'Shadow City — A Life After’ by Sudarshan Shetty. The skeletal structure is produced with local craftsmen who make objects for various religious and social ceremonies.

Bhubaneswar Art Trail achieves what it had set out to do, quite impressively and in the process, brings together a community of people from the city and far beyond.

The responsibility of a curator becomes even more challenging if it involves engagement with the indomitable cultural heritage of a medieval town whose history dates way back in time.

This was what struck us when we went meandering down the Bhubaneswar Art Trail (BAT) recently, exploring the installations of 20 artists, whose art practices have been truly immersive experiences, as they lived and worked in Odisha for months, creating their individual art projects with mediums varying from thread/textile, clay lamps and stainless steel.

Instead of balking at the prospect of installing art works where few art spaces existed, Jagannath Panda and Premjish Achari have brilliantly transformed the nooks and crannies of this ancient town into sites that lend themselves to the task on hand quite seamlessly.

If Venice, Kassel or Muenster have grand palaces and museums, in Bhubaneswar, temple complexes are used, the terracotta walls are crumbling with age but deities preside in their little niches, the faithful still come at dawn and dusk to light lamps and place flowers at their feet.

At the Shiva Temple on the banks of Bindu Sagar, the exquisite sculptures outside on the walls are luminous in the light of the full moon. The day’s prayers are over but the pujari stands chatting with Panda; they talk about the art animatedly. Other bystanders join and Panda is soon lost in conversation, explaining what the project is about.

By the time we leave, the group is making plans to visit the other sites. As the shadows lengthen, artificial lights throw into relief the rows of images displayed on the walls.

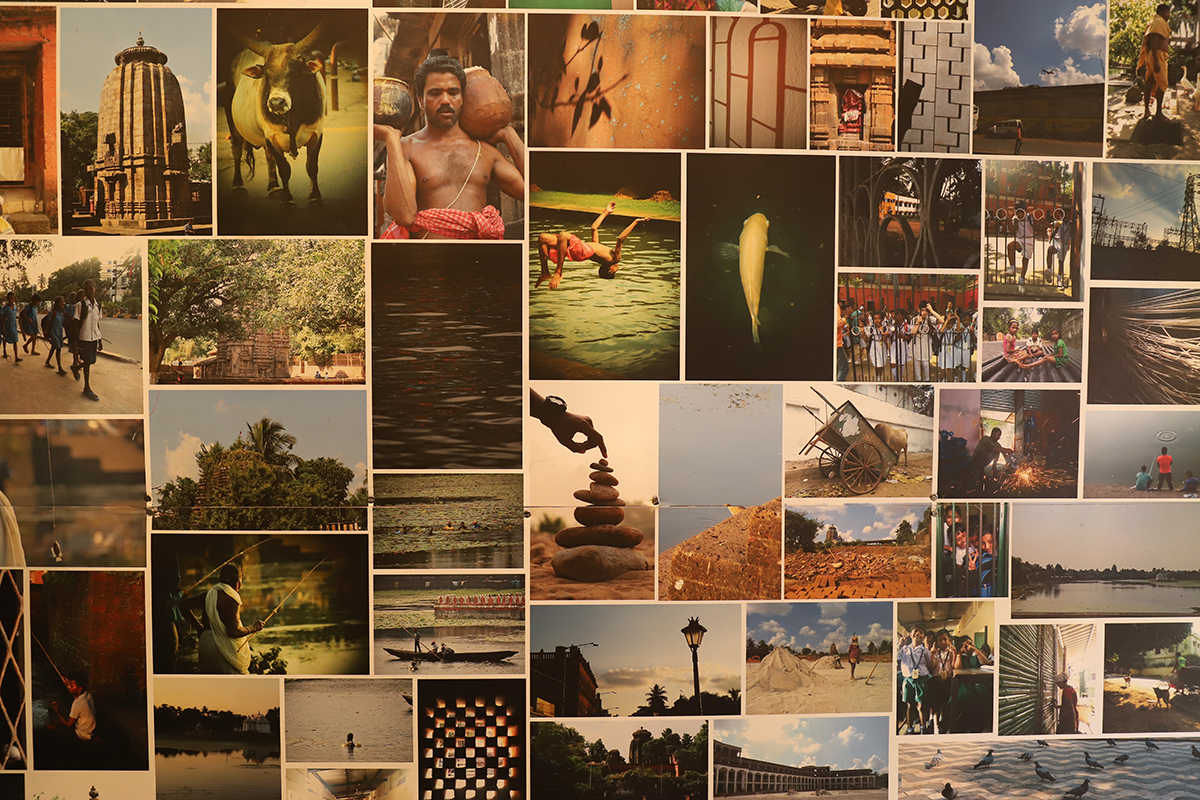

Subrat Kumar Behera’s ‘On Cultures Through Collecting’ draws inspiration from mythological and religious texts, from folklore and day-to-day news stories

Subrat Kumar Behera’s ‘On Cultures Through Collecting’ draws inspiration from mythological and religious texts, from folklore and day-to-day news stories. The artist is an accumulator of oral histories seen, heard or read.

What stood out in these stories was the idea of how any culture, people or object, is conceived in the context of its life cycle. Onlookers pass by and, irrespective of the artist’s objective, looks entranced at both the installation and the deity in a little sheltered niche, lit by a solitary lamp. It is curious and interesting to see how wonderfully the curators have used ancient sites to show works that engage with contemporary, modern-day concerns. We observe how the past and present overlap, throughout the trail, their distinctly diverse voices never dissonant or acrimonious.

Teja Gavankar’s 'Parivartan' talks about the transformation that is changing the fabric of Bhubaneswar

Titled ‘Parivartan’, Teja Gavankar’s work talks about the transformation that is changing the fabric of Bhubaneswar, the erstwhile Temple Town that is now a Smart City. He says: ‘Everything is in a state of flux, change is the only constant.’

Representing another perspective, Niroj Satpathy’s ‘Question Machine’ offers a different point of view. The artist says, “We are all aware of environmental and infrastructural crisis in the places we live, but until we self-realise and take responsibility and agency within our own environment, what change can be actualised? My work holds a mirror to the viewer, urging them to look within and discover their individual agency for change, because the personal is never disconnected from the political.”

The schism from where the many concerns and perspectives are addressed is what lends the BAT project its scale and diversity. The old town with its scattered temples dating back to the seventh century is used with great imagination and curatorial vision as a sprawling venue that showcases art installations that span a range of practices, engagements and media. It is especially wonderful to have the curators walk us through the different sites through the day into late evening.

Niroj Satpathy’s ‘Question Machine’ delves into the environmental and infrastructural crisis in the places we live

Premjish Achari meets us as we arrive and we see how magically Guajhara has been transformed with bamboo and colourful thread screens that welcome visitors to the space within. Enthusiastic volunteers are present everywhere, to explain or share details about the work or the artist. In a room on the first floor in this complex, we see arresting textile installations of Pankaja Sethi, displayed at angles, catching occasionally an elusive ray of the sun.

A young art practitioner and champion of handloom, Sethi is based in Bhubaneswar and is committed to the revival of local textiles that are gradually disappearing. We chat at her studio later, and she says: “My body of work reflects impressions of time and nature, an abstract representation of natural process integrating the landscape of the Old Town visible and fading through woven and non-woven threads. That is how I see the process, weaving stories from form to formlessness, from permanence to impermanence.”

Stepping out in the sun-dappled terrace, we discover leafy branches melding and merging with the shadows created by Traces, Markus Baenziger’s delicate installation, which literally is a play of shadows, cast on the ground by sunlight, traced and materialised into a sculpture. He says: “Hidden from our attention, these moments are everywhere in nature…. Oversized and fabricated in metal these traces of shadows intend to draw the eyes further so as to experience the delicate beauty found in nature in its entirety.”

Satyabhama Majhi’s vibrant work draws inspiration from the silhouettes of the temple town — with steeples outlined against the horizon — and is actually titled ‘Temple City’.

In the courtyard below, there’s Satyabhama Majhi’s vibrant work that has clearly drawn inspiration from the silhouettes of the temple town — with steeples outlined against the horizon — and is actually titled ‘Temple City’. The elaborate structure in vivid shades of vermillion examines concerns related to urbanisation, migration and memories.

We walk around, only to chance upon ‘Duck Above, Fish Below’, the poetically-titled bamboo installation by Sayantan Maitra. It’s a floating bamboo structure built as a bridge in the waters of a pond. There are shoals of fish swimming in the waters while elegant swans glide gracefully nearby. The artist refers to the present architectural structures that are adjacent to temples and ancient monuments. “There is coexistence of the past and present everywhere human settlement was planned,” he says.

'Duck Above, Fish Below’, the poetically-titled bamboo installation by Sayantan Maitra. It’s a floating bamboo structure built as a bridge in the waters of a pond.

There is in the diverse narratives an affirmation and reiteration of the curatorial theme ‘Navigation is Offline’, that refers to the modern technology-driven societies over reliance on navigational technologies to identify, access and reach destinations. And beyond the patchwork of artworks spread across the trail lays the landscape of a medieval town known for its exquisite temples and palaces. The idea of this juxtaposition of time and destinies is actually possible because the trail is located amidst the remains of the Old Town, where life continues undisturbed. Beneath the ageless Banyan trees, people carry on with their routine existence. Initially, they were curious to see the installations emerge and full of questions but now, they are used to visitors asking for directions. The tea vendors and Mithai Shop are pleased because business has picked up but then the more exciting event is definitely the Men’s Hockey World Cup being held in the town’s newly spruced up stadium. Superstar Shah Rukh Khan is scheduled to arrive. Another draw is a performance by Coke Studio. We have a fleeting run-in with the hockey players when we chance upon the teams accompanied by chief minister Naveen Patnaik at the Mukteshvara Temple where they had gone to seek blessings.

There are these ladders of reality that we encounter on our journey down the trail, and it has to do with the overall experience of living in that moment. In their curatorial note, Panda and Achari write: ‘This is not romanticism of the ‘real’ but a return to the situation where navigation, not only through landscapes, but also through the labyrinth of memories, experiences, and affect was valued and cherished…. Through this project we are attempting to understand such memories,stories,tales and history associated with the people living around this short trail. We as travellers will chronicle its biography. While being in this trail we will retell tales of our own journeys while also listening to the new tales from Bhubaneswar.’

M Pravat's 'The Malleability Of All Things Solid' is deeply embedded in manifestations as well as imaginations of environments. It offers increasingly newer possibilities to imagine space in the contemporary moment

Alongside the labyrinthine path, life goes on at its usual pace and we encounter children peeking in to have a quick look at the art as they make their way to school. Women, freshly bathed, offer prayers at the temples, unperturbed by the art installations that occupy the complex’s courtyard. M Pravat narrates an interesting experience about his time in Bhubaneswar. He says the space given to him (adjoining a temple compound) was used for years as a garbage dump. They needed days to clear and clean the yard before Pravat could make his monumental work, ‘The Malleability Of All Things Solid’. But now, the residents have requested the Artist’s Collective to let the work be a permanent feature, and not to take it away. “My practice is deeply embedded in manifestations as well as imaginations of environments. It offers increasingly newer possibilities to imagine space in the contemporary moment, especially when different utopias are at a collision by an excess of images and virtual spaces.”

Gigi Scaria’s ‘Constructed Realities’ is made with photographs where the existent surroundings are subtly altered.

The response to the curatorial brief was especially thought-provoking when it came to art practitioners who were not local residents. In ‘Wheel of Tradition and Faith’, Arunkumar H.G. created an immense circular wooden wheel-like sculpture. He says, “Faith is something invisible in people unless it is exhibited through signs and symbols, some permanent and others temporary.” Gigi Scaria’s work, ‘Constructed Realities’, is made with photographs where the existent surroundings are subtly altered. The work is a collaborative engagement involving young artists from the city — Deepak Kumar Mandal, Ashish Parida and Radhakanta Turuk — who share their perspectives of the city and the trail. Scaria says this is to understand and document how the younger generation views Old Town and the aspirations of the town’s people who are literally poised between two worlds.

'Temple for Birds’ is Pratul Dash’s marvelously innovative work with terracotta pots.

There are seminars and workshops, performances and dance recitals happening across the city’s many spaces and it is after Dr Nivedita Mohanty’s lecture at Kedarnath Gaveshana Pratisthana that Panda walks us through some of the sites that we had missed seeing through our otherwise packed day in Bhubaneswar. The inky dark waters of Bindu Sagar Lake forms the dramatic foil against most of the art installed around its shores and the effect is quite magical. Our first stop is ‘Temple for Birds’, Pratul Dash’s marvelously innovative work with terracotta pots. Dash says: “This temple, created with clay ‘matkas,’ seeks to celebrate the fragile beauty of nature, to bestow upon the passage of migratory birds, plants and waters a kind of transient permanence. The use of ‘kudua’ or the holy earthen vessel traditionally used for cooking the Maha Prasad at Lingaraja Mandir and elsewhere reiterates a prayer that we must pay heed to the environment. The idea is to shift the work to a park where birds can actually use the pots to build their nests. The mythologies and histories associated with this

ancient city are thus evoked in many varied ways with rhetorical queries and responses.”

Sibanand Bhol's work, a dome-like structure, is inspired by the architecture and craftsmanship of Odisha. Interestingly; it has a perforation through which one can see the silhouette of the glittering Lingaraj Temple.

Sharmila Sawant’s painted text, carving and performance, for instance. Sawant’s work, ‘The Heated Debate’, takes on the form of self-reflective questions that urge the individual to partake in their moral and ethical duties within contemporary society. As argumentative Indians, this is what we do intuitively and we see heated arguments of bystanders who all have a point to make about the work. We see Liminal View under rather different circumstances, far away from the jostling crowds in Guajhar. Located amidst a beautiful herb garden, steps lead us down the narrow paths to this work by Sibanand Bhol, which is illumined by the light of the full moon.

Cecile Beau’s ‘The Vaporous Region’ is a gigantic fish, a ‘Matsya’, with its scales exquisitely fashioned with tiny earthen lamps or ‘diya’

Bhol’s work, a dome-like structure, is inspired by the architecture and craftsmanship of Odisha. Interestingly; it has a perforation through which one can see the silhouette of the glittering Lingaraj Temple. Also evoking allegorical legends of yore, Cecile Beau’s ‘The Vaporous Region’ is a gigantic fish, a ‘Matsya’, with its scales exquisitely fashioned with tiny earthen lamps or ‘diya’. Beau says, somewhat wistfully: “Between earth and cosmos, the Matsya waves towards the water, the temple, and illuminates with his glowing eyes — slightly and literally — the darkness when night comes. On the banks of Bindu Sagar, where this work is placed, the excitement of the onlookers knows no bounds. There is the fragrant scent of diyas in the air and it is as if it is Diwali once more as children and adults alike go closer for a proper look.

It is somehow appropriate that the mapping of the trail finally ends at ‘Shadow City — A Life After’ by Sudarshan Shetty. The skeletal structure is produced with local craftsmen who make objects for various religious and social ceremonies. These structures are created and routinely dismantled after their transient function is over. Mounds of rice lay scattered around this Shunya Ghar, evoking associations of death and emptiness.

Bhubaneswar Art Trail achieves what it had set out to do, quite impressively and in the process, brings together a community of people from the city and far beyond.

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated