Bushwick Collective, an open-air gallery, has not only transformed the neighborhood but also helped Brooklyn regain some of its lost sheen as a mecca for freethinkers, deviants and resolutely anti-establishment types. Photos: Vikram Zutshi

In a little over a decade, Bushwick in northern Brooklyn has gone from an assortment of garages, warehouses and the occasional brownstone to the heartbeat of New York’s art scene

I used to share a duplex apartment in a four-story Brooklyn walk-up with a Dominican indie rock producer and an Istanbul-born-journalist-cum-performance-artist. We rarely had a quiet night, but that’s the way we liked it. There was always a motley bunch of people lounging around the living room, drinking wine, spinning records, cooking, trying out costumes for a photo-shoot or practicing lines for a play.

Our salon could have very well been a cross-section of bohemian Brooklyn, with visitors ranging from their twenties to sixties, and hailing from Russia, France, Japan, South Korea, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Iran, Tennessee and Utah.

But the neighborhood wasn’t always this freewheeling. Brooklyn resident Joe Ficalora had barely reached his teens when his father was murdered outside a subway stop in 1991. The Bushwick neighborhood where he grew up was a hotbed of gang-related violence. Twenty years after his father’s death, his mother succumbed to a brain tumor. Joe was at his lowest point when he embarked on a mission to transform his neighborhood, hoping to start afresh and erase memories of his traumatic childhood.

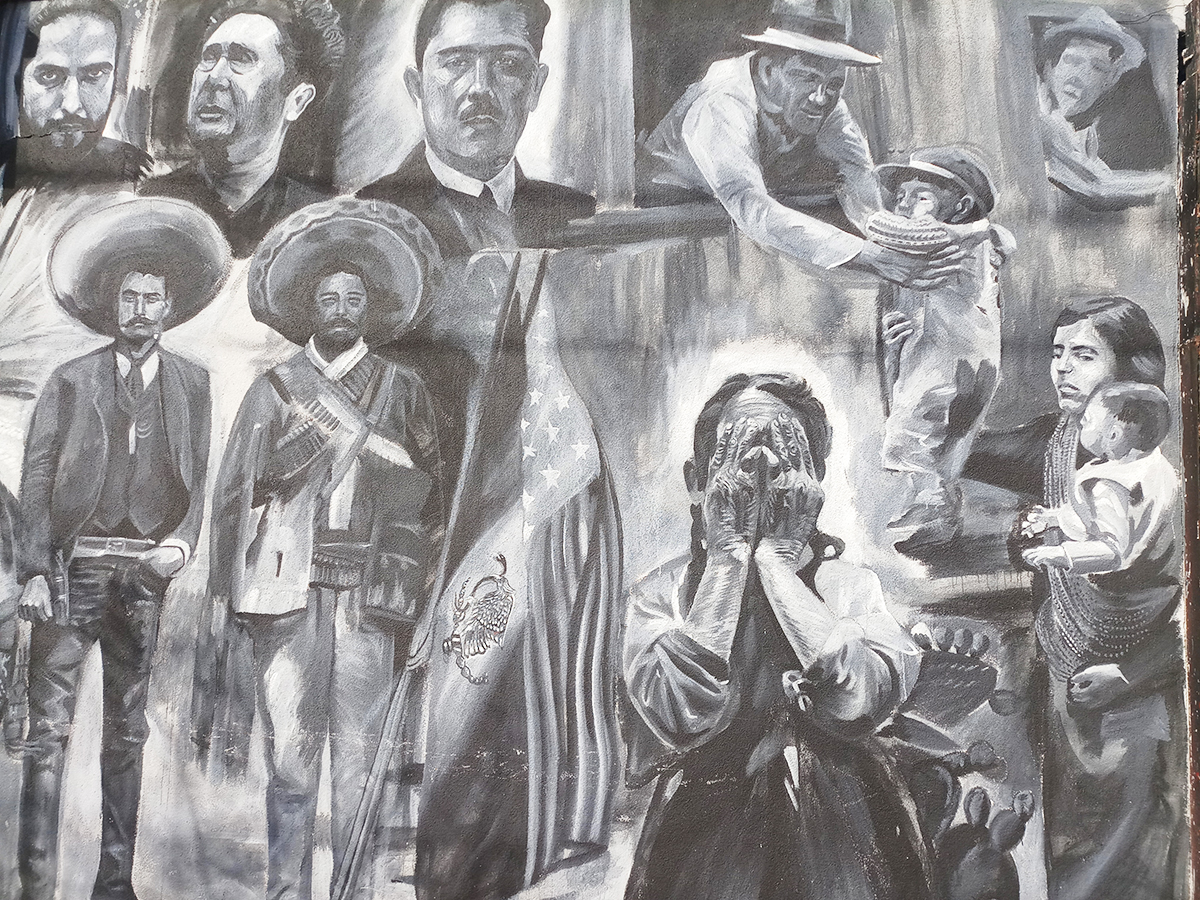

Street art in Bushwick

The resultof his efforts can be seen in the Bushwick Collective, an incredible open-air gallery that has not only transformed the neighborhood but also helped Brooklyn regain some of its lost sheen as a mecca for freethinkers, deviants and resolutely anti-establishment types.

Ficalora invites artists from around the world to decorate garages, factories and coffee shops with their colossal murals. The result? A highly visible venue for emerging artists to showcase their work and some of the most hip and eclectic streets you are likely to see anywhere.

Nychos and Lauren YS from California, Ruben Ubiera from the Dominican Republic, Rosk and Loste from Sicily, Javier Barriga from Chile, Michael Velt from the Netherlands, Shawna X and Cody James from Brooklyn are some of the better-known members of the collective. Because of the constant wear and tear, murals are refreshed every year, treating visitors and residents with a revolving selection of stunning street art.

The area still retains much of its working class flavor and Latino roots, with nearly 70 percent of residents being of Puerto Rican or Dominican origin. It feels a bit like what Berkeley and Venice beach on the west coast used to be thirty years ago and what Tribeca, SoHo and Greenwich were in the Seventies and Eighties.

The coffee shops in Bushwick, and indeed all of Brooklyn, deserve a special mention, for this is where I got most of my work done. These places are a throwback to the days when people actually read books and had conversations about art, life and politics while sipping their beverages. A collection of short stories and a screenplay I am working on were hatched at Variety, a minimally designed yet spacious coffee shop near my house.

In a little over a decade, Bushwick has gone from an assortment of garages, warehouses and the occasional brownstone to the heartbeat of New York’s art scene. Today there are over sixty galleries scattered throughout the area ranging from mainstays Clearing and Signal — two huge converted warehouses, to the Centotto Gallery, which has organized more than fifty exhibitions in the span of nine years. Interstate Projects, a nonprofit that gives artists space for large-scale works, adds to the DIY sensibility while a branch of the Chelsea gallery Luhring Augustine has also opened its doors. And every September, Bushwick Open Studios welcomes throngs of people from all over the world for a giant event where all the galleries and studios of the neighborhood are open to the public, giving artists the opportunity to introduce themselves and to display their works.

Like many others, Olivier Babin, the founder of Clearing, was initially drawn to Bushwick for the huge spaces and affordable rents it offered. He lived and worked in the same space, as others did, and provided a platform for several local artists to exhibit and sell their wares. Today, Clearing has branches on the Upper East Side as well as in Brussels, Belgium.

Every September, Bushwick Open Studios welcomes throngs of people from all over the world for a giant event where all the galleries and studios of the neighborhood are open to the public.

The vibrant scene draws lots of visitors and has revitalized the area with small businesses springing up everywhere. So you can spend the whole day taking in the best of NYC’s street art, pizza, cocktails, artisan coffee and tacos. Rest your weary feet at Wyckoff Starr, a hole-in-the-wall coffee shop, stop for delicious (and cheap) tacos at Los Hermanos and later, drop in to the House of Yes, showcasing burlesque dancers, circus acts, magicians, theater and cabaret performances, famed for its strange theme parties and the many varieties of nocturnal bacchanalia.

Punk afficionados hankering for the no-bullshit punk scene of the Seventies can go to Birdy’s Bar, founded by co-owners Holly MacGibbon and Andy Simmons (who also perform as the goth-rock duo Weeknight. And for those interested in the circus arts, Bushwick has a circus school called theMuse.

Despite the effervescence in the air, residents cannot help feeling that it is only a matter of time before Bushwick is overrun by tech bros and yuppies. Over the next few years, more new apartments will be built in Bushwick than anywhere else in the city. The rapid influx of new residents is already jacking up rents.

Making art is as ruthless a business to be in as any, especially in a place like New York, which can turn its jagged frontiers into gentrified spaces, peopled by trust-funded hipsters, in the span of a few years.

One way that new waves of young creators in New York survive is to keep expanding outwards into more affordable neighborhoods. For instance, Kathy Grayson of the gallery Hole, did a show with dozens of new artists, many of them based in Ridgewood, on the border of Brooklyn and Queens.

If you build it, they will come. Sometimes the only way to save a movement is to move out and take it with you.

(This essay was part of May 2021 issue, which was delayed due to the pandemic and released on August 3)

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated