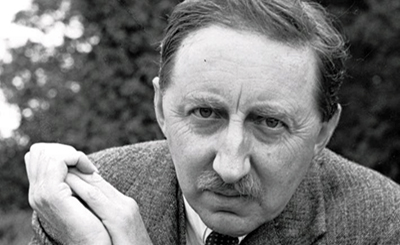

Sampurna Chattarji. Photo courtesy of the poet

Poet’s Note: Composing from an awareness of lived reality and embedded/embodied memory

It’s been a long road since 2007 when my first poetry book Sight May Strike You Blind was published by the Sahitya Akademi. Looking back, I am tempted to quote from a poem in which I invoke Amelia Earhart who, being “neither reckless not complacent” knew exactly “when to lighten the load and burden the heart”. I think that might very well sum up where I am today. As a poet preoccupied with sight and seeing, I have moved from a desire to uncover the secret kernel of things through a variety of distancing techniques to an acknowledgment that the secret self is invariably unmasked in the process of writing every poem.

If masquerade was a favoured stance in my second book Absent Muses (Poetrywala, 2010), in Space Gulliver: Chronicles of an Alien (HarperCollins, 2020), my poetic alter-ego is a robust and unabashed stand-in for the ‘I’ I had wishfully wanted to shut out. In terms of formal pursuit, Space Gulliver has been my freest form of play. Conceived as a sequence of poems — written while in residence at the University of Kent in Canterbury — I created a triangulation of forms: the dense prose of journal entries, the narrow steepled form of what I called my ‘Cathedral’ poems, and the free-ranging romp of the Space Gulliver poems. Spatially and architecturally, I am increasingly interested in composing from an awareness of lived reality and embedded/embodied memory. Among my current preoccupations are the hybrid text, the long poem, the poem as essayistic foray. This last year has seen me write to and of the moment, while realizing that some poems written years ago (on isolation, for example) sound as if they were sprung from this last year, the year of perfect vision, the ironical 2020 of a dark and terrible time.

Writing isn’t Everything

Unless you make it everything. Light

of day and stupefaction. Violation and

virus, arson and madness. Everything will not

fit. Even on a table a little larger than the entire

universe there will be things outside the “everything”

you wish writing to be. Give up. Ride a bus to work and

back. Notice women’s fingernails, bitten tongues,

the calluses over hearts. Count the number of

casualties, daily. Remember, endlessly, all the men

you almost loved. List the first lines of all the books

you know you will not write. Half your life is over.

If you admit now — how can you — that writing

isn’t everything, what’s the other half for?

Look at the flamingos a friend offers the “troubled

world”. Feel the useless euphoria that will last

only an instant. Read The Play of Dolls. Writing

isn’t everything. Even Borges said so. I want to sit

in a ruined café with sunshades on. I want to remember

the words on the casks at the Old Battery Wharf. I want

to be the picnicker with a book in the garden

of Mughal tombs. I want not to give up. I must answer

to the demands of the day. I must be answerable.

I must not repine. If writing isn’t everything, what is?

Catkins and ladybugs and let the summer come.

Dry stalks will fall and all the littered parks wonder

where all the folk have gone. And one day, it will be

habit, uniform as nun’s attire, armour against

enticement, and I shall miss the stormy weather,

the flash floods, and the squalls. Until then, can I not

admit the ancient faults? Over aware of weight, I slump

into the earth’s hard time. The text of heaviness.

How to leaven the leviathan, open the levee, levy

the norm? There is no leeway for the lesser known,

larking after a latitude given to no other. Let it bleed.

Lycanthropic sum of all heavens lost. Leave it be.

From dominion to wilderness, and back. In the end,

even the body relents. Everything,

for the other half

that isn’t.

(previously unpublished)

The Surprise is in the Slowness

Inside the juddering sound of machines forever on, the turn

away. What is the source of energy? Or do I mean, is there

a source other than energy? Tap the root. The square root

that will raise the power, the effective co-efficient as a

booster in a plant. How could ‘plant’ hold two such contra-

dictions? Flowering shrub of industry. Manufacture of living

organism. I must be both. Synthesize the sun into energy-

nutrient. Be the site of making. An industrious plant, rooted

in unmechanized soil, turning like the clock through the days,

absorbing the brilliance of noon. Process the givens into sap.

The juice that runs the systems. Why, then, also weakens?

Energy worn away by Systems Applications & Products.

A goof. There is no watery solution to this problem.

How to use sap has not been adequately explained.

Blunt object. Extension of a trench. Fortification is food.

Right now — in the eroding light — I choose sapling, more than

seed, less than tree, fourteen centuries old.

(previously unpublished)

Monsters May Do What Men May Not

Monsters may do what men may not. In your country

what is a monster? In mine, there are many demons, some

hideous, but none beastly, none monstrous in the way you

mean, just god becoming man becoming beast becoming

god. Overnight a hole appears in the wall, as if Narasimha

has climbed out of her story earlier that evening and not

finding a pillar to break out of chosen instead a plain white

plaster wall next to the lift and the fire extinguisher. Who

among the roistering lads did he come to save from a

monstrous father? Which of them in hoods and sneakers

was glad to be delivered from rex tyrannicus, demon-king,

doer of terrible penances, capable of standing on one foot

for millennia, shaming the son who has a religious streak,

turned vegan, reads poetry? Poetry is not plastic surgery,

said the poet in her hometown, before she left. The limits

of individual plasticity, said the lecturer in the seminar

room, after she arrived. Is there a point beyond which the

individual hardens into the concrete unchangeable? Is that

you, age four and you, age fourteen and you, age forty-one?

You’ve changed, but it’s you all right. The only god is

writing, the poet wrote in her book, before she left. Yes,

but what of the god in disguise, the god who assumes half-human

half-animal form to tear out the guts of a father

before his only son’s eyes? Feed him gratitude, stupor him

into drinking, slowly, the milk meant for a newborn calf.

Marked with a Blue Cross the Sofa the Mug the Radio

Marked with a blue cross the sofa the mug the radio the

window items on sale the reflection in the window the legs

on the sofa the lips on the mug the voice on the radio

marked with a blue cross more fun less money dressed as a

Spanish lady with my fan and a flower in my hair price

includes parts labour and safety checks your local blood

bank is running low self-esteem running low her hair so

glossy even in this resolution her cheek so taut her sari so

resplendent leaning forward this is perfection and when

you talk like that the men go mad redemption is not seeing

images of others intact in their beauty thirty-five thousand

pounds a number worth hanging on to as the blue cross

travels marking chocolate truffles frying pans finding a way

in the dark wrists weak with wringing a name like

Hummerstone may be worth adopting if only to inscribe

on a small white card a small blue cross that is the opposite

of ‘I understand everything’ isolation like a hair-shirt worn

willingly the abject d’art

(From Space Gulliver: Chronicles of an Alien, HarperCollins, 2020)

The essay and the poems are part of our Poetry Special Issue (January 2021), curated by Shireen Quadri and Nawaid Anjum. © The Punch Magazine. No part of this essay or the new poems exclusively featured here should be reproduced anywhere without the prior permission of The Punch Magazine.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated