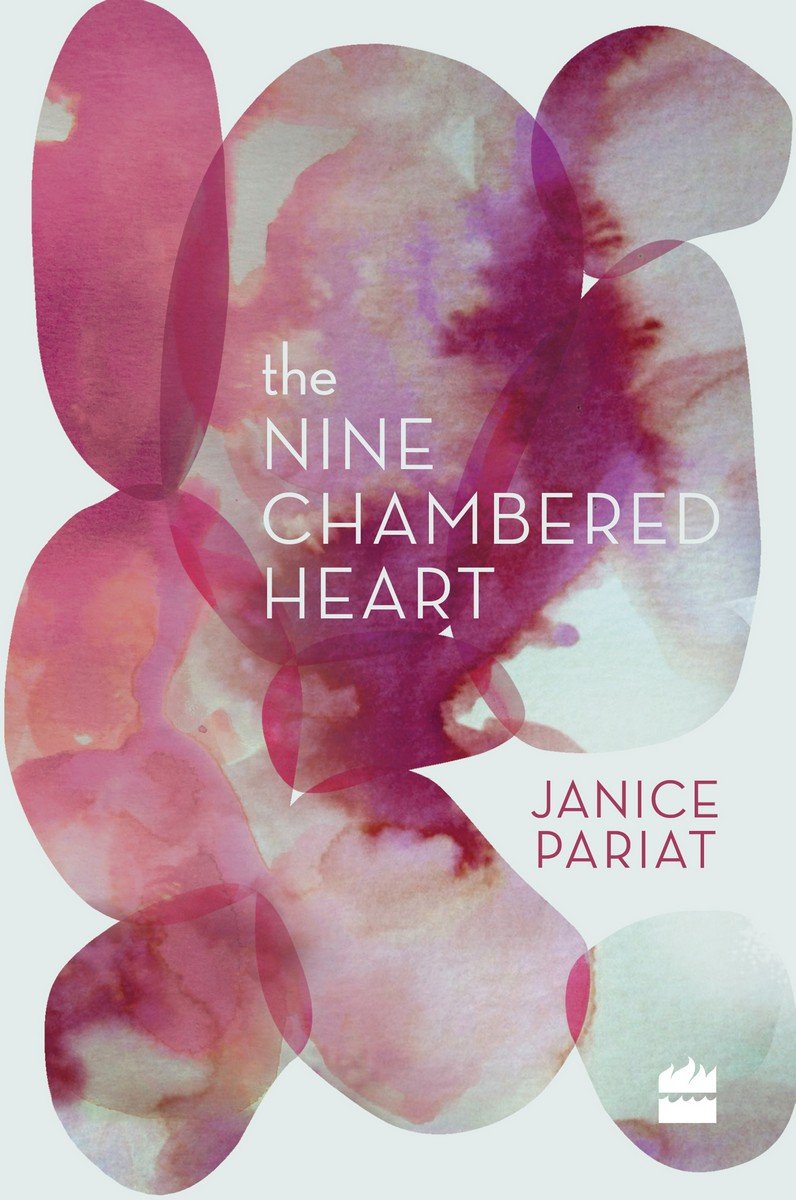

Touch, in Janice Pariat’s works , is the trail to love. In Saikat Majumdar’s novels, it is love. Pariat’s loves are successive; Majumdar’s are not so much promiscuous, with that label’s judgmentalism, as generous, joyful, all-loving

As a democratic nation, India has had some limited progress in protecting gay rights. How its massively differentiated and traditional society has adopted and tolerated this moral enjoinder is another matter. Certainly, acceptance is as important as legal recognition. But how are the politics faring at the individual level? One of the best media for feeling a nation’s political pulse is not internet or television but literature. Two current Indian authors exemplify how, at the personal level, some sexual politicking has already succeeded, in some social realms, by almost disappearing from the narrative.

These authors, Saikat Majumdar and Janice Pariat, have reached beyond self-conscious gender identification into a more deeply human world. They are enough beyond LGBT politicking, some may say they are privileged thanks to the hardworking shoulders of politicizing giants. But maybe, I suggest, such is the point of the giants’ labor.

Politics and Literature

The underlying debate is not new: Before complete revolution, should you wallow the modest laurels won or keep up the identity fight in literature and art? Should the personal still fight and politicize?

Literary response to landmark political developments can be explosive and rich, sometimes merely crumbling and weary after long struggle. Think of the explosion of the arts in revolutionary Russia. Similarly came the volcanic rise of exciting new prose and poetry in the late Soviet era in Eastern Europe, including Milan Kundera and George Konrad. Yet after the Iron Curtain’s fall, the exciting voices seemed to calm and take a nap. There was the South American literary upheaval of the 1960s up to the 1980s and beyond, with dozens of moving, ingenious works and authors. Certainly, political tremors rippled throughout that continent upon hopes the numerous autocracies starving the nations would topple. Although political advances have been made there, much remains. But the literary eruption has spent much of its lava (not to deny that fine work continues to appear).

The highly exploratory literature and cinema of post-World War II Western Europe was traceable to both exhilaration of getting past that catastrophe and reformulating a new organization of the subcontinent.

The current strengthening rise of Indian queer literature comes trapped in another political earthquake that of the religion riots in cities and in states such as Kashmir. Both major political upheavals are interrelated. They both have roots in the troubling, racially differentiated society that sincere democracy has a hard time cracking.

Solid works and authors have appeared, from R. Raj Rao and Farzana Doctor, to Devdutt Pattanaik and Anita Nair, among dozens of others. Much Indian queer lit, like that in other parts of the world, is concerned with how central characters, usually gay, differentiate themselves from others. But must a work be so steeped in a consciously differentiating identity, in order to qualify for a member of the genre? I wonder whether this differentiating outlook must hold. If not, then queer lit itself need not differentiate itself from the wider range of literature. Otherwise, it may undermine its own status of being differentiated. In turn, it may compromise the openness that the political movement demands of society at large. Inclusiveness or exclusiveness — what’s at work? Which is desired? Let’s not rush headlong.

The Theater of the All-Too-Deep Pleasure of Human Touch

I look at just a few very contemporary Indian works that exemplify not an identity-timidity but subtlety and recalcitrance in their handling of differentiation. Differentiation comes off as hardly an issue. There is no question of coming out in these works, as there is nothing given to come from or go to but only to remain as is, undifferentiated. Some readers may find such a tack a political insult.

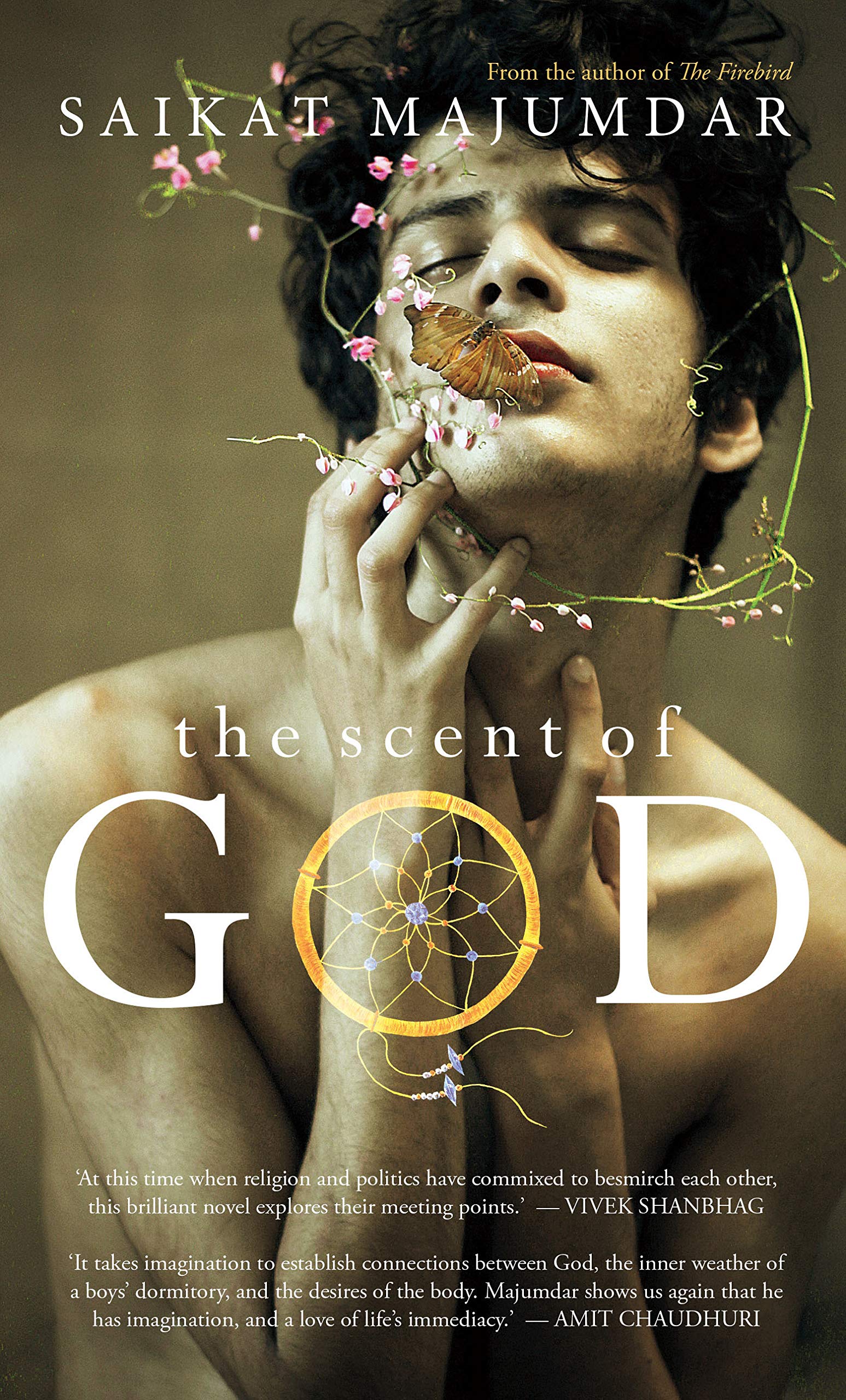

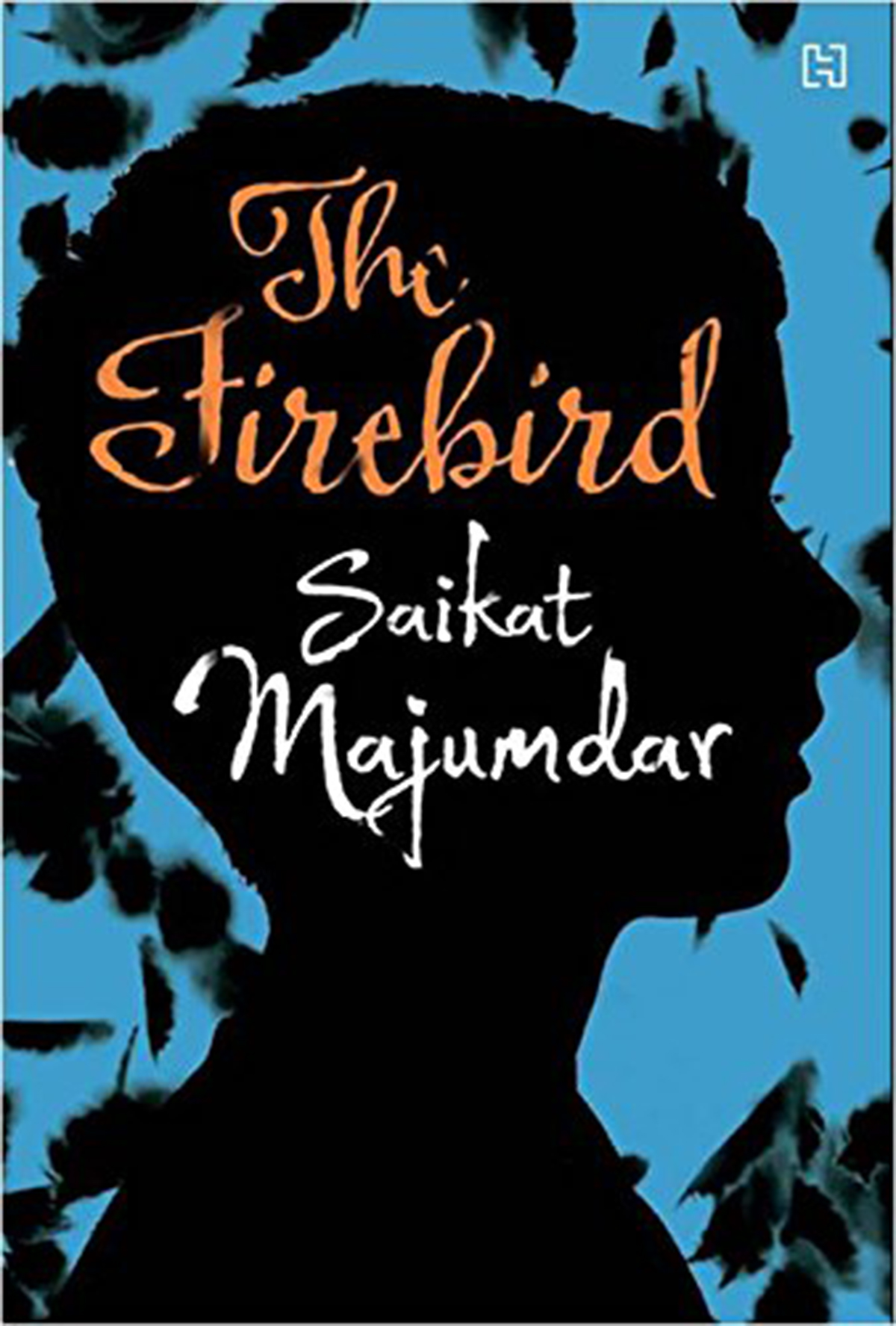

The earliest of these novels is Saikat Majumdar’s The Firebird (2013). It tells of the theater life via a close-third-person narrative following the pubescent Ori. His father is a bon-vivant and mother an increasingly desperate actress. A steady intruder and nuisance in the theaters, Ori spends much time where she plays.

The theater world is renowned for being highly sensuous, probably necessary to sustain its particular kind of social art. Not mere sexuality but all the senses buzz and scintillate in the theater. Thusly must the stage scintillate: to conjure the brilliant human world into the proscenium’s shadowy lit-up interior and nullify the audience’s stubborn incredulity. Although the senses of sight and sound are ever-abundant, the ever-present tongue and its buds deliver taste. The slithering and ever-shifting bodies and poses reek of touch, spreading like a current through the atmosphere. Even odor is sprinkled throughout, via the sneers and ecstasies of the characters.

Sensuality, as all the hard moralists of history, thumping their gavels, warn in trepidation, is the gateway to hell. And the life of the theater, as Ori witnesses without moral comment, is a fiery hell of its own.

Indeed, this Calcutta theater scene, like his mother’s life, goes up in flames — without the narration’s least judgment of it. The tale is reportage, not condemnation. It tells of a world that tells about us in our world that we think is the world. The story is of a higher-level parallel universe contiguous with the theater’s on one hand and this tangible universe on the other.

Yet, this thespian universe, sensual backstage and suggestive on the boards, is not expressly non-heteronormative. Permeating through the sheer scrim is what may be the most powerful of our senses, when it comes to forming and understanding the human being: touch. How so human? Consider what humans are: mammals. Most mammals bear their offspring internally and provide milk to the newborn — who must have this juice. They, thereby, share a cuddly proximity with one another special to their taxonomic class. Even powerfully social-insect species appear not to emphasize cuddling and hugging. (Some birds cuddle, notably penguins and parrots.) Hence cats’ loving to rub, dogs to lick your face. Mammal fur and its deeply nerve-sensitive roots accentuate cuddle pleasure. Humans are among the most hairless of land mammals. But their skin retains the sensitivity heightened by the sparsity of the heavy fur, which blocks as well as stimulates. While most mammals hug their young for weeks or months, humans do so for years.

Humans transfer this continually needed experience to select peers. As journalist Valerie Lahoux reports in the magazine Telerama (issue number 3673, 02.06.20, p.18): “The sense of touch is essential for our wellbeing,” There is an entire research institute devoted to it, the Touch Research Institute in Miami, founded by Tiffany Field, with over 400 studies conducted. Good-quality touch even helps reinforce the immune system.

The theater, in its sensuous quest, only accentuates this deeply human need.

The Firebird reveals this facet of sensuality through innuendo, hardly bringing attention to itself. Hence Ori’s longing just to touch the ticket-taker:

Staring at her, he realized why the workmen were always trying to touch her. She had firmly etched features and a skin with a dark angry glow.

He touched her face. She was real. Her skin was soft and rough at the same time… She was perfect.

She was Lila. (46)

The synesthesia only highlights the role of touch. Ori’s sensuality of touch easily translates — to the innocence of the sensed as well — to home:

Before going to bed, Ori combed and brushed his grandmother’s hair. Every night. He loved to play with the grey white strands. (50)

The synesthesia can mount and amplify and inter-define to the point that Ori seems touched in the head, like the reader touched in the heart. The synesthetic touch defines the actor and character as much as the species.

The Sandesh were delicious, and as he chewed on each piece and felt them melt in his mouth, he suffered pain, the pain of glorious taste enjoyed not in the shadow of his home, but in the yellow heat of the streets, listening to the rickshaw-pullers cry out to clear their way. (35)

All the major senses boil out from the pot of feeling, freed from the shame at home that keeps the senses from exploding, as they can in the world beyond it.

But touch reigns in this limelight world. And it does not ever lose sight of its mammalian erotic interweaving. The theater world has indeed sloughed from its oily back the wider society’s rulings and yearnings to rigidify touch. Touch cannot be caged, even in solitary confinement. That outer world cannot grasp theater’s reflecting universe. In the theater, personal identity dissolves in the synesthetic turbulence, washing away feeble gender, even age differences. It extrudes a basic human substance. All that matters is these basic human substances, even if the individuals do not quite consciously assimilate the situation.

At ten, he [Ori]] was deeply ashamed of his growing body; he would not sleep shirtless during the hours of night. He stepped back a little, away from the man. The man came closer, reached out to touch the collar of his shirt. ‘I’m older than your father. You can’t be shy with me.’

He stood limp, letting the man’s fingers unbutton his shirt. His ears felt warm and his brain clouded with the intense fragrance of spiced betel leaves. He would not fight a man who wanted him for the stage, He let the man remove all the buttons. even stretched his arms so that the shirt could be eased off his body.

‘Very nice complexion.’ The man looked pleased. ‘It will glow in the spotlight.’ (8)

And nothing more happens. No Harvey Weinstein moment. Ori here aspires to the stage, but he never sells a rupee of himself. Any violation is not a legal one, just Ori dealing with his early-adolescent shame. There is no question of heteronormative or non-heteronormative. There is simply touch of two souls willing in their ageless way.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated