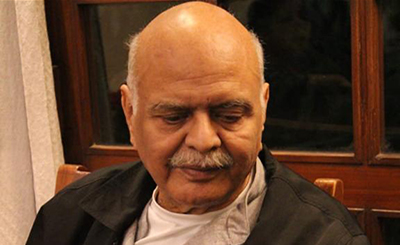

Cyrus Mistry, 60, is the author of two plays, two novels and a collection of short stories. Brother of Rohinton Mistry, he grew up in Mumbai. The author and playwright says that as a school boy, he wanted to be a musician. “I was playing the piano. I wanted to compose music in the Western classical tradition. I was (attempting) to write string quartets, pieces for piano and violin, etc. I was also actively studying subjects like Harmony and Counterpoint at the Bombay School of Music and under Joachim Buehler at the Max Mueller Bhavan. But it didn’t take me long to acknowledge to myself that I lacked the hard discipline and single-mindedness it requires to forge a true musical virtuoso,” he says.

During his first year at St. Xavier’s as a regular student, exposure to good writing and good teachers put him “squarely on course to becoming a writer”. He says, “I was already a part-time journalist, publishing articles in Debonair magazine, and selecting their monthly short story. I was, however, refused re-admission to college after my Jr. B.A. for my involvement in organising a student strike. That was, undoubtedly, a blessing in disguise. I took a break from academia, and wrote Doongaji House, which won the Sultan Padamsee Award in 1978. Incidentally, this matter of self-confidence as a writer could be viewed in the context that it’s the only thing I can, or know how to do, well.”

It took Mistry 20 years to actually write the novel whose first chapter he began in 1979, immediately after he had completed Doongaji House. It later became The Radiance of Ashes, his first novel, which was shortlisted for the Crossword Prize (2005). Mistry won the 2014 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature for Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer, his second novel, published by Aleph in 2013. The novel also received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 2015.

Mistry worked as a freelance journalist for 25 years. He has also written short film scripts and several documentaries. One of his short stories, “Percy”, was made into the Gujarati feature film Percy in 1989 — he wrote its screenplay and dialogue. It won the National Award for Best Gujarati Film in 1989 as well as the Critics’ Award at the Mannheim Film Festival.

The Radiance of Ashes is a coming-of-age story about a young man who gets politicised even as the city he lives in, Bombay (now Mumbai), gets politicised, as it were, in the early 1990s. How does a writer transmute his/her own experience into art? How does one make the intensely personal into the universal, something that unknown readers can identify with and make their own? Mistry says that he doesn’t really know how. He says, “It’s too central to the focus and turbulence of the creative process itself to be able to spell out discursively. What I will say, though, is that like the character Jingo, I too had a deeply romanticised relationship with my city which shattered into pieces in a most disturbing way during and after the riots of 1992-93. Writing the novel helped me come to terms with the fundamental changes that had swept through the city, even though I wrote the novel almost ten years after the riots.”

Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer, set in the middle of a bustling city, describes, perhaps for the first time, a totally marginalised, outcast segment of the Parsi community — the untouchable khandhias. Mistry says that in 1993, during research for a documentary film that he did for a producer who proposed the idea to a foreign TV channel, (incidentally, no film was ever made on the subject), he was told about a khandhia strike in 1941 that fizzled out almost before it could start. Twenty years later, when Mistry was thinking of a subject for his new novel, he remembered this bit of information, and it became the germ of his story, “developing later in a very different direction”.

Passion Flower (Aleph, 2014), Mistry’s first collection of short fiction, brings together seven tales of derangement. The derangement of characters plays out within the confines of family. “Families are a fertile breeding ground for every form of derangement and disorder, wouldn’t you say? Perhaps it’s something in the very nature of this social unit of organisation,” says Mistry.

The author, who now lives in Kodaikanal in Tamil Nadu, is currently working on his third novel. Set in Kerala, it doesn’t have a single Parsi character, says the author about his novel-in-progress. Excerpts from an interview:

ARSHIA SATTAR: I want to get this awards thing out of the way, so let me start with that as a question. You’ve written in so many genres — novels, short stories, screenplays and plays. Your work in each of those has not only been critically acclaimed, but individual works have won awards. And now, the Sahitya Akademi award for your entire oeuvre. What do you enjoy writing most? Which award has meant the most to you?

CYRUS MISTRY: Incidentally, the Sahitya Akademi Award was not for my entire oeuvre, but for the best novel in English of 2015, i.e., Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer. Since I haven’t written any new play in a while, you may be surprised to hear this: the genre I find most exciting to pursue is writing for the theatre. It’s a form that’s concentrated, double-distilled, as it were, and I see it as closer to lyric poetry than to prose. It also happens to be perhaps the least remunerative form of writing, which is what probably compelled me to start writing novels.

The award that meant most to me was undoubtedly the DSC prize (for South Asian Literature, 2014) primarily because of the sheer corpus of its cash component, which helped clear a backlog of outstanding debts: an enormous weight off my back. If that sounds cynical or hard-headed, believe me, it’s not. It’s simply a wonderfully tangible relief when talent is acknowledged, and financial difficulties recede.

ARSHIA SATTAR: Since we’ve had a chance to spend time together, I have been struck by your confidence, how sure you are in your writing and your work. It’s remarkable and has nothing to do with winning awards and being recognised. Where does that come from? Did you always want to be a writer? What does that mean as a young person? How does one “prepare” to be a writer? Does it have anything to do with having another acclaimed writer in the family?

CYRUS MISTRY: In fact, as a school boy, I wanted to be a musician. I was playing the piano. I wanted to compose music in the Western classical tradition. I was (attempting) to write string quartets, pieces for piano and violin, etc. I was also actively studying subjects like Harmony and Counterpoint at the Bombay School of Music and under Joachim Buehler at the Max Mueller Bhavan.

But it didn’t take me long to acknowledge to myself that I lacked the hard discipline and single-mindedness it requires to forge a true musical virtuoso.

During my very first year at St. Xavier’s as a regular student, exposure to good writing and good teachers, had already put me squarely on course to becoming a writer. I was already a part-time journalist, publishing articles in Debonair magazine, and selecting their monthly short story. I was, however, refused re-admission to college after my Jr. B.A. for my involvement in organising a student strike. That was, undoubtedly, a blessing in disguise. I took a break from academia, and wrote Doongaji House, which won the Sultan Padamsee Award in 1978. Incidentally, this matter of self-confidence as a writer could be viewed in the context that it’s the only thing I can, or know how to do, well.

At the risk of sounding niggardly, I should set the record straight on my celebrated elder brother, Rohinton. Ironically, Rohinton too had wanted to be a musician to begin with. He strummed guitar, wore a contraption round his neck designed from the family Meccano set that clamped in place a harmonica, and sang Bob Dylan, James Taylor as well as more traditional American folk songs. He was enormously popular at college functions and had even cut an E.P. record for Polydor, India, before he decided to emigrate to Canada. I still think he was a really fine singer.

When he went to Canada, he gave up the idea of finding success in the field of music and took evening classes in literature to relieve the drudgery of working at a bank during the day. It was only after he had read Doongaji House (in manuscript form) and my first short stories, published in Indian magazines, that Rohinton felt inspired to begin writing the stories that comprise his first book, Tales From Firozsha Baag (1987). The double irony is that both Rohinton and I were failed musicians to begin with, before we became relatively more successful writers.

Although I must add that the incredible fan following Rohinton’s books still have even 15 years after his last novel came out indicates there must be something quite remarkable about his work.

Cyrus Mistry with wife, Jill, and son, Rushad

ARSHIA SATTAR: A writer grows as he/she writes more and more, if nothing else, because his/her craft gets better. From Doongaji House to Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer, your milieu has remained the same, the Parsi community in Bombay. The Parsis are in all your work, for obvious and good reasons. How have you grown as a writer in 30 years? What has changed in your depiction of this community?

CYRUS MISTRY: Firstly, I can’t agree with your primary statement that the milieu in my writing has remained the same from Doongaji House to Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer. You could perhaps say that about Rohinton’s work — from Tales From Firozsha Baag to Family Matters, his entire oeuvre strictly concerns the Parsi community and is entirely based on his nostalgic memories of his past life in Mumbai. It is revealing to note that he has never written a single story that is set in Canada, where he has spent the last forty years of his life, nor even introduces a single Canadian character in any of his novels or stories. It’s all Bombay, and in the past.

I remember feeling quite strongly, after completing Doongaji House, that I had in some ways “exhausted” the extent to which I could mine the community’s sense of fragility, decay, inability to adjust to a changing world — that vulnerable, bitter-sweet pathos of existential yearning, anguish and loss that may be a central paradigm of writing about a dying community.

It took me twenty years to actually write the novel whose first chapter I began in 1979, immediately after I had completed Doongaji House. That was the novel which later became The Radiance of Ashes — anything but a “Parsi” novel, even though its main character is a sort of renegade, lapsed Parsi. It’s a novel that concerns itself with the churning of a whole society, the demolition of the Babri Masjid, the cynicism of political machinations, the savagery of Hindu-Muslim riots across the country, the transformation of the ethos of an entire city — Bombay into Mumbai — the final deadly clasp of a doddering Parsi woman, who protects her younger Muslim friend from a rioting mob which sets both women on fire within their barricaded flat.

But before I could find the wherewithal to deal with financial exigencies, and perhaps also the essential laziness that had hampered my writing of that novel, I spent 25 years earning a living as a freelance journalist. And there’s a body of work there, I suspect, waiting to be compiled, that will conclusively establish that I have never concentrated on writing only about my community in any narrow or restrictive sense.

Even Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer, a novel that describes, perhaps for the first time, a totally marginalised, outcast segment of the community, cannot strictly be called “Parsi” in the sense you mean, clubbing the community’s literature in one basket. In fact, my next novel, set in Kerala, which I’m still working on, doesn’t have a single Parsi character.

ARSHIA SATTAR: The Radiance of Ashes was your first long work, a coming-of-age story about a young man who gets politicised even as the city he lives in, Bombay, gets politicised, as it were, in the early 1990s. There are parts in it that seem very close to your own life, your own experience, your own political awakening. Your writing is very firmly rooted in what seems to be your immediate environment. How does a writer transmute his/her own experience into art? How does one make the intensely personal into the universal, something that unknown readers can identify with and make their own?

CYRUS MISTRY: It would be disingenuous, if not downright pretentious of me, to attempt to answer that question about the process of transforming the intensely personal into art. I don’t really know how — it’s too central to the focus and turbulence of the creative process itself to be able to spell out discursively.

What I will say, though, is that like the character Jingo, I too had a deeply romanticised relationship with my city which shattered into pieces in a most disturbing way during and after the riots of 1992-93. Writing the novel helped me come to terms with the fundamental changes that had swept through the city, even though I wrote the novel almost ten years after the riots.

ARSHIA SATTAR: The Radiance of Ashes has a grand narrative arc and a large canvas. Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer is like a miniature painting, even though it has so many characters. I’ve always been impressed with how full and rich your minor characters are — even if you don’t tell it, the reader feels that there is a back story for each of them and they are utterly real. How do you develop a so-called minor character? Do they ever push their way into the novel, taking up more space than you had intended for them? Do you feel that there’s a point at which your characters control their own destiny?

CYRUS MISTRY: I suppose every writer would perforce offer a distinctly, personal response to this sort of question. Myself, I can only say that I don’t believe there’s anything mystical about the process of writing, nor any autonomy a character can possibly exercise over the discerning judgment of the writer, so that “a minor character pushes his/her way to claim more space” than earlier intended. (If that does happen, it’s only because the writer decides to revise his previous intention).

This may seem like quibbling over words, but I think it’s important not to mystify the process of fiction writing with ideas like characters “controlling their own destiny”. On the other hand, the only thing about it which does verge on the mystical or meditative is the deliberate focus and discipline of daily work, which creates its own rarefied mental space in which the author’s intention, perspective and sense of the congruent acquire a self-determining, self-regulatory dynamic.

ARSHIA SATTAR: In Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer, for me, the heart of the book is Dungarwadi, the Tower of Silence. Set in the middle of a bustling city, yet so quiet, so Edenic and yes, so cruel to the people who must live there, the untouchable khandhias. And Sepideh is the blithe spirit of that place, keeping it beautiful and innocent, in a way. In the notes at the end of Chronicle…, you mention that you were attracted by the idea of a news article about a kandhia strike in the 1940s. What is the germ of the story for you — an idea, a person, a place?

CYRUS MISTRY: What I say in my afterword to the novel is that in 1993, during research for a documentary film that I did for a producer who proposed the idea to a foreign TV channel, (incidentally, no film was ever made on the subject), I was told about a khandhia strike in 1941 that fizzled out almost before it could start. Twenty years later, when I was thinking of a subject for my new novel, I remembered this bit of information, and it became the germ of my story, developing later in a very different direction.

Stories and novels can indeed grow out of the most unlikely stimuli: a person, who suggests a character, an idea which evolves into a theme, or a place that evokes a setting for the fiction.

Cyrus Mistry receiving the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature for Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer at the Jaipur Literature Festival in 2014.

ARSHIA SATTAR: I feel that Doongaji House and your other play, The Legacy of Rage, are a pair. Both are about sub-cultures and small communities that are part of the bedrock of (now long dead) cosmopolitan Bombay — the Parsis and the East Indians. Both are about families that no longer function, both have wrenching family secrets at their heart involving infidelity. Both involve property and inheritance. We talked before about your image of the crumbling house — it appears in The Radiance of Ashes as well. Whether conscious or not, the physically decaying house and the emotionally decaying family recur in your work. Can you talk about that?

CYRUS MISTRY: When I wrote Doongaji House, I remember the first thing I thought of — which set into motion a whole string of associations and ideas — was its title.

This was a time when I was very young and had begun to find the idea of living in a flat with parents, brothers and sister insufferable. I do think that as a social institution — for the children, especially — the nuclear family is one of society’s most ingeniously oppressive devices that has an intrinsic ability to engender almost spontaneous discord and decay. The crumbling house in my first play was a symbolic layering of this theme which is at the heart of the play, as also an image for the moribund Parsi community whose members occupy the building.

If I am asked to talk about this notion, I would admit: families everywhere are oppressive, and once they have served their purpose, after a child has attained maturity, can only sustain festering and decadent relationships. And families will always have secrets involving infidelities — sexual, emotional or economic.

With land-owning East Indians — original settlers of the fishing villages of Mumbai and north Konkan — the betrayals have been of a slightly different kind, engineered by successive governments of independent India, unscrupulous building contractors, ambitious go-getting relatives, and an intrinsically happy-go-lucky disposition in the community.

Although, of course, all these considerations are in the end secondary to the essential building blocks of artistic creation which have for centuries derived their source and strength, emotive power and insight from situations of social change and turmoil, degeneration, decay or loss.

ARSHIA SATTAR: You have wonderful women in your work (Cristina in The Radiance of Ashes and Sepideh in Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer), not always powerful and dominating, often broken and searching. How do you write women? Is it a difference in voice, the way they occupy the space of the novel, their relationship to power and to the world around them? I’m thinking very much of the lovely complex woman (Cristina) in The Radiance… — I’m still stunned by her. She’s unforgettable.

CYRUS MISTRY: I don’t mean to be abrupt, but the short answer to that is: like I write any other character. I think about her, about other women I have known in real life, or in fantasy, and then try to be true to the driving force of the story and the function or part she plays in the story. I do think that the rarefied focus achieved through disciplined, daily work (which I spoke of earlier) allows the writer to intuitively combine the right elements/details to create a convincing, true-to-life character, whether man or woman.

ARSHIA SATTAR: Passion Flower, your first collection of short fiction, brings together seven stories of derangement. It is essentially about people — fathers and sons, mothers and daughters —engulfed in domesticity. The derangement of characters plays out within the confines of family. Is it by design that the family is at their heart?

CYRUS MISTRY: Families are a fertile breeding ground for every form of derangement and disorder, wouldn’t you say? Perhaps it’s something in the very nature of this social unit of organisation.

ARSHIA SATTAR: What was the genesis of these stories?

CYRUS MISTRY: These stories were all written in the years while I was still working as a freelance journalist in Mumbai, and later collected in Passion Flower. That is, years before I began writing novels.

ARSHIA SATTAR: I also wonder about how we write as we get older, how much of our own fatigue and our learned wisdom seeps into our work. Chronicle…, in so many ways, is about redemption. We are forgiven, we make peace, we live in love as much as we can. Your earlier works, as a younger man, verge more towards retribution and despair in their conclusions. How does one look back on the person that one was, on the works that the younger self created? How does one absorb those works into one’s present writing self? Or, are all our works discrete? And we should not look for a self that unites them? Can/should one see one’s writing life as having its own narrative arc?

CYRUS MISTRY: For one thing, I never read what I’ve written once it’s finished and in print. Unless there is some crisis of self-confidence and I need to reassure myself. Also, my inclination and my ability to speculate about large over-arching theoretical matters, or issues of literary criticism is almost nil.

If I had to give an answer, I would think, yes, all our works are discrete. If there are thematic links and developments, that’s for critics to analyse and point them out. I feel vaguely pleased and flattered when an intelligent commentator is able to discern lines of continuity or development in my work. But my interest in such analyses does not extend beyond the first moment of listening to them. Like I said, I am pleased, and I am that because I must be doing something right for these patterns to be detected and appreciated. But it’s as if I’m in a hurry — time is running out — and I already know that this retrospective knowledge isn’t going to help me with the next book.

ARSHIA SATTAR: People are always curious about the habits of a writer — perhaps because they think that if they imitate the outer form, they’ll reach the inner content. So let’s get a sense of how your day works. Rather than asking about your “influences,” I would rather ask who you enjoy reading and why. Do you have a writing discipline — say, 6 hours every day, only at night, with a pot of green tea, one hundred mint sweets, a flyswatter ...? Other writing eccentricities?

CYRUS MISTRY: My reading habits are much too random, erratic, often frivolous and too momentary to bear discussion. Also, I have a very poor memory. Hardly anything I read stays with me for longer than a few hours, if not minutes. I hardly find time to read, except for a few minutes after watching the news on TV, and before drifting off to sleep. Isn’t that shameful?

I never seem to have the energy to be able to write for longer than two or three hours in the morning. No eccentricities, unless you club all of these together into one monstrous abnormality.

ARSHIA SATTAR: Could you share something about the novel you’re currently working on?

CYRUS MISTRY: I might have, if I could. But to summarise something that’s still incomplete is to risk rendering it seriously reductive; or worse still, of never completing it.