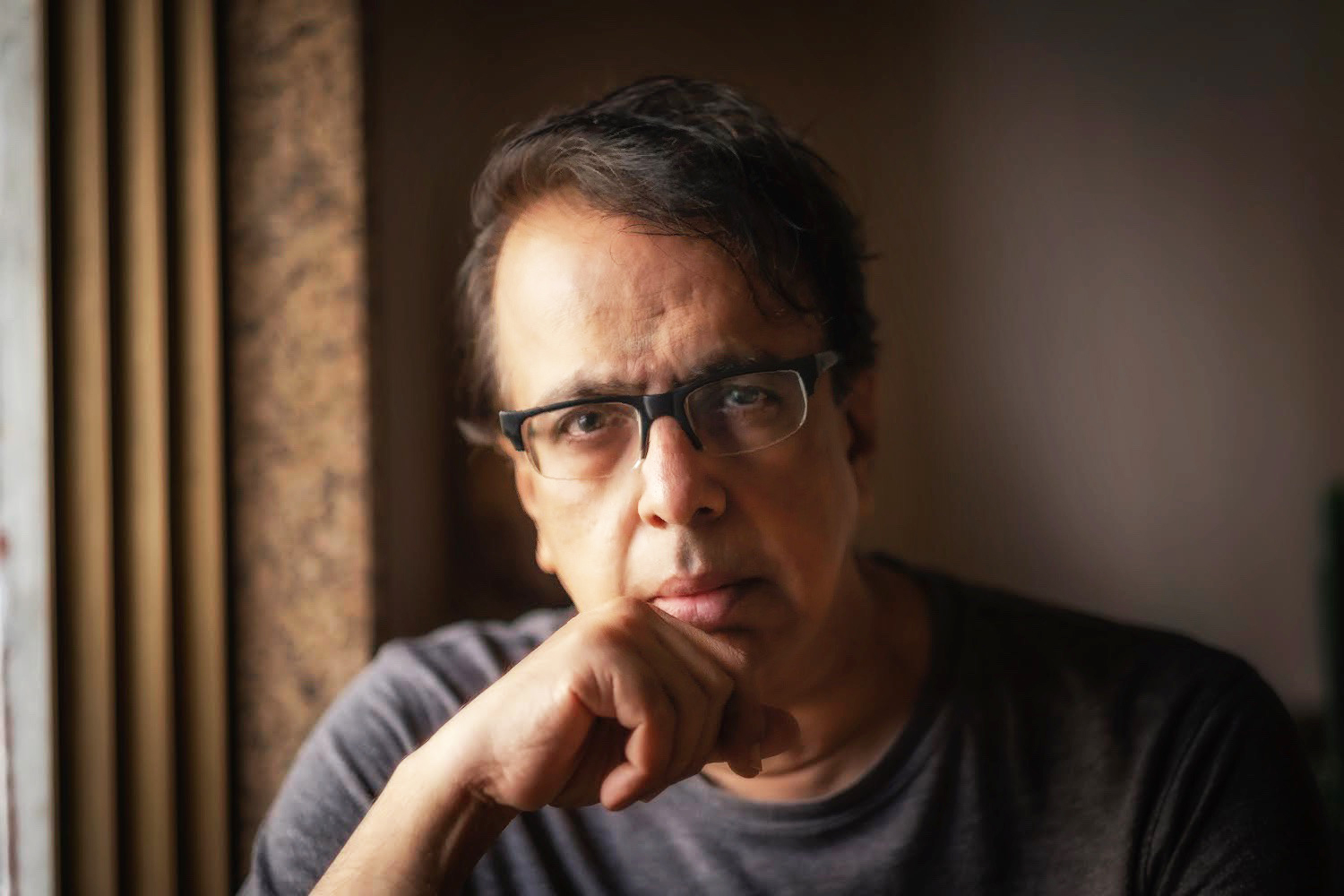

Filmmaker and screenwriter Ananth Narayan Mahadevan

The director and screenwriter on why making a film in India is more about creating a big consumer commodity and less about following a creative pursuit; why despite this he swears allegiance to pure cinema; and why the funding studios should do a 360-degree turnaround on their vision of the cinematic process

Success and What it Means To You Now

Padmaja Challakere: In earlier interviews, you have spoken about what sustained your energy as an actor, film director, and screen-writer for four decades. The simple secret, you said, is that you are “in love with your work, with the camera, and with movies” and that is why, despite all the obstacles, you have “kept the momentum going.” You defined success as being about “the pursuit of excellence”, about “creating something noteworthy,” making a film “that is counted among the best,” “to learn constantly,” and “grow as a director from film to film,” and not fit in with the formula of the Bollywood box-office formula movies and their obsession with commerce and sensational manipulation of audience emotion: “I will not fall in line with something that is mainstream, something that is crassly populistic.” In 2000, you bid goodbye to the Bollywood movie industry, and struck out boldly on a different path-towards making “meaningful cinema” or “content-oriented cinema.” Initially, it was a struggle to get exposure at International Film Festivals for your earlier independent films like Doctor Rakhmabai (2016). But your recent films, most recently, Bittersweet (2020) has received many accolades, a standing ovation at the IFFI in Goa, and garnered world-wide recognition from the international film-festival audience. Your films have become more and more urgent, more concerned with the terrible crimes and cruelties of our world today.

A still from Bittersweet

Your recent films Gour Hari Dastaan: The Freedom File (2015), Mai Ghat: Crime No 103/2005 (2019), and Bittersweet have been tremendously successful in the International Film-festival circuit. What has changed? How would you define success at this point in your cinematic journey? What does “success” mean to you now? Also, do you think that the cinema audience has changed?

A still from Mai Ghat

Ananth Narayan Mahadevan: Frankly, the term “success” has been cautiously relative and mischievously elusive. Yes, I have been successful [personally] in foraying ahead with the kind of cinema I wish to create…from the experimental Staying Alive (2012) to Red Alert: The War Within (2010), Mee Sindhutai Sapkal (2010), Gour Hari Dastaan, Rough Book (2016), Doctor Rakhmabai and now Mai Ghat and Bittersweet. It has been a decade of pushing my limits as a filmmaker and drawing myself out of one comfort zone after another. My personal growth as a director imparts a sense of ‘success’, but the world-at-large [despite the accolades and festival selections] continues to deny me that one thrust which could make a big difference to my efforts. For instance, how often do I hear that my films [Doctor Rakhmabai, Mai Ghat, to be precise] were in the final moments of reckoning for the National Awards and for some inexplicable reason, sidelined at the last moment by someone with a different agenda. The near hit-n-miss at the Oscar selections for representing India over the years isn’t funny either. Though this has not dented my appetite to relentlessly pursue cinema of quality, it does leave you with a deep sense of remorse, something almost like a conspiracy theory that you are forced to subscribe to. Audience tastes are difficult to decipher. Whilst a majority of the Indian viewers [often dismissed as “the masses”] still prefer to give their grey-cells an indefinite break to indulge in formula films, there is a discerning audience that decries the “leave-you-brains-at-home” syndrome and reiterates that “enough is enough”. But they aren’t enough to galvanize a tribe of filmmakers who unfailingly aim for the global market. Hence our works face an uphill task in trying to convince distributors/digital platforms and self-appointed high priests of the box-office, about the need to awaken audiences from slumber and give them a taste of something different. Having said that, let me affirm that I am not against entertaining cinema [who doesn’t love a good chase?] but the utter disregard for logic , for characterization and for sensibilities turn these “entertainers” into more of “circus acts” than exercises in movie-making. India with its myriad economic and literacy disparities will almost always fall for this “blockbuster” trap, and in the process, give quality cinema a lazy glance. The pandemic has affected another distribution outlet, one that is subscribed to at home, but I am afraid that these digital platforms [I abhor the term ‘OTT’] are also going the populist way and patronizing the very studios/banners that have spread the formula virus. It’s akin to the mushrooming of multiplexes that shockingly gave critically acclaimed cinema a backseat in favour of the hundred-crore extravaganzas. The vicious cycle continues. And I continue to wage this lone battle.

Journey from ‘Commercial’ to ‘Meaningful Cinema’

Padmaja Challakere: As someone who has watched your “mainstream” films, like Dil Mange More, Aksar, and Dil Vil Pyar Var, and enjoyed them, especially the song-sequences that so knowledgeably channel music and dance-sequences from older movies, I wonder if you wanted to make these anthologies or, as you called them, “retro-musicals” and were there sequences or directors that you were paying homage to or channeling or competing with? It felt to me that you were doing a sort of dark-humor take on commercial cinema, using the fantasy and the fable of Bollywood movie to move beyond it.

A still from Dil Vil Pyar Vyar

I also feel that there is a connection between your fictional “entertainment” movies and your non-fiction narrative “serious cinema,” like Gour Hari Dastaan, even though they are radically different.In both, you have an adventurous hero figure (like a Grail Knight figure) whose energy and passion brings about the rebirth of love or respect or tradition, either by choice or by chance. Would you agree? Or, are you a different kind of director when making a movie like Dil Vil Pyar Var and Gour Hari Dastaan? Could you comment on the convergences and divergences between the two kinds of films you have directed?

Ananth Narayan Mahadevan: Dil Vil Pyar Vyar was born out of the pressing need to graduate from directing on television to directing for the big screen. My pursuit of quality cinema had necessarily to be preceded by a middle-of-the-road venture. So, the concept of adapting published music [in this case, R D Burman’s] was amalgamated with four love-stories with the colour-tone of four seasons and woven into an entertaining tapestry of a musical-romance. Even as I fell in line with mainstream requirements, I was consciously garnishing it with sensibilities that would differentiate my effort from the regular box-office releases. The gloss and glamour quotient can be tempting, and I ended up making two more movies: Dil Maange More and Aksar, both of which were slotted as “musical hits”.

But I had to cry halt before I lost track of the kind of cinema I had initially set out to make. The credibility I earned from star-studded films like these stood me in good stead to convince producers to back some of the more serious efforts. So Red Alert and Mee Sindhutai Sapkal became possible, much to my relief. The attraction for true stories disguised as biopics was what led me to seek out Gour Hari Das, a freedom fighter who, ironically, fought for thirty years to obtain a freedom fighter’s citation. The “hero” of Gour Hari Dastaan is radically different from the hero of my earlier films. Those were manufactured characters, but Das is for real-flesh and blood, with a story stranger than fiction. His storytelling demanded honesty and conviction and an uncompromising approach, an element that I have gradually honed over the years with my subsequent films. These were real homages-not outlandish ones.

A still from Gour Hari Daastan

But the values that people like Das or Doctor Rakhmabai stood for have sadly eroded.They are a reminder of people made of sterner stuff. Yes, I am a drastically different director now. I have banished myself from the la-la land of Aksar/Aggar/Xpose’ and sworn allegiance to pure cinema, even if there aren’t half as many takers. Of course, I beg to disagree on one point — it’s grossly unfair to label pure cinema as “non-commercial or parallel cinema.” I would daresay that the formula movement is “parallel’ cinema, while the other side is the actual definition of cinematic language.

Emotion and Achieving Effect in Content Cinema

Padmaja Challakere: Since cinema is both an expensive medium and a collective endeavor that involves the work of screenwriter, the cameraman, sound-editor, actors, set-crew, how is emotion created in a scene in Gour Hari Dastaan? Of course, art-cinema does not overtly manipulate audience emotion with background music but could you speak about tonality in independent cinema? How is emotion evoked in relation to what you want to convey? Do you shoot a complicated shot many times? Is there anything you do differently technically to conceptualize your relation to how the character moves or owns the scene? And, how does budget or money come into play when retakes or edits are necessary, or in scene-editing or in how to sequence a complicated shot? Could you speak in relation to scenes in Mai Ghat or Bittersweet?

Ananth Narayan Mahadevan: A film like Gour Hari Dastaan has a recurring emotional thread. Not sentimental or manipulative. I make it a point to internalize the emotions of my characters rather than the chest-beating, loud methods that Indian cinema loves to wallow in. The subtlety meter is strictly followed, even if it is beyond the comprehension of a film critic [in this case one from The Indian Express] who callously [or was it a deep prejudice] dismissed the film as “slow”. For a film that narrates the story of a supremely patient man who waited for 35 years to earn his spurs, surely the pace can’t match that of a Bond film! These are the detractors who puncture your chances and morale and deflate the box office chances. But the overwhelming back-end response from viewers have given Gour Hari Dastaan long legs and it continues to move audiences even six years after its official theatrical release.

I generally do a mechanical rehearsal with my actors and then throw them into the ring to deliver the feelings in one take. Multiple takes only ruin the spontaneity and tend to make the actor stale. The complication in my scene is not from a particular way I choreograph a shot but rather the exploration of the complexities of the scene. In Gour Hari Dastaan, the pauses/silences are as important as the spoken word. The critic in question misread that as “boring”. How often do we offer pat rejoinders to other people in real life? We take our time to think. When that is reflected in my film, it adheres to a certain cinematic language I wish to speak. Also, I do not let technical excellence [the camera movement/prop exhibition/distracting costumes] overshadow the soul of the content. The elements of each department must fuse homogenously to achieve the whole effect.

As far as budgets are concerned, I let the script dictate the budget. No over-spending or needless wastage. My film is edited on paper, further saving edit studio time. It’s all a scientifically worked out schedule that has, so far, gone like clockwork.

Film Distributors and their Power

Padamaja Challakere: Could you speak about the gate-keeping function of distributors? What will it take for films like Mai Ghat and Bittersweet to premiere in theaters in India? Given that the exposure-time in the international film-festival circuit too is getting shorter and tighter, what would you like to say about the politics and commerce of film-distribution within the “meaningful cinema” or social-impact cinema industry? Please could you give us an insider’s perspective on funding and money for independent cinema-making?

Ananth Narayan Mahadevan: Unfortunately, cinema in India is a big consumer-commodity, and only on rare occasions a creative pursuit. The ROI [return on investment] is the first thing discussed by the Funding Fathers, rather than the content/plot. The star attractions follow. Films are green lit on ticking these two boxes alone. These infested waters at the origin flow down to the distribution network which attaches the commercial potential to the product and goes on towards a multi-crore marketing and exhibition spree. Cinema is not regarded as an artistic endeavor like in Iran, Austria, Germany, Sweden and other European nations. The [reverse] model of turning artistic successes into box-office potential in these countries is the prescription that needs to be looked at in India. But like I said, our cinema has been corrupted by the James Bond-Marvel influence and the moolah is all that matters now. “Meaningful cinema” [I prefer the label “cinema of substance”] is looked down upon with accusing terms as “art cinema”, ‘award-worthy cinema”, “festival film,” etc, actually giving the filmmaker a guilt complex. The independent producer today, with visions of breaking the glass ceiling, is at his/her wits’ end. We are often countered with the statement: ‘Your theme is all very well, but who’ll buy/distribute this? It just isn’t viable,” banishing our ideas in the embryonic stage itself. This random condemnation of innovation in cinema has often resulted in the world not taking our cinema seriously on every platform that matters, including Oscar considerations or festival selections. Yes, we have a huge reputation to repair.

Money, Budget for Filmmaking

Padmaja Challakere: In a recent interview, you said you wished some investor could give money to talented directors — your predecessors, like Girish Kasarvalli and Shaji Karun — money with no strings attached-so that they could make a film. We live today in the moment not only of self-congratulatory mediocrity but of a management culture that on the one hand announces its faith in originality and “out-of-the-box thinking” but, on the other hand, practices petty forms of accountability. As a film-maker, this means that one has to check a lot of boxes for a film to land with the international film-festival audience. Do you find that there are “types” and tropes that are called for in the content-oriented cinema, for instance, a strong female-lead? What kind of independent cinema producer do you envision, given that new independent releases do not last long theatrically?

Ananth Narayan Mahadevan: The late filmmaker Hrishikesh Mukherjee once told me: “Ananth, in this country you only have to be mediocre to be labeled “outstanding.” These words stuck to my mind and conscience. I just did not want to compromise on my filmmaking as I went on from one production to another. I had heard that Ravi of General Pictures, Kerala, used to blindly fund Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Aravindan to make the films they would not be allowed to make. The result is there for everyone to see: world beaters like Elipathayyam, Kanchana Sita, Thamp, Mathalukkal and many more. These films will outlive generations and not be erased from memory after a three-day opening weekend. As a filmmaker, I find myself becoming more ruthless with myself, encouraged by the masterful works of directors like Asghar Farhadi, Abbas Kiarostami, Alfonso Cuaron, Pedro Almodavar, besides the original auteurs like Bergman, Goddard, Truffaut, Fellini, De Sica, Kurosawa, Ray and others whose cinema had a deep influence on me. The target has always been to emulate these greats but the environment needs to be cleansed and educated. Unless the funding studios do a 360 degree turnaround on their vision of the cinematic process, I don’t see this revolution happening in India soon. Wealthy ambitions, crass politics and power-seeking individuals have turned the art of cinema into a cesspool. The very few daring names that have backed me over my past eight ventures are a Godsend and rare to find. To make the international community take me seriously, I need to tick three vital boxes: original content with an international appeal, but rooted in India, a subtle approach to complex situations, and an understated performance by writer, actors, camera, and director. Often this is incomprehensible to distributors and buyers on digital platforms who assume that the audiences aren’t ready for this drastic change. But the last year has exposed these very audiences to an international language of filmmaking, and they have subsequently rejected star-studded formula films that were touted as big earners. The writing is on the wall. The distributors should now start reading it.

Digital vs. Cinema

Padamaja Challakere: The movie-going audience has spent the last two years enmeshed in streaming; it has not begun to return to movie-theatres yet. What do you think about the new phenomenon of delivering independent movies through streaming platforms? What are your thoughts on the effect of the digital on cinema, on light, on the flattening effect of too much light?

Ananth Narayan Mahadevan: The streaming platforms are a default setting of the pandemic. Most of the films scheduled for a theatrical release were diverted mid-air during the Corona storm. The result was a sea-change in viewing habits. Audiences hit the lazy-bee button and unconcerned about big screen perks like giant visuals-sound etc, compromised on the viewing pleasure. The habit stuck when cinemas re-opened with the lowered costs of cinema going adding to streaming channel subscriptions.This defeats the purpose of cinema. It was meant for the big screen in a dark theatre. The form of cinema is not made for the format of television in a noisy room with bright lights on. Of course, one doesn’t deny the after-sales service of digital platforms. They help movies last, for viewing after theatrical exhibition wears off. Also, some films are made for a direct streaming release or prefer these outlets when denied a theatre format model. This has the effect of issuing a signal that only big extravaganzas will now qualify for theatrical attraction. This is another incentive to draw audiences back. Where does that leave the independent film makers like me, especially given the unexplained behavior of certain acquisition heads who stubbornly ostracize cinema of quality? It has become a race for survival of pure cinema in India.

Padmaja Challakere: Could you please speak about your tremendous success as a South-Indian in the Bollywood TV and Film Industry? It is fascinating to me, the number of languages you speak and think in.

Ananth Narayan Mahadevan: I guess I was fortunate that my parents moved to Bombay [in the 1960s] and set up my education here. The process that tutored me in English with Hindi and Marathi as second languages, along with the enriching experience of Hindi theatre, ensured that I did not develop a South Indian twang while speaking these languages. With both Tamil and Malayalam for mother-tongues, I found that at least five languages came to me easily, organically. The South Indian in Mumbai and its film industry is a rare occurrence and many South Indian heroes have found it challenging to be accepted in this West-North fold. Today, I make Marathi films with as much ease as Hindi films. The education in languages was all about taking your second languages seriously. My desire is to now make films in South Indian languages, having already enacted featured parts in Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada and Telugu movies.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated