.jpg)

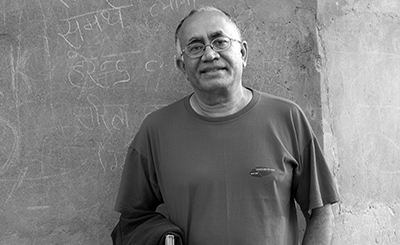

Amitava Kumar. Photo: amitavakumar.com

Amitava Kumar’s latest, The Blue Book, offers a picturesque collage of journaling, writing and consuming literature in a pandemic-ridden world. He talks about how so much of art is just an accident how he, as a writer-artist, recorded the contradictory realities of the world around him during the pandemic

Having authored several works of non-fiction and novels, Amitava Kumar’s latest, The Blue Book (HarperCollins India), offers a picturesque collage of journaling, writing and consuming literature in a pandemic-ridden world. A Guggenheim fellowship awardee, including residencies from Yaddo, MacDowell, and the Lannan Foundation, Kumar’s work has also appeared in The New York Times, Granta, Harper’s, to name a few. His novel, Immigrant Montana (Knopf), made it to notable Best of the Year lists at The New Yorker, The New York Times, and on Barack Obama’s list of favorite books of 2018. Kumar is professor of English at Vassar College in upstate New York. Excerpts from an interview:

The Blue Book is a beautiful amalgamation of writer-artist collaboration. Here, you play both the roles. How did the idea of a writer/artist journal come to you?

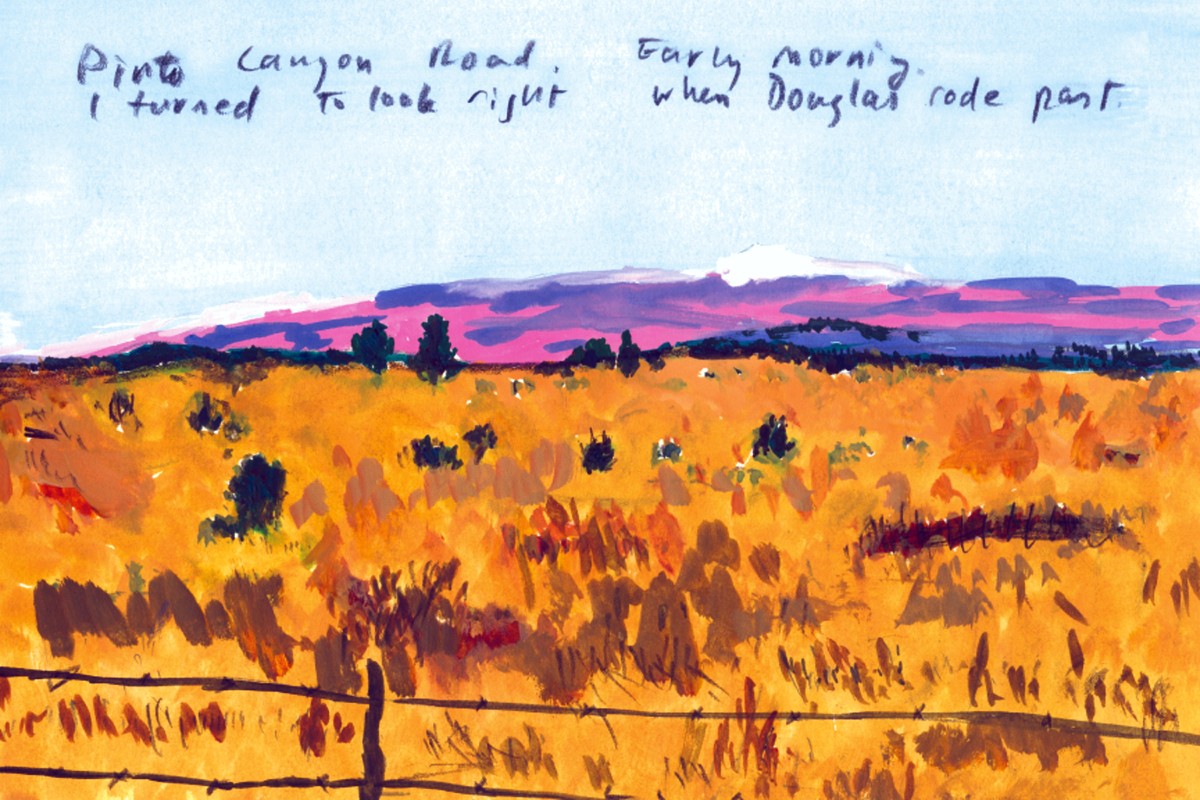

The idea for a book of drawings came from Hemali Sodhi at A Suitable Agency. During the lockdown, I was drawing every day. It was something to do with my children. When Hemali first mentioned this idea, I didn’t think much of it. But later, because I was also keeping a daily journal, I began thinking that yes, the journal entries could provide captions for the drawings. It was a sudden inspiration and made complete sense to me. So much of art is just an accident: you have to be alert and wait for it to happen.

You mention drawing as ‘a more deliberate act.’ Would you say it has changed the way you write or has helped you perceive the world differently?

Well, I also think of drawing as a kind of writing. I’ll be walking on a street and I’ll notice the way in which the roofs of houses jut into the sky and I’ll realize that my eye is drawing the outline of the buildings. When you draw, you are looking closely. You pick up a stone that looks black but when you begin to draw it you notice the tiny pink spots and maybe a little glint of silver. And, of course, good writing grows out of serious noticing.

Do your novels stem from vignettes collected and preserved in journals over a period of time? Or does the idea for a novel first appear in your mind followed by various journal entries till the story is fully formed?

Yes, the former. It certainly was the case with Immigrant, Montana and with A Time Outside This Time (Aleph Book Company). It is a method I recommend. You can be making notes, cutting out clippings from newspapers, doing some research, and one day, you will find an opening. Then begins the process of giving shape to the narrative.

The Blue Book’s beauty lies in its ability to connect writers/artists to their art and to ultimately find solace in the mundane. Was this something you actively pursued?

During the pandemic, in a world ravaged by disease and the loneliness of death, you had to look for beauty. I couldn’t get on a plane and go to Ladakh (I hear it is very beautiful—I haven’t been there) but I could go into my backyard and then step over some branches and find myself next to the creek that flows past. I could draw that. We had weeks of spring here even as reports of the second wave were coming from India. There was the death toll—but there were also tulips in the garden. In The Blue Book, I tried to faithfully record all those contradictory realities in the world.

One piece of advice you give in the book is about having “knowledge that is specific.” Could you elaborate on that?

Ab mujhe yaad nahin hai ki maine yeh baat kahan kahi hai (Now, I don’t remember where exactly I said this)… But this is what I think I was talking about. Even as we were faced with a pandemic, the WHO released a statement that we were confronting an “infodemic.” The world was suffering from the contagion of fake news. I was working on a novel that became A Time Outside This Time. So, all my energies were bent on thinking about how to escape false generalities and find real, hard, complicating truths.

Journaling is like memory-keeping. And memories, considering the times we live in, act as a tool. How important do you think it is for writers honing their craft to relentlessly journal?

You know, our gadgets like our smart-phones remember things that we forget. For example, when and where was a photograph taken. Your computer also remembers what you forget. You can check your email inbox and remember when your friend wrote to you to ask for money and how much you agreed to give. Now, these machines are helpful but they are taking over our own ability to remember. I’m startled to find how much I allow myself to forget. The other day I was reading letters I had received from a young woman I was in love with forty years ago. As I read her letters, I began to remember so much. Precious memories—and feelings—returned to me. I put things down in my journal so that everything isn’t forever lost to me.

This practice is important for writers not so much because then they will remember, though that might be true, but because it is good practice. You are always writing because life is always happening. You are filling up pages. You are never blocked.

The pandemic threw the world in a limbo and forced humans to adapt in myriad circumstances. How do you think the pandemic has changed the way readers perceive literature or consume art?

Too early to tell, I think.

I know that the pandemic, because it was global and because it was so severe, and because it is still ongoing, changed something fundamental in our lives. Has it rewired how we approach art? I don’t know. In The Blue Book, and also in A Time Outside This Time, I was trying to record the experience of living through these times. Not just living or surviving through these times but, more particularly, the search for truth and beauty during the difficult days that are still not over.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

THUMB.jpg)