Photo by Kira Schwarz.

“Grief is forcing new skins on me, scraping scales from my eyes. I regret my past certainties.”

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie,

Notes on Grief

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie,

Notes on Grief

As the double mutant “Delta variant” of the coronavirus emerged in India in April 2021, I, like thousands of people, thought of my parents. In all honesty, I did not believe the virus would reach them, safely tucked away in their home in a Delhi suburb. By mid-April, social media timelines were suddenly usurped by desperate calls for oxygen, hospital beds, and virtual doctor consultation requests, and it slowly sunk in that a monstrous calamity was unfolding in India, centering around the swollen cities of Mumbai and Delhi and spreading ferociously everywhere else. Yet at that moment all this was distant.

A little after mid-April, I received a much-dreaded phone call, a dreaded moment that begot denial more than any other effect. Could it be really happening, that after a year of the pandemic, both my parents, in their seventies with underlying comorbidities, had the virus?Little did I know that the next two months would unfold like a surreal nightmare lived every second with a knot in the stomach. Even less did I understand that it would take an entire global village to save my parents: an infectious disease doctor in the Bronx, a beauty queen, the Sikh community sending aid, and people from a conflict zone, a place reviled and brutalized in India: Kashmir.

I talked with my sister, at another end of the world in Australia, both of us alarmed, wondering what to do from two different continents for our ailing parents. The situation in the first few days seemed like many other cases we had heard of: fever coming and going, cold-like symptoms, loss of smell and taste. The oxygen saturation readings at home were not bad initially. We were hopeful; frightened, but hopeful. We started organizing basic necessities during that time, namely food and medicines. A childhood friend arranged for a person nearby to deliver food to all Covid-19 patients in Noida as a non-profit service. He came twice in the first days, delivering hot food. He also texted that he was reachable anytime during the day or night if my parents were to need anything. My sister and I quickly divided the twenty-four hours between us so that one of us was always available for phone calls with my parents to check in on oxygen saturation levels, line up doctor consultations, and get help from local friends in the city. Another childhood friend I had lost contact with decades ago sent a message asking if he could help, as he lived close to my parents. The next few days quickly turned into a blur.

My day began early around 4 am with phone calls that stretched from dawn until dusk. Phone calls — numerous, incessant phone calls, phone numbers of friends, friends of friends, strangers from Twitter who had given doctor contacts, SOS groups, numbers for nurse services in Delhi. Most doctors had no empty slots, their days also wiped out by the volume of sick families trying to get online consultations. We realized soon enough that finding a doctor for a consultation was proving to be impossible, let alone finding a nurse service during the new wave of infections. The system was not just completely overloaded, it had gone past breaking point.

In the initial days, I spoke to a doctor in the Bronx who had just come out of doing covid rounds at a hospital where 20 make-shift wards had been created during the peak waves in New York. She offered long distance readings of oxygen levels and offered advice until it was no longer viable. During those first frightening days when my sister and I were unsuccessful in finding a doctor for consultation, a Kashmiri writer who I had never talked to before, serendipitously wrote to me. Her brother, a doctor in Kashmir, had been treating many Covid-19 patients and she suggested that I reach out to him. I set up a phone call for my parents, whose fever was now spiking every night. They needed treatment, tests, and medicines immediately. The doctor from Baramulla, Kashmir — hundreds of miles away from Delhi — advised that my parents go on antibiotics and steroids for the next few days and asked for tests to be done. The aforementioned childhood friend risked his own safety and visited my parents four times that week, each time bringing medication, vitamins, and whatever else was needed at the time. No monetary transactions were ever made, and he refused to accept any payment during this time.

Soon, we realized oxygen was a necessity. Already familiar with the thousands of tweets out there calling in desperation for their families to get help, pleading for oxygen cylinders, I too, became one such woman pleading and begging for oxygen so that my father could breathe. At this point, he couldn’t breathe on his own and needed a concentrator and oxygen cylinders.Another round of calls began: Twitter contacts, random names of people reported to have access to oxygen cylinders, places where they had initiated an “Oxygen langar” — a place where desperate Covid-19 patients needing oxygen but having no medical facilities could turn to. I found myself saving new contact after contact on my phone—"medicine shop Noida”, “emergency oxygen,” “Oxygen cylinder 1…2,” “Concentrator contact,” “Covid Food Service,” “Noida Kitchen Service.”A certain tweet of mine became amplified, with known Indian writers and even a Bollywood actor retweeting it to call for help. Some folks we talked to on the phone were ready to sell us oxygen cylinders or concentrators that someone locally could pick up and drop off at my parent’s home — and they named their price — a huge, hefty sum for each oxygen cylinder that in times of “normalcy” would not cost more than few hundred rupees. Oxygen concentrators were black-marketed during this time for prices that ran in the range of $3000 each. Making money had become a sport during this tragedy.

That night, after a day spent searching for oxygen, someone from an unknown source rang the doorbell and dropped off an oxygen cylinder for my father that he desperately needed. I still don’t know who it was that made it possible. At the same time, I had also turned to an old friend who was abreast of the situation with my parents. She and her husband, with contacts in the Indian media, made it possible for the non-profit organization, Khalsa Aid India, to drive an oxygen concentrator overnight from Chandigarh to Delhi for my father. An act that today, as I look back, perhaps saved my father’s life.

The doctor from Baramulla, Kashmir, called every day, several times per day, checking in on my parents’ oxygen readings, making sure they had done breathing exercises, and that both were “proning” to attain maximum oxygen in lungs. Additional antibiotics, pulmonary medicines, and a required chest scan were prescribed by the doctor. Medicine shops were overwhelmed, and prescription medications had run out in the city as everyone was looking for the same medications. A frantic search for medications on Twitter led me to a stranger, a kind woman in California who reached out to me after she saw one of my desperate tweets. Her brother in Delhi knew a medicine shop where a specific steroid could be found. She asked her brother to buy the medicine and send a local person to deliver it to my parents. In time, I learned their father had also become sick, and his situation turned critical. Later I learned, as both brother and sister had coordinated to help my parents, their father had passed away in a Delhi hospital.

I often found myself staring at a wall, not making sense of the date, time, or what was happening around me. This was not panic; it was a prevailing helplessness in life’s every moment of existence.

The next massive ordeal was obtaining a chest scan. Going to a radiology lab or clinic to get a scan was unimaginable, and it was also risky for others to be exposed to my father, now confirmed Covid-19 positive. My sister in Melbourne obtained the contact information of an ambulance service that drives patients to the chest scan center. Numerous phone calls later, she announced to me that someone was found who would drive our father to the radiology clinic and back. A fleeting sense of relief was erased quickly with the realization that ambulances in Delhi did not possess sufficient oxygen mechanisms because an oxygen crisis had overtaken the city. The entire country was choking; people slowly asphyxiating to death. The driver could not guarantee that his ambulance would arrive with oxygen.The same day we had read the news that India’s most prominent journalist Barkha Dutt’s father, also sick from Covid-19, had died because he could not find an ambulance with oxygen. Another desperate round of phone calls ensued; this time paired with a race against time. Shortly, the same driver called my sister back in Australia — he had found oxygen cylinders and was able to drive our father to get a chest scan.

The scan revealed acute bilateral lung damage with Covid-19 pneumonia. Looking at the scan, our Kashmiri doctor friend, whom by now we had started calling “bhai” (brother), said, “it’s time to transfer him to a hospital.” We started contacting political leaders, more strangers, emergency ICU services, and hospitals. The entirety of the Delhi region was overwhelmed, with hospitals crammed and the number of dead increasing by the hour. Many of the deceased were not even able to receive their proper last rites with large collective cremations happening throughout the city.

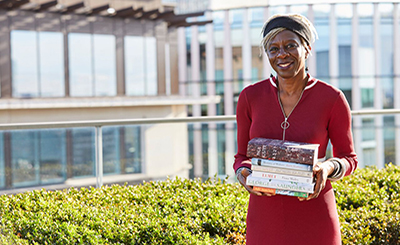

A beauty pageant winner in Noida called; she had heard that we needed a hospital ICU bed for my father. She also began calling every hospital on the city’s list on our behalf. Our doctor “brother” from Kashmir made calls too, to many of his doctor friends in the Delhi area, and one doctor in Faridabad said he could arrange something in the hospital where he worked. It was far away, but the only option. The same ambulance driver who had helped before, came again, and this was the day my father entered the ICU, now with Covid-19 pneumonia eating away at his lungs. As he left home to board the ambulance, frail and in a state of blur, my mother said to him, “You are going to the hospital to return to us in a better state.” He didn’t respond.

As I look back, the next few days were hazy but the only object I have a heightened memory of was the window I sat at all day, looking at the phone. The doctor from Kashmir took over completely, talking to all ICU doctors while still making sure both of us sisters were kept abreast of things. Incredibly kind ICU doctors took our calls at night, India time, telling us how our father was doing. Sometimes, the attending doctor of the hospital in Faridabad would connect with us on his phone and give a live video update. My father was not registering much, saying only that he wanted to go home. The first few days in the ICU, I came to know the woman working at the reception. She would always give us information about our father. “He is okay, don’t worry, we are doing everything we can, Ma’am,” she would say. Then came hiccups in the form of the hospital cafeteria shutting down for a few days and now we needed to get food services arranged for father.

My sister miraculously made contact with a nearby teashop, and a kind man named Narayan assured us that morning and evening tea would be delivered to our father, and he could even make breakfast for diabetic patients. Another friend in Srinagar, Kashmir offered to help and sent whatever food my father wanted in those days. Some days he asked for fish or chicken, and each time this friend ordered food online from Kashmir to Faridabad. He refused to talk about any monetary compensation. “Not a time to talk about this,” he said. He has refused to talk about money till this day.

On some days, father called from the hospital saying there had been sounds of loud wailing in the next room. Perhaps someone’s family member had died. He said he did not want to be there anymore. Another day, he called to say that his room’s oxygen line was taken away briefly when a nurse stated that another Covid-19 patient needed it critically. My father gave his oxygen line to him for a brief time, hoping his own lungs would carry him through. I sat with a choking feeling of “what if,” but secretly also hiding a tiny fragment of hope that if he had shared his own oxygen with another patient, it was perhaps a sign of something. I quickly suppressed the feeling, with fear, lest I jinx anything.

During that time, a helpless feeling of guilt clawed within my sister and me. Mother was alone at home, also a Covid patient. Every time when asked how she was, she would quietly say, “I am okay.” Then came the axing judgement of many who couldn’t understand why we were not able to take phone calls giving answers to: “how are your parents,” “give us an update,” “what is the news now.” Relatives called and wanted us to bring them up to speed on my parent’s health. I couldn’t muster up the courage to pick up the phone and say a word — there was nothing to say, good or bad. We just went through the days, on repetitive stasis. Then there were other voices that reminded us of our privileged existences far away, while parents were suffering alone. “What are you doing there?” some asked, not so indirectly.

One morning I heard my father was going to be transferred from the ICU to a private room. It didn’t sound real. I was surprised at my own stoic reaction. Pain had become a habit. The doctors alerted us that they wanted us to keep a lookout for Remdesivir, a coveted drug, which was supposed to heal Covid-19 in acute cases. People were hoarding the drug; it was in short supply, with one Remdesivir injection that in “normal” times cost around 900 rupees ($12 approximately), being sold by crafty people at twenty-five thousand rupees (around $340). But there was also no Remdesivir to be bought — medicine shops did not have it, and my sister and I tried to steer away from the black market. We called cousins in Singapore who had medical contacts in Delhi, who tried hard to help procure the drug. We rang a family friend living in Haridwar (four hours away from Delhi), who works in the pharmaceutical industry and asked if he could help. He sent a driver with Remdesivir injections for a week for my father from another city.

Things unfolded, as might be evident by now, in an inexplicable way.

My father was getting better but an ominous dance of death was still around us. The list of Covid deaths was getting longer: my parent’s next-door neighbor, a forty-year-old man, who had two small children; a family friend, we called “Aunty” died somewhere in a faraway Delhi hospital, her husband fighting Covid on a ventilator for weeks, followed soon after; the brother and sister duo who had initially helped find medicines for my parents, lost their father, a professor in Aligarh Muslim University. Cases kept mounting. A journalist friend who called everyday for support was now sick with the virus. My childhood friend who sent medicines four times in the first week, also caught the virus. His voice calm on the phone, he said he would beat it. One night, another friend from Calcutta called past midnight, her voice trembling — “Ma has left us” she said. She was calling from the crematorium grounds after saying goodbye to her mother.

Every phone call, every news item, everywhere one looked, someone had died, or an ailing person was looking for oxygen or a hospital bed. The horror was relentless, and yet my parents had miraculously made it. Nothing made sense. Who continued to live, and who passed away? Our doctor-brother from Kashmir told us that my father was ready to be discharged. He was weeping on the phone. He and his family video-called from Kashmir, cheering the recovery of my parents. A unique bond had connected us forever.

I write this, two months after the whole ordeal had begun. My parents are back home recuperating amidst a new lockdown. Sometimes when I call, I hear the television in the background, my mother in the kitchen with the sounds of utensils clanking, and my father humming some old song in his room. An indescribable joy in the banality. My parents are slowly recovering. They are Covid-19 survivors only because of a wave of compassion from each and every known and unknown person who made it possible for them to live. This has been a devastating time of collapse, yet also a stark reminder that our survival is acutely interweaved and connected with one another. A humanity surged and engulfed each of us in a way that leaves no words to portray it.

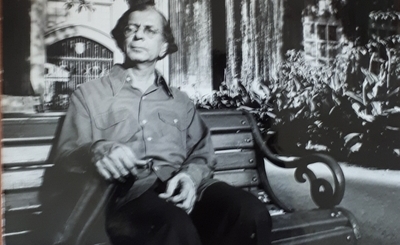

Two things are indelible in the mnemonic blur of the last two months. First, when my mother struggled to administer the oxygen concentrator to my father for him to draw air, and hundreds of miles away a doctor in Kashmir was showing her what to do, his mother, almost the same age as mine, wept in helplessness watching my mother struggle with the machine. Second, a month later, when all of us in two families across continents had met in a video call, a little girl, seven years of age, smiled brightly from Kashmir on the screen; she said, “I am a butterfly.”

Perhaps we all are, transforming for the first time.

(Our operations were affected due to the pandemic. This essay, written after the second wave of the pandemic in India, was part of our April issue, which was released in July)

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated