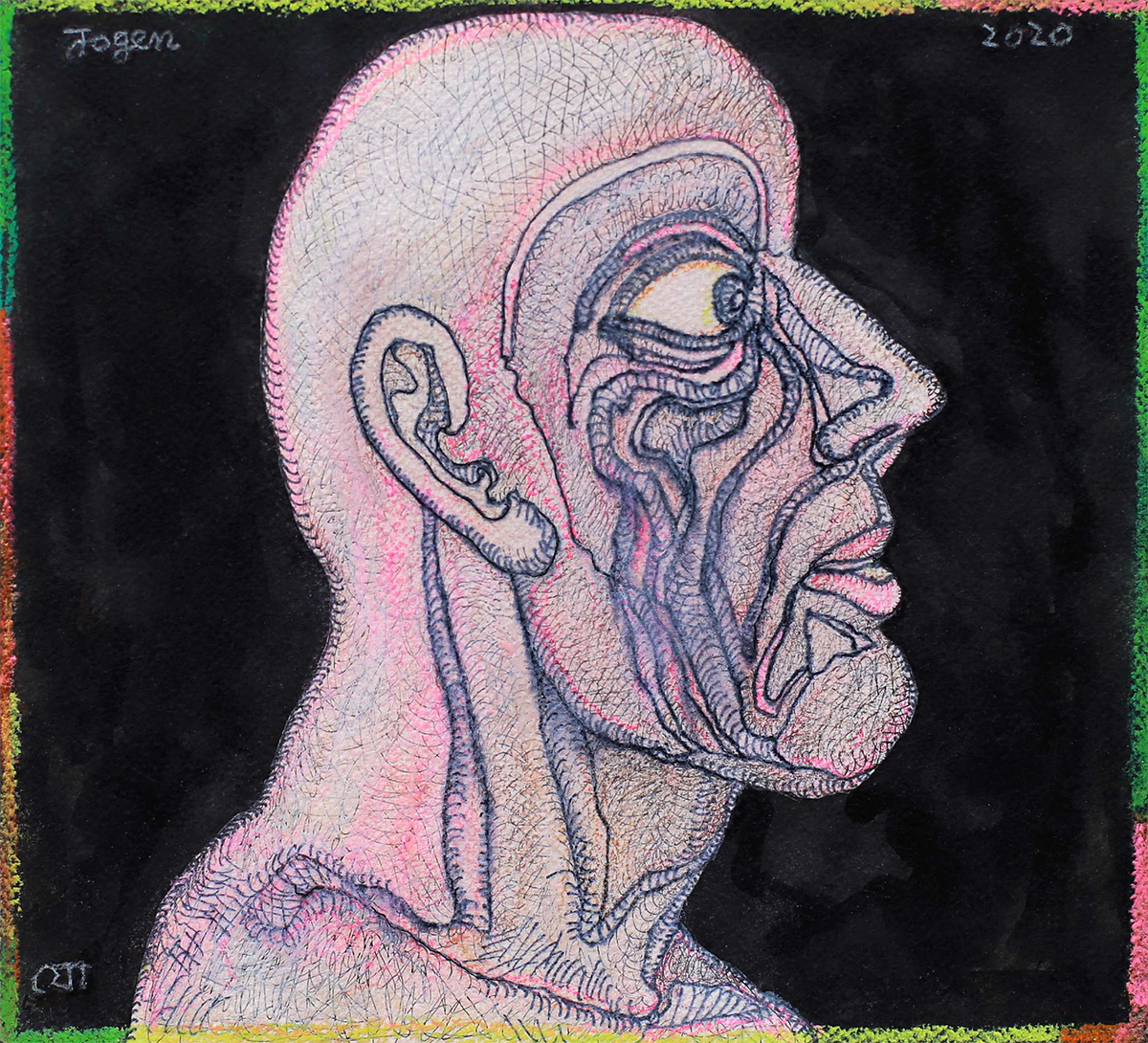

In a note to mark his solo exhibition, “An Unfinished Poem”, which opened at Art Exposure in Kolkata on December 18, 2020 and will be on till February 6, Chowdhury, who turns 82 on February 15, reiterates the same: the need for the works of art to have a transcendental quality. Made over various periods of time and employing different subjects, styles and mediums, these works show how Chowdhury continues to be deeply engaged with the manner of living, the minutiae of his milieu, the general “drama of life” unfolding around him: intimate portraitures, paintings/drawings of man, plant and animal life. With some of it made during the lockdown, these works seem to reiterate another avowed aspect of Chowdhury’s art practice — how the “distortion of the painted figure and posture is a deliberate ploy to show the complexity that exists within a man and in his relationship with the environment and the world,” as art critic, curator, collector and author Ina Puri underlines in an incisive essay that features in the catalogue for the show. “The recurrent theme of gruesome wounds and mangled limbs portray his agony yet again in the vividly painted images of severed fingers or that of a nude body with a gash across its torso. Disturbing yet riveting, these images are a powerful comment on the recent history of our country, visual narratives that lastingly sear the imagination of the viewer,” she writes.

Bewildered, Mixed Media on Paper, 25.3 x 28 cm, 2020, Art Exposure

Lonely Woman, Pen and Ink with Colored Pastel and Pencil on Paper, 19 x 18.50 cm, 2016, Art Exposure

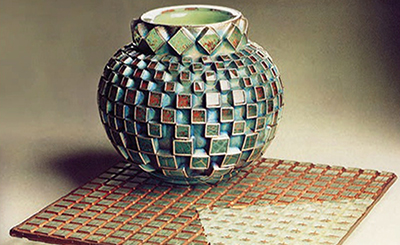

One of the subjects that have repeatedly occurred in Chowdhury’s paintings, he writes in the catalogue, is the man-woman relationship and the innumerable components surrounding it. “I am fascinated with the complexity, the sensitivity and dramatic element it offers,” writes the artist, who strives to make his works intense, sensitive and ‘living’ in the sense that it contains the “elemental qualities” of a work of art. “The pictures depicting faces of men and women reveal weariness as if the lovers of yesterday are long past their prime and their romance is now like a dried flower discovered between pages of a book of poems. The spirit of an invisible city lurks in the background, unseen but present, the brutal smoke-spewing factories, perhaps, the crowded metropolis heaving with multitudes of people trying to go through the motions of life, in the hope of a better tomorrow,” writes Ina Puri in the essay. For Chowdhury, who lives and works out of New Delhi, Santiniketan and Kolkata, it is important that everyday objects should be made artistic. “This is necessary for the growth of an understanding of art among the public — and people can be exposed to art through them. An object of use, like a bed, a light stand, pots, spoons, textiles, available in most households, may have artistic form, colour, line, etc and can give pleasure to the person who uses and looks at it,” he writes.

A new show ‘Proximate Paths’ to be held at Akara Art, Mumbai, from January 14 till February 28, 2021, will look at Jogen Chowdhury’s introspective self-portraits and satirical renderings of Bengal’s middle class, contrasting his style with another leading figure from the generation of figurative painters, Bhupen Khakhar, who found inspiration in the street, creating portraits of barbers, tailors and watch repairers. The show will explore how the two artists were drawn into a “larger movement towards politically engaged forms of narrative figuration”.

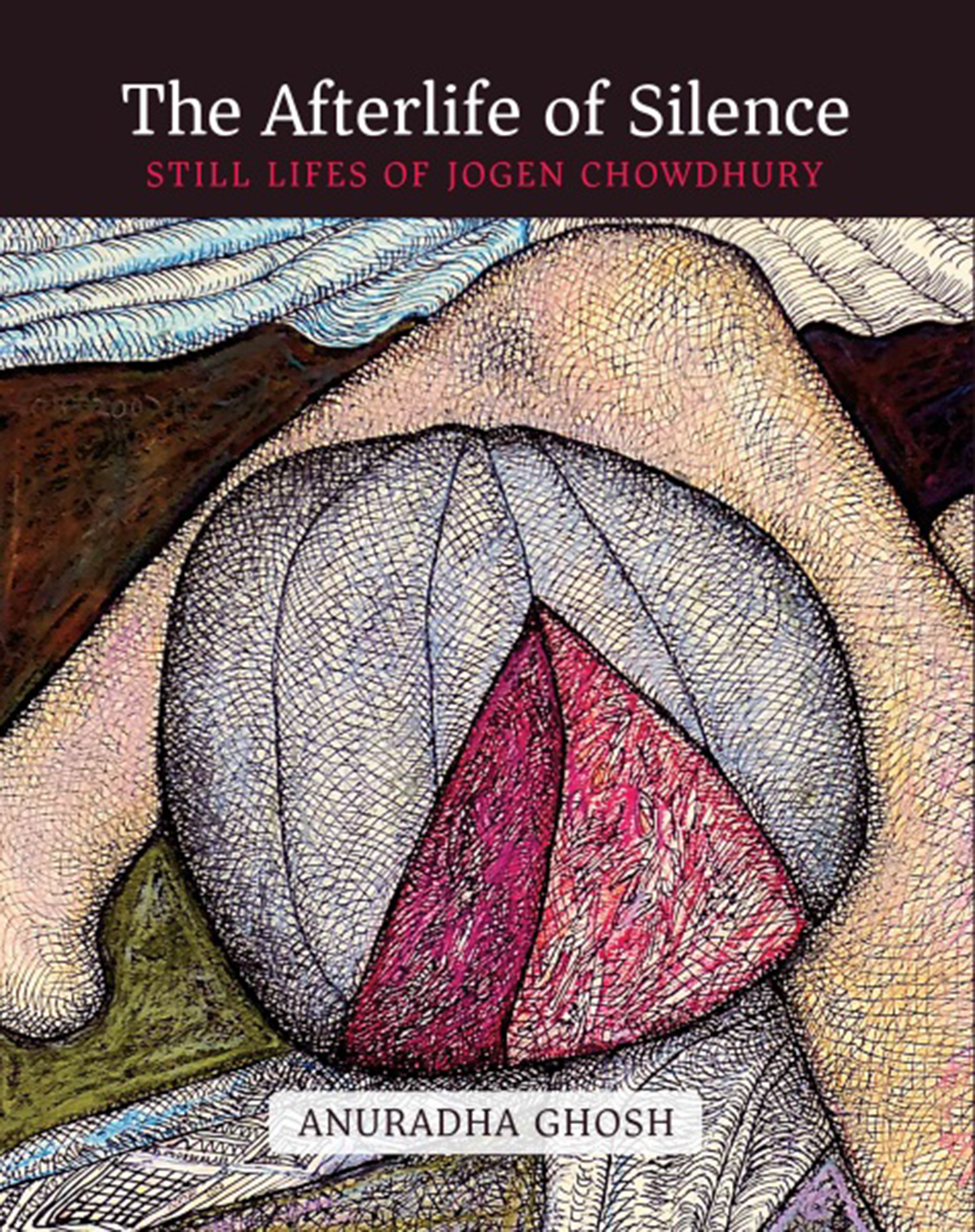

In a new book, The Afterlife of Silence: Still Lifes of Jogen Chowdhury (Niyogi Books, 2020), Anuradha Ghosh, associate professor of English at Dinabandhu Andrews Colllege, Kolkata, takes a deep look into Chowdhury’s still lifes. Ghosh writes elegantly on the arc of Chowdhury’s still-life works and how he is “principally concerned with the indoor world, the drama of the interior and the domestic.”

In this interview, Chowdhury talks about his early life, moving away from abstract art and finding his own vocabulary, his choice of form and content, why he made painting in ink, watercolour and pastel as his forte, the unmistakable sensual and scruptural feel to his works, and much more. Excerpts from the interview:

Nawaid Anjum: You are part of a generation of artists — along with Bhupen Khakhar, Gieve Patel, Nalini Malani, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Nilima Sheikh, Sudhir Patwardhan and Vivan Sundaram — that shaped contemporary Indian art, having emerged on the art scene in a newly sovereign nation and in a world coming to terms with post-modernism and post-coloniality. Most of these artists tended to approach their human subject by primarily focusing on the regional and the allegorical. How do you see your art being deeply enmeshed in, and informed by, the socio-cultural strands and elements of the time?

Jogen Chowdhury: My early life was much different than my other artist friends with whom I participated in the ‘Place for People’ show in 1981. When I was only nine years old, our family arrived in Calcutta from East Pakistan in 1948 as refugee leaving our ancestral home and finally settled in a refugee colony in south Calcutta. The social and political turmoil, the Left movements and, finally, the financial problem made our life difficult. However, side by side, we were busy with cultural and literary activities, dramas and Durga pujas and various social activities organized by newly settled enthusiastic people almost in all the refugee colonies. I was the organizer of a literary and cultural group and published our first literary journal of 16 pages called Nandimukh in Bengali in 1961. I graduated from the Government College of Art and Craft, Calcutta, in 1960 and got a job in Howrah Zilla School with a salary of Rs 125. I continued my art practice in my tiny studio of 10x10 feet, doing drawings on newsprints and paintings on pasteboards and I was quite happy. Calcutta was overcrowded with people and having regular political strikes, processions and meetings during those days, along with annual Durga pujas, film festivals, cultural and musical programmes, art exhibitions in Academy of Fine Arts, etc. Since my childhood, I was a keen observer of people, their gestures and facial expressions. I could feel their agony and happiness. My relationship with people and my environment/ambiance was deep and became part of my artworks.

Nawaid Anjum: In your work, you have defied trends and broken away from the prevailing conventions of the time, chiselling your own distinctive style, and forming a unique vocabulary of your own. For instance, at a time when most Indian artists were exploring the abstract, you chose to do figurative works. What has been your underlying quest behind this conscious choice?

Jogen Chowdhury: It is true that during the 1960s/1970s many of our major artists were fond of doing abstract art, thinking that it was ‘Modern’ and the ultimate expression of art. In fact, they followed the development of Western art flatly, ignoring creative possibilities that could happen with local elements and spirit of our society which should have been particularly interesting and significant. I always felt that India is rich enough for any creative person. The country has many complex and multifarious elements like past art and culture, folk arts, cultural and religious diversities, poverty, corruption — which can inspire a creative person to find new visual spirit and images.

I believe that abstraction exist also in ‘real’ forms, in the human figures or any other object. I do not paint realistically but distort enough to make it acceptable to me in respect of form, colour, tone, lines etc. and ultimately a sense of infiniteness, spirituality or magic quality need to be brought to so-called real form to bring the work to a ‘transcendental’ stage. It happens to the artists when they are creatively engaged and in a stage of trance. It happens to all creative people like poets, dancer, musicians and also artists and painters.

I think people and image-making were always major parts of our visual art, and it will continue to stay so in the future too. Of course, it will not be the same as now in future and be created through various new media, techniques and styles.

Wounded, Ink and Dry Pastel on Paper, 29 x 21 cm, 2002, Art Exposure

Nawaid Anjum: As an artist your forte has been painting in ink, watercolour and pastel. In your line drawings, you have explored the soft curves and angularities of contorted bodies, using ink combined with pastels. In such works, you construct volume by modulating light and shade. Your use of the technique of crosshatching in your ink and pastel works, which allows you to develop an illusion of middle tonalities, has become the most discernible feature of your style. How did you arrive at this style? To what an extent was this influenced by the European tradition, especially since you went to study at the Beaux-Arts de Paris in 1967? Does form drive the content of your works? How do you look at the relationship between form and content?

Jogen Chowdhury: It is true, from the beginning of my art practice, I realized that I have the ability to see and feel an object or human figure with its volume and modulation, probably that is my inborn capacity. It helped me to draw or paint with volume and modulation of a figure or any visual object. I develop crosshatchings when I was in the upper class of art college. I started giving shades with crosshatchings while doing pen & ink works. It started in a very casual manner and, finally, this technique is being used by me creatively to make paintings on paper, along with pastels and watercolours. I seriously took it as a technique since 1968/69 when I executed my series of paintings in pen and ink on paper called ‘Reminiscences of Dream’ in Madras. Since then I have executed hundreds of works in this technique and have made some major artworks like Tiger in the Moonlit Night, Life –II, Man 1980, Her Silver Throne, Wounded, and many more.

Couple Life-2, Ink & Pastel, 154x152 cm, 1976

During my stay in Europe/Paris during 1965-1968, I had chances to visit a number of art galleries, museums and churches inEngland, Holland, Germany, Italy and France and I could also see numerous past and contemporary European arts which were most educating for me, besides our classroom teaching. I was appreciative of all great artworks but not overwhelmed; it rather helped me to ascertain my position as an Individual artist who was in quest of a personal language of expression in art. When I returned to India in 1968, for about a year in Madras, I was not able to do any artwork. During that period, I wrote a long article in Bengali on what I should do as a young artist.

I think ‘form’ and ‘content’ both are important parts of an artwork. In visual art, ‘form’ takes shape out of the visual objects, figures or structures, while “content”comes from the imaginative mind and experiences of the artist or the creator. For visual art, ‘form’ is essentially important for an artwork, it can be abstract or real, but should have ‘transcendental’ elements in it. But qualifying the validity of a ‘form’ or ‘space’ again depends on the able mind or intelligence of the artist or creator to measure it. In a valid abstract artwork, ‘form’ itself is content.

Page

Donate Now

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

.jpg)