The Rajbari at Bawali in Kolkata is steeped in old world charm. Photos courtesy of Rajbari

“There are no ghosts at the Rajbari,” I am categorically assured.

That’s sad, I think, as I enter the sun-washed courtyard that holds the rectangle of rooms together a floor above.

I would have loved to hear the whispers of generations of the fifty families that lived in the space; their laughter and petty quarrels, their intrigues and jealousies. It would have been grit for a book. They would have been music, too — ghosts floating past with only the tinkle of silver keys flung over the shoulder or anklets muted against silken sari borders to tell of their passing by. Rooms that sent out snatches of a song or a sobbing sarangi that melted into nothingness the moment the doors were opened. Ah, I tell myself, in this rich minefield of a fully lived decadence, I can only bemoan lost opportunities.

Others mined the space beautifully. Ray, for example. Yes, you heard right. Satyajit Ray was here. Camera, storyboard drawings and all. Watch the film Jalsaghar (1958) and you will see the terrace that once stretched across on one side, on which the zamindar, old, infirm and wrapped in sorrows of a lost past sits smoking his hookah. Watch some more, or fast forward the reel if you have no time for old black and white films even if the world calls them masterpieces, and you will enter a hall where Ray placed the two evocative and very dramatic scenes of the mujra that the zamindar organises. The halls gleam in soft chandelier lighting, glasses clink and catch the light, and at the far end from where the men, dressed in silks recline against scented bolsters, Begum Akhtar sits with her musicians and uncovers a ghazal, line by seductive line, through notes that rise like vapour to mingle with the smoke in the room.

Years later, Rituparno Ghosh would walk the corridors, decaying by now, the walls stripped of their shine, showing their bones through rotted flesh, and create celluloid emotions to replace the real ones stifled by time, as he brought Tagore’s Chokher Bali (1903) to life (in 2003).

All that remains of that episode is a series of framed posters that the house holds on to. You can live with them in room no 224, if, unlike my colleague who occupied the room during our visit, you do not feel intimidated by having Aishwarya Rai looking down on you as you drift off to sleep on a four-poster bed shielded within gauzy canopies. Rai will not scare you, but perhpas the other artefact in the room might ignite your imagination.

Though the Rajbari at Bawali has been completely restored, modernised, beautified and every vestige of decay has been scrubbed, rebuilt over and painted new, one last legacy has been lovingly preserved. It takes the form of a chest, a small, almost insignificant one that now stands quietly in room no 224. When he handed over the title deeds and the building of his ancestors dating back 250 years to the new owner, he also told him he was leaving behind a chest. Unopened. He had received it so, from his forefathers, and left it untouched.

They did ponder over whether it should be opened... the new owner and the soon-to-be-erstwhile one. The deal they arrived at was that if opened, the goods inside, precious or insignificant, delectable or sinister, would become the property of the new owner.

But neither made the move or took the decision, and now, for the hyper-imaginative visitors, or those fragile of courage and weak-hearted, the chest holds a mystery that can either fuel a story, or rob sleep.

But enough of the past. Let me take you to the present.

The courtyard of the Rajbari leads to the Thakurdalan, where once the gods were feted. Beyond that the lavishly appointed dining rooms, one private, with mahogany table weighed down with candlesticks and floral arrangements, and the other, a restaurant, bright, airy and inviting. The gods are not forgotten either. Every evening, at sundown, or when the guests are back from their wanderings, depending on which happens later, the gods are addressed through conch and bell and a ringing voice that chants from the holy texts, as the diyas glisten in the gathering darkness.

Oftentimes too, if they so desire, guests can feel as the zamindars did, and watch from the cool embrace of the verandah a floor above, a dance recital or music performance by hand-picked young talent who have been brought down from Kolkata for the purpose.

Opulence is a theme nurtured here, and the rooms, the flooring and walls, as well as the gardens reflect it. But nothing spelt the word as clearly as the fact that the residents of the Rajbari had access to their own water through two natural ponds. They still form part of the estate, and ducks and geese, perhaps descended from the older flock and thus luckier than their human masters, still waddle about and enjoy their share of opulence, undisturbed.

If the Rajbari is a visual delight today, worthy of the Award of Excellence bestowed on it by INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage), it is because according to its new owner, it has been a labour of love. A love that happened by accident. When, searching for spaces he could convert into a warehouse, a jute baron named Ajay Rawla drove through the crowded narrow lanes that led outside Kolkata where he lived, to Bawali. An old temple caught his eye, and he walked about to find himself in front of huge doors. Entering, the ruin that met his eyes lit an instant lamp of love. And a need to have and hold, as lovers must.

It was not an easy conquest. Many stakeholders from the 50 families had to be located, approached, appeased, and persuaded. But love crosses all barriers, and Rawla crossed them one by one through generous gifts of fish and misti, earnest conversations, on his many visits to homes across the region. When the deal seemed ready to be inked, he started buying the furniture. Cocoon, a store that dealt with old and reproduction works in wood, was his favourite haunt.

Then, just as his dream began to take shape, personal tragedy cut the ground from under his feet. It looked as if the Rajbari was doomed to fall to ruin after all.

Today, the Rajbari stands witness to the healing hand of time. Rawla has ensured the restoration remained close to the ethos of the place. To that end he got masons from Murshidabad to train with the Aga Khan Foundation, before embarking on rebuilding the rooms and the surrounding areas in manner and material that the original structure had been built with. Of course, much new work had to be done. Despite their princely ways, the zamindars had no knowledge of the comfort of en suite bathrooms; religion and habit prevented proximity to “unclean” spaces. The bathrooms, the plumbing and the appointment of each was a challenge that had to be met, regardless of cost and effort.

But much of Rawla’s love of the original shows up in columns left half plastered, and a wall of bricks that can be glimpsed from some angles from the courtyard, memories of what once had ignited his passion.

Making the experience complete is the food. Menus are set to the redolent meter. With meals that can hark back to the zamindar era with the Zamindari Thali, or the lighter but equally filling Satvik Thali. Rich mutton and fish dishes that are from traditional cooking have been recreated by the chefs, led by the disarmingly fetching Mrinalini, who ambushes diets with beguiling menus.

Rawla borrowed Mrinalini from a five-star hotel when he was faced with feeding the Duke and Duchess of York, who were guests at the Bari, and his close friend offered to request his niece to wear the apron at the Bari for the purpose. Today, Mrinalini and her mother, Debasri, reside there, in a suite at one end of the Bari. As a guest, you may meet them as you enter, in traditional Bangla saris, complete with bangles and jewellery, making you believe you have indeed taken a happy step and fallen into the past.

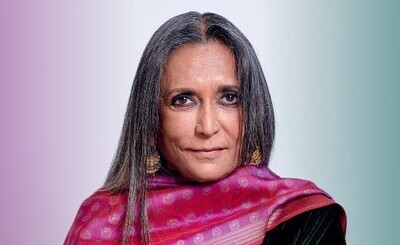

Other lucky “finds” for Rawla include Manoranjan Baul (above), an old man who would sing on local trains for his supper. Listening to the Baul, who entertains visitors at tea time, is an experience the zamindars must have taken for granted, but the discerning ear can not only delight in the words of wisdom but also in his knowledge of ragas, that he sings to the strains of the harmonium hanging around his neck, and the beat of the clappers and drums played by his assistant.

But that is not all. Outside the walls of the building is a world worth discovering. The villages around once supported the staff that worked for the Rajbari. Built on the Delta to the Hooghly, which flows nearby, the villages are dotted with ponds where the villagers now grow prawn and coloured and fancy fish for sale in the cities. A walk through is even more a walk through time... everyone knows everyone else, young men chat by the roadside as they ply toothbrushes against teeth and walk across to the nearest pond to complete the procedure. Village gods look out from tiny temples, and at the end of a leafy walk, a temple to Shiva stands majestic under an overhanging tree. Sit under it and you will see ants going about their work, and bees flitting around, and hear birds sing of dawn and day in different notes. Step carelessly and you can destroy nature‘s harmony in an instant, which, unlike the Rajbari, cannot be rebuilt.

It is a world apart, this hidden space that stands a step away from the world outside. When you start back, the rush of moving people, in rickshaws and buses, cars and two-wheelers, the blaze of posters for movies and politicians, the noise of loud speakers and horns will bring you back to reality. You will know you were lucky to have got away, albeit for the blink of a moment in time. The zamindars of today are not quite so lucky.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

The Nimtita Rajbari in Murshidabad was where Satyajit Ray shot Jalshaghar, not in Bawali Rajbari. Mrinal Sen's Khandahar and Rituporno Ghoshit Chokher Bali were shot here -- the former also shot in Kalikapur Rajbari near Shantiniketan

Indrajit Hazra

Oct 20, 2021 at 01:33