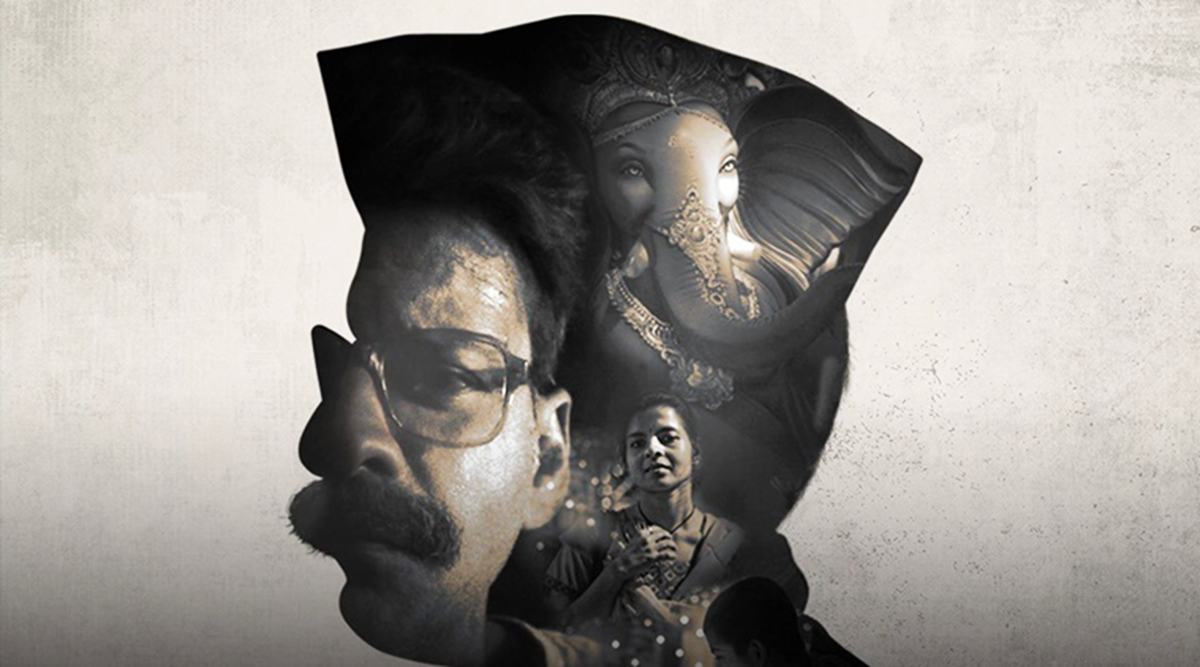

The poster of Devashish Makhija’s Bhonsle. (Below) Manoj Bajpayee in a still from the film.

Devashish Makhija’s recently-released film, which features Manoj Bajpayee in the titular role of a police constable, puts the politics of regional chauvinism, the polarising debates about insiders/outsiders and the ideas of home and belonging in sharp focus

Introduction: God and Man

Devashish Makhija’s recently-released film Bhonsle unfolds over the span of a ten-day Ganesh Chaturthi festival, mainly focussed on a Mumbai chawl. My familiarity with the prominent trope of Durga Puja in Bangla-language and Bengal-centric films made me both curious and a little suspicious about this comparable setting and its symbolic resonance. How would the idol-making, the festivities, worship, crowds, and immersion, play out in this film? Would the titular character, Bhonsle, turn out to be another Vidya from Kahaani? Well, the comparison between the divine and the human is laid out in the very first sequence of the film, with the juxtaposition of two entities — a Ganapati idol that is being painted, clothed, and adorned, and Bhonsle, a havildar (constable) who is taking off his police uniform and hence, un-adorned. As clay is animated with divine energy, the police officer transforms into a commoner. Ganapati is a gentle god, worshipped as auspicious and known as the ‘remover of obstacles’; his presence is ubiquitous across Hindu households and his blessings are sought before any new venture. But the celebration of the Ganesh Chaturthi in Maharashtra has special socio-political connotations that will be evident in the course of the film. Initially, there seems to be little similarity between Ganapati and Bhonsle, and we learn much later that Bhonsle’s first name is Ganpat, a fairly common name for his milieu. He is never a participant amongst the crowds that dance in frenzy before the Ganapati idol, but is once shown worshipping Ganapti by himself in his room and another time sitting in silent companionship before the idol installed in the chawl, after the noise and crowds have subsided — his religion then is a matter of private faith. Like his namesake, he too will prove to be a remover of obstacles. But, like in the film, we will return to this human-divine comparison at the end of this essay.

Native/Migrant

Most obviously, the film is about the politics of regional chauvinism, thus resonating with the proliferating, polarising debates about insiders/outsiders that are today raging across the world. Home and belonging are crucial concerns of our times, and it is no coincidence that important films (like Gulaabo Sitabo and now Bhonsle) reflect them by deploying the metaphor of a shared living space like a haveli/chawl as a microcosm of the nation. More specifically, the direct relevance of the misleadingly termed ‘migrant issue’ that has confronted us at such a massive scale under locked-down India is perhaps what finally gave an impetus for the much-delayed digital release of Bhonsle. In the film, Vilas Dhavle (a terrific Santosh Juvekar), the film’s antagonist, is a taxi driver with political ambitions, who shows up repeatedly to provoke the residents of Churchill Chawl along the incendiary lines of ‘naukri, ration, ghar’ (job, food, shelter) and how the ‘Marathi manoos’ were being robbed of these resources and entitlements because of the influx of the ‘Bhaiyyalog’ or Biharis. He intersperses his tirades with tall promises and cosmetic cleaning drives without showing any investment in more pressing practical issues shared by all, reminiscent of the larger hollow political discourses of cleanliness and development in contemporary India. However, the chawl residents resist his ‘Marathi prestige’ spiel, even though they do not openly defy him.

Dhavle chooses to exploit the occasion of Ganesh Chaturthi as an assertion of cultural dominance, and declares a Marathi-exclusive Ganapati worship at the chawl. He reacts violently when Rajender, a young Bihari man, brings in a Ganapati idol, and a public spat ensues between the two, with Rajender claiming the chawl (and Mumbai and Maharashtra) to be his home and Dhavle vehemently refuting it. After being humiliated and beaten up by Dhavle, Rajender (for once, a mild Abhishek Banerjee) tries, in his own inept ways, to protest against this discriminatory violence. Things get accelerated with the arrival of two Bihari siblings in the chawl next door to Bhonsle. They are the ideal ‘migrants’ — Sita (a quietly effective Ipshita Chakraborty Singh) tries to keep away from the fracas and mind her business, but her kid brother Lalu (a wonderfully expressive young Virat Vaibhav) gets forcibly inducted against his wishes into the opposing camp of ‘Uttar Bharatiya Sangh’ by Rajender. When Sita discovers that Lalu has been coerced into disfiguring the walls of the chawl’s vachanalaya (public reading corner), she promptly takes him to Bhonsle for confession. The film effectively demonstrates how young boys find themselves bullied and indoctrinated into divisive ideologies through rites of initiation based on coercion and violence.

As for Bhonsle himself, he is visibly a staunch Marathi, whether in food or dressing habits. It is not as if Bhonsle is ‘neutral’ in this ‘native/migrant’ dispute, but for the most part he remains aloof, for inscrutable reasons of his own. This is layered by the fact that Bhonsle is played by Manoj Bajpayee, an actor who is himself a Bihari, and has made his career and home in Mumbai. Dhavle’s repeated bids to co-opt Bhonsle in the divisive cause of the Maratha Morcha Party are rebuffed and despite wedging his foot in through Bhonsle’s ajar door, he finds it slammed in his face a few moments later. But it is when Sita takes Lalu along to Bhonsle for confession that we notice the first instance of involvement on his part, in the form of a stern warning that frightens the boy. He steadily grows closer to the two of them in the rest of the film, when they begin to take care of his ailing body. Later, he rises to their defence, paying with his life in the end to avenge Sita’s sexual assault at the hands of Dhavle.

Questions and Comparisons

But read at the literal level, the film leaves us with many niggling questions about its politics. Where does Rajender disappear as the plot progresses — was his role only meant as a catalyst, and a point of contrast to set up the ‘good migrant’, Sita? Would we have been less sympathetic if the characters of Lalu and Sita — a vulnerable child and woman — were absent? What does the contrast between Sita’s ‘feminine’ domain of care as a nurse and Dhavle’s fragile masculinity, achieve, apart from a nod to intersectionality? Why are the themes of sexual violence and vengeance suddenly added to the film? Why does Sita, the only prominent female character in the film, trust Bhonsle despite her recent trauma? Why is the wobbly geriatric avenger in this film male (unlike Makhija’s 2017 previous feature film Ajji)? In other words, why does the film fall back on the trope of the male saviour? In today’s digital content that suddenly abound with ‘good cop’ narratives, is Bhonsle any different? And why is he a retired cop? Why is he pitted against Dhavle and not an adversary more fitting of his stature? To address some of these concerns, we need to shift perspective to the psychological and metaphorical richness of Bhonsle.

Before that, a couple of cinematic comparisons. The surface similarities with Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino (2009) in terms of plot and themes are indeed striking, but the differences, even more so. Primarily, these differences are in terms of characterisation and treatment — with fewer characters, a hauntingly intimate cinematography and its preference for silence over dialogue, Bhonsle’s achievement lies in its depth of character study — of individual persons as well as social structures and values. But the more obvious comparison is with Makhija’s own companion piece, Taandav (2016), a prequel of sorts made to pitch the idea of the longer Bhonsle. There, too, we have the Ganesh Chaturthi and Manoj Bajpayee playing a Marathi police officer, albeit a younger man, Tambe, but the tone of the two films is very different. The two protagonists seem to possess different temperaments, but paring away their superficial variances, there is indeed a continuity — that of repression partly stemming from a strong sense of ethics, and a primal response born out of pent-up frustration and/or anger, with the festival as backdrop. In fact, it is not much of a stretch to imagine Tambe and Bhonsle as alter egos located at different temporal junctures of the same life. Perhaps a Tambe had grown into a Bhonsle? Perhaps his darkly comic taandav is here transformed into a more sinister dance of death, this time truer to its conventional associations? Maybe this is so because Bhonsle, unlike Tambe, finds himself outside the constraints of his uniform? This then is the real ‘extension’ of duty that Bhonsle finds for himself.

Home and Belonging

The film stretches the limits of the insider/outsider debate, for the Bihari ‘migrants’ are by no means the only ‘outsiders’ in this story. Come to think of it, most of us are outsiders to our places of residence. But the film’s strength lies in portraying the alienation that is part of the urban living experience, which makes outsiders of us all in even more fundamental ways. And so, it is not as a tale of the othered migrant that the film captures my interest, but as an exploration of the ‘native’ self. So, what lies behind a self like Dhavle and Bhonsle and in what ways are they outsiders to the worlds they inhabit? This perceptive piece that reads Dhavle and Bhonsle as two ends of the same spectrum is worth expanding upon. Specifically, their ideas of ‘home’ here are important. There is a tragic irony behind the fact that for all his talk of home and outsiders and belonging, Dhavle doesn’t seem to actually have a home. He spends all day in his taxi, probably sleeps in it, uses a public washroom, and is generally unwelcome indoors — whether it is at the party office where he endlessly waits to meet the local leader, or the chawl where he rarely makes progress beyond the open courtyard. And so his yearning for bonding with people he considers ‘apne log’ (his own people) takes the form of incitement against a manufactured enemy whom he promises them protection against; he genuinely seems rooted in this belief and is at a loss when his boss tells him that he has not caught on to the real game. It may well be that his aspirations of a political career stem less from material greed and more from his yearning for affection and respect. He does not appear to have any companions of his age and draws a bunch of teenage boys around to boss them about, but is aware of the tenuous hold he exercises over them. He draws his identity from the world’s perception of him — this is most pointedly visible in the scenes where he is shown rehearsing his conversations, betraying his anxiety over communication. And equally, he constantly finds himself at the brunt of rejection, real or perceived, whether it is his boss’s dismissal and rebuke, or his resentment at the ease of sexual access that his middle-class passengers evidently enjoy. The veneer of civility and probably his brittle self-perception snap when he is demonstrated as a liar by Bhonsle, someone he truly seems to respect.

If the mercurial Dhavle is a blustering bully and an ingratiating nobody by turns, the unflustered Bhonsle keeps his counsel and is in turn respected by everyone for it. In contrast to Dhavle’s need for public affirmation stands the self-imposed isolation of Bhonsle. If Dhavle barges into the open courtyard of the chawl, Bhonsle retreats into himself, and his room. His idea of home is based on his cramped quarters and its familiar grime and he finds himself condemned to the Sisyphean drudgery of sparse, daily living, without communication and meaningful relationships. For him, the only way out of this is a return to police service, the one thing he seems to really care about, initially. This drawing of a sense of self from one’s ‘career’ and finding oneself disoriented upon retirement are integral experiences of modern living that many of us would find relatable. Bhonsle is undergoing an existential crisis himself and withdraws perhaps all the more into his shell to cope with this unsettling new reality. This is deftly captured in an early sequence in the film with its mixture of hyper realistic close documentation of the objects in his room and a surrealistic dream where he has a vision of himself growing old in the repetitive grind of weary discontent. Seen in this light, Bhonsle’s detachment seems not that of the complicit bystander but stems from an impulse of self-preservation: his resistance to being swept up by the chaos around him. We first see this when he changes the station on the radio when it plays a ‘political’ news item — the barely functional radio which is his only link to the world outside his room. And we see it in the remarkable long shot of him walking in a crowded Ganapati procession where his self-containment remains intact even amidst a sea of people. This interiority he inhabits is masterfully portrayed by Manoj Bajpayee’s superbly restrained performance with hardly any speaking lines but an articulate body language and a throbbing silence. (Bajpayee’s performance of lonely paranoia in Dipesh Jain’s 2018 film Gali Guleiyan makes for a good study in comparison and contrast). Bhonsle is in a state of deep isolation and alienation that can make no space for emotional or political involvement with others. And the chaos is not only around him, but also within his body warring against itself that is giving him splitting headaches that will turn out to be symptoms of a brain tumour.

But, slowly, Bhonsle realises how intimately the idea of home is invested in our relationships with people and the mutual care and respect that shows us we are valued. Thus, it is when Sita and Lalu are able to breach this wall of impassiveness through their care and affection, respectful of his private space, that we see him emerge from a stupor of withdrawal. The lesson he learns is also a larger political lesson, one that disrupts the myth of self-sufficiency (atma nirbharta as some would put it). As the film progresses, the door to Bhonsle’s tiny room begins to open more widely, his internal world expanding to make space for his next-door neighbours; gradually, he learns to let them in. The brother-sister pair are, in this sense, the least estranged in this new place, mostly perhaps because they have each other. The film makes space for several animals and birds and insects — both, as metaphoric presences as well as expanding our notion of the city and its population — but importantly,the dog that lies outside Bhonsle’s door is only befriended by Lalu, evidence of a fuller inner life marked by companionship and communication. It is thus fitting that Sita and Lalu act as catalysts for the turn that the personal narrative arcs of Dhavle and Bhonsle are going to take. In the end, Dhavle is not able to overcome his sense of exclusion, but Bhonsle is able to transcend his sense of solipsism. This is what makes them worthy adversaries, and also explains the strange closeness that both men share in their last moments, their bodies lying in a deadly embrace of sorts.

Fathers and Sons

That last visually unsettling sequence of interlocked intimacy between the two men also invites another reading. An interpretation that explains why, after bashing Dhavle’s head to the floor, Bhonsle apologises, strokes his head and urges him to rise, before succumbing to his injuries himself. This is a peculiar mix of parental wrath and tenderness at work here. Travelling back into the film, we realise Dhavle’s particular need for approval from Bhonsle throughout has actually been the need for parental, particularly paternal, approval. The need for an authoritarian father figure is a strong impulse that drives Dhavle and it is worth noting that he is always craving validation from father-substitutes, whether the local leader he calls ‘Bhau’ (brother) or Bhonsle, whom he addresses as ‘Kaka’ (uncle). (The motif of father-son conflict was in fact set up earlier in the film in the form of Rajender’s fraught equation with his father.) Relatedly, for Dhavle who pins his identity on his perceived notions of bloodline, Bhonsle is also the representative of his supposed ancestor, the legendary king Shivaji Bhonsle who is appropriated as an icon by the Marathi manoos discourse. Bhonsle’s public rejection, thus, is devastating to him at several levels. Likewise, Lalu looks up to Bhonsle as a father figure, imitating his posture and in evident awe, respect, and fear of him. Their bond will be sealed when both spend a night in silence, repainting the blackened wall — a very different rite of initiation than the cycle of humiliation and coercion endorsed by Dhavle and Rajender. Sita, too, cares for Bhonsle as a daughter and the depth of their relationship is apparent when despite being traumatised and flinching at his male presence, a frozen Sita allows a distraught Bhonsle to gather her in his arms and comfort her. When Dhavle attacks the innocent Lalu, Bhonsle’s intervention is reminiscent of a father disciplining his son and carry tones of sibling rivalry and jealousy at work. Dhavle’s inability to look him in the eye, and later his cowering and compulsive apology are evocative of a child’s fear of the father’s wrath. Therefore, upon realising that the forgiveness that Bhonsle had shown Lalu is not extended to him, Dhavle turns upon Bhonsle and unleashes his fury upon him. I cannot shake away my discomfort at the inclusion of sexual assault in the film, nor the disappearance of the survivor’s voice and agency succeeding it. But I do concede that sexual violence here is presented not as a matter of violation of female honour but as a consequence of male fragility and to that extent, the film’s vision implies that the ensuing battle has to be fought between competing models of masculinity that share an affinity, even at the cost of personal sacrifice.

Conclusion: God and Man

This brings us back to the note on which this essay began: Ganapati and Ganpat Bhonsle. Here is a god who has been curiously absent throughout despite his ubiquity, more often shown in fragments and askew angles, than wholly, frontally visible. For me the most disquieting image in the film was that of a trunkless Ganapati with a gaping hole in place of mouth, visually resembling a scream. The last sequence of the film returns to a striking alternation between Ganapati and Ganpat, only here both seem to be moving towards the same fate. As a dismembered Ganapati lies discarded as it were, submerged in the dirty seawater post visarjan, a spent Ganpat Bhonsle’s life ebbs away in a tiny public washroom where he has tracked down and killed a guilty Dhavle trying to wash away the evidence of his crime. Bhonsle has lived up to his name by standing up for the proverbial ‘rats’ (the Biharis termed as such by Dhavle) who are also the vehicle of the lord Ganapati. But is there more to the invocation of the divine at this point? In this conversation, Makhija speaks of the idea of crime noir that he had tried to capture in this film as one stemming from ‘the death of god’ — a notion widely prevalent in western philosophy and art. In the film, the pomposity of the festival acts as a temporary cloak on the desolation of anonymous and desiccated city living, and on the dirt and grime of the underbelly of the ‘maximum city’. The festival’s clamour drowns Lalu’s appeals for help. The scene of sexual violence is shown in tandem with feverish dancing in a Ganapati procession, both suggesting an aggressive staking of masculine virility that perceives itself routinely slighted, ignored, affronted.

In short, the very image of god and the ten-day long mega-festival in his name have been used in the film to convey the godlessness of the metropolis. Makhija’s films that seem to glorify extrajudicial revenge stem from a deep philosophical distrust of institutional mechanisms of justice, whether it is the police or the institutionalised religion. One way to read the excessive and intimate nature of violence of the last scene is to see it as a carrier of the anguish of paternal abandonment — of son by father, and of man by god. But another way to read the association between god and man in the film is to see in it not abandonment by an omnipotent god, but an enactment of the internalisation of the morality that we are habituated to transposing onto a divine figure. This is not morality that uses the crutch of religion in a bid to dominate, but morality that draws strength from religion as personal faith, which inspires us to a spiritual understanding of our place in the world and in relation to others. Over the ten days of Ganesh Chaturthi then, Bhonsle has been discovering in quiet communion with his private god this spiritual self — all that lies within us that is capable of unconditional love and compassion for an ‘other’ and which finds its own agency to feel and act on their behalf. As Bhonsle gains consciousness briefly, gasps for air and then presumably dies, much like the washed-up god after whom he is named, we see in him more than in Ganapati a patron deity of the city. Having absorbed in himself the city’s crippling loneliness and the growing tumour of its multiple forms of violence, but also having experienced the sudden deep attachments it can bestow, he descends in one heroic swoop upon an agent of the its disintegration. The film’s poster with Bhonsle’s profile subsuming a smaller version of himself, Sita, Lalu, and Ganapati, conveys the same reading. Hence, to me, the charge of the climactic violence arises from its being a dramatisation of an internal struggle within Bhonsle that he manages to resolve, not to be rewarded with mortal life, but with a private, ethical triumph unwitnessed by anyone else. In that sense, strangely enough, the film’s dark ending is actually its article of faith in humanity and all that a human soul can feel and act upon, even in the bleakest circumstances, frailest forms, and with only a wretched death in sight.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated