Sattriya danseuse Mridusmita Das during the performance of “Madhu Danava Darana”.

The magnetism of a classical dance form is powerful. And Sattriya’s journey beyond Assam has just begun!

"I look different, don’t I?’

Indeed she did. The young mother and PhD student I had met that morning in casual pants and top was dressed in ceremonial dance gear, complete with jewellery that included head ornaments and neck pieces. The costume, and her stance, added a new, unmistakable dignity.

I was in Guwahati to witness and speak at a function organised by Srijanasom, an organisation that is dedicated to the promotion of culture and education. While the evening programme included the handing out of scholarships to three bright young girl students from underprivileged backgrounds, and a lifetime achievement award to Reba Kanta Mohanta, a renowned maker of bamboo-backed masks, I was excited by the fact that the programme included many short pieces of the Sattriya dance.

Despite having lived in Guwahati through my schooling years, and learning the folk dances of the North East, I had no idea about the Sattriya dance. And indeed, it was only in 2000 that the 600-year-old dance form, which is well rooted in the tenets of the Natya Shastra, was awarded the status of a classical dance by the Sangeet Natak Academy. Hidden as it was within the walls of the many monastery like institutions called Sattras, in the state, Sattriya gained the status of a performing art, thanks to the concerted efforts of stalwart Dr Bhupen Hazarika, who added his weight to the movement initiated by Dutta Muktiar Borayan, Maheshwar Neog and Roseswar Saikia Borbayan to popularise the dance. Today, Sattriya, which originated as a means of expression for Vaishnavite worship and was formulated by the 15th century Vaishnavite saint, Shankaradeva, has young women and men as avid students.

Mridusmita Das and Rumi Talukdar depicting Vishnu and Lakshmi respectively in Ananta Sajya from an image in Vishnu Vandana

As the evening rolled out, the dances had me enthralled. Having grown up watching Bharatanatyam, Kathak and Odissi, I could catch gestures and movements common to these dances in the Sattriya pieces. It piqued my curiosity enough. But when I watched my new friend, Mridusmita Das Bora, enact the angst of Arjuna at the battle of Kurukshetra and saw how technology combined with an ancient art to reveal Krishna's Vishwaroopa, I understood why Sattriya was reaching out even to the WhatsApp generation.

The next morning, I sat with Mridusmita to understand more about Sattriya. “It’s pronounced Hotriya,” she informed me. (Assamese does not have the letter s in the alphabet). “And in the past few years, much has been done to lift the dance back to its past glory.” Though Saatriya also delineates the nava rasas, and has pure natya and nritya pieces as well as bhavana in its repertoire, there are aspects that set it apart from the other classical Indian dances, making it indigenously Assamese.

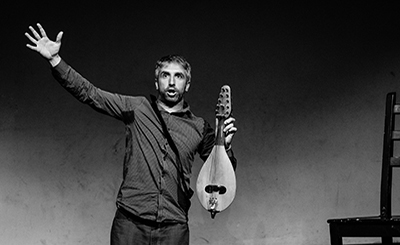

“We dance to music that is called 'bor geet,'” Mridusmita explained. “It has its own raagas and taals, and a movement for recognising the music as classical is underway. The accompanying instruments used are typical too... the khol or drum, the flute, the mridang, the taal and at times, the violin.”

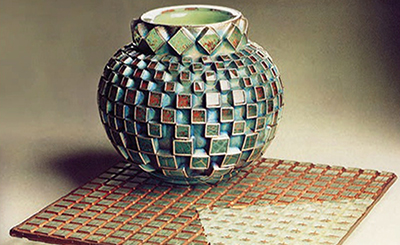

“Our costume is also typically Assamese,” Mridusmita said. “Though through the years, the dancers had started wearing cheap imported material bought in Calcutta, today we wear Assamese muga pat, which is only available here. The costume devised for stage performances includes a blouse, a skirt that could be in either the ghagra or dhoti style, and a chaddar. This was necessary, as women did not dance the Sattriya in the monasteries. The male dancers wear a dhoti and an upper garment held together by a 'kanchi' at the waist, and sport a 'pagree' on the head. As the dance is soft and more expressive than rhythmic, ghungroos are not compulsory.

The jewellery too is traditional, but uses gold washed metal versions. Broad cuffs on the wrists, studded head ornaments and necklaces add richness and glamour to the dancer’s persona.

A group of Sattriya dancers perform a Lashya repertoire, “Gopi Naach"

Much of the dance form has been passed down through the oral tradition, and efforts are on to codify and record the foot movements, as well as the traditional numbers. Mridusmita tells me they follow a treatise called Hastakala, written by Shubhankar Kavi, which details the various hand movements.

Sattriya is to Assam what the Bharatanatyam is to Tamil Nadu, Mridusmita explained. As a child, she had also learnt Bharatanatyam simultaneously with Sattriya. Her present guru, Ramakrishna Talukdar, is not only a fist class first degree holder in Sattriya, but also holds an M Mus degree in Kathak from the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya Mandal, Mumbai.

Mridusmita’s dance training was the result of a vicarious fulfilment of her mother's desire to learn dance, “something she was not allowed to do when she was young.” Today, thanks to her parents, Guru Talukdar has gained one of his most ardent pupils who has performed internationally in Scotland, England, Wales and China besides across India. Equally important is the fact that the one-room space her parents provided the guru to teach their daughter and a few other students spearheaded a renaissance in the dance form. Almost 200 young dancers now hold certificates for completing the arduous training under Guru Talukdar’s strict tutelage. “I was studying in Delhi and needed to concentrate on the dance lessons during vacations, so my parents invited the Guru to stay with us, and teach me,” Mridusmita said, “when the number of students grew, we had to organise alternate space. At one time the fan fell off due to the resonance of so many dancers dancing together.”

Young dancers during a performance of Bhortaal Nritya

As we talked, I remembered the rhythm-based number where groups of young women went through a vigorous routine with mathematical precision of movement that was yet graceful and feminine. Sattriya has attracted students from Tokyo and Belarus, who have come on scholarship to learn from the ICCR empanelled guru.

“But we realise that even a classical dance must stay relevant,” Mridusmita said. “When I am dancing as Arjuna at Kurukshtra, I can see dead people strewn across the battlefield, but to engage the Star Plus generation that watches TV and wants visual drama, we added sound and light effects and back projection. The dance codes are strictly followed, there is no dilution there, but the special effects add to the understanding and interest. Yet, it might seem as if my generation will be the last of professional dancers. Parents are putting pressure on children to train for jobs...”

But one never knows. The magnetism of a classical dance form is powerful. And Sattriya’s journey beyond Assam has just begun!

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated