Ishaan Khatter as Maan Kapoor and Tabu as Saeeda Bai in a still from Mira Nair’s adaptation of Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy for the BBC

Had the literary aspects of the novel been retained in the adaptation for the BBC, they might have been an important metaphor of the Indianness of English, and postcoloniality

To the Lighthouse (1927), a novel by Virginia Woolf, has a section called ‘Time Passes,’ that describes the events of ten years in twenty pages. Perhaps the writers of the BBC’s adaptation of Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy (1993) might have looked to her for hints on time management, in order to fit its 1,400 pages or so into six hour-long episodes. To the Lighthouse might also be called a study in the intensity of perception; they matter more than traditional parametres of plot and character arcs. This cannot be said of A Suitable Boy, in which time is represented realistically, rather than subjectively.

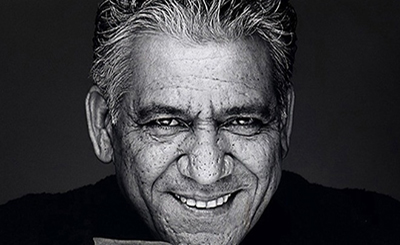

And that is why, said Mira Nair, the director of the adaptation for the BBC, in a podcast interview with The Economist (August 2020) that vast lengths of the novel had to be cut back in order to accommodate the series. A reader of the novel would fear for its aura of authenticity. Myriad details could be lost; apart from its broad canvas, the novel luxuriates in nuanced descriptions of daily life; and of inner psychological worlds. Mahesh Kapoor (Ram Kapoor) tends to be homophobic and displays frequent bouts of volatility, but we also read of his close and warm friendship with the Nawab of Baitar (Aamir Bashir). Maan Kapoor’s (Ishaan Khatter) relationships with other friends (not just Firoz, played by Shubham Saraf) is layered with romantic love. The Nawab is close to his family, and grandsons (not present in the adaptation) — and so on. In short, we read much more than we can ever hope to watch on screen. Reading requires intellectual effort and concentration. Television, with its dictates of a week-end ‘slot’, robs us of a sense of immersion that books give us. From early on, the beautiful lines of Seth’s prose are replaced with trite lines and sentimentality. The overly clean streets and mohallas, the bright silk saris and jewellery — one has to wonder if the adaptation is catering to globalised tastes.

Tanya Maniktala as Lata Mehra

Ironically, A Suitable Boy, set in 1950s India, had more readers in the West when it was first published: Brahmpur, the fictitious setting of A Suitable Boy, is flush with the cosmopolitanism of university-educated youth. It is a world steeped in the English language, and literature. The BBC’s airing of a show with an all-brown cast — A Suitable Boy — was a first for them. Whether or not the Western world is aware of postcolonial attitudes to English, the language has been claimed as its own in the postcolonial world. Indian postcolonial writing has existed since the nineteenth century; and is perhaps traceable to the eighteenth century. A Suitable Boy, like those early writings, is a reclamation of a world: it represents a society and culture ‘of our own’; (to paraphrase the postcolonial manifesto of ‘a literature of our own). Lata’s understanding of life and love are gleaned from literature. Had the literary aspects of the novel been retained in the adaptation, they might have been an important metaphor of the Indianness of English, and postcoloniality. Otherwise, Indian English (of the adaptation) could be, as recent criticism has proven, odd.

When Netflix aired A Suitable Boy in India, it was in another, altogether different political context from the BBC’s airing. This decade might be said to represent the middle-class’s mainstreaming of protest — never before has India seen the numbers gathering to support minorities, farmers, women, and the marginalised; who resist the grand narrative of the nation, entwined as it is with Hindutva ideology. Surely, it behoves the adaptation to engage with them. It is, however, more intent on addressing the tensions between Hindus and Muslims; the eruption of violence near Misri Mandi, and later on during Dussehra and Muharram. Seth picks out the threads of myth and history that indicate that the monoliths of Hinduism and Islam have been in conflict for centuries, sometimes sparked off by caste oppression. These details are lost in the adaptation; the violence is a ‘backdrop’ to the story. When Lata Mehra (Tanya Maniktala), the protagonist, and Kabir Durrani (Danesh Razvi) fall in love, Lata’s friend Malati (Sharvari Deshpande) warns her that it is “too dangerous” a time for love after she finds out that Kabir is a Muslim. That line changes the precise nature of Lata and Kabir’s relationship drastically from the novel, where even if dogged by caution, is never threatened by violence. In fact, Malati, much later, says the very opposite — that it is dangerous to think of others in terms of their religious identity.

Danesh Razvi as Kabir Durrani with Tanya as Lata

The novel also unveils the truth of India’s civilisational hybridity — the commingling of the cultures of Hinduism and Islam. In the novel, the mehfils of Saeeda Bai (Tabu) are an unveiling of this underlying mutuality of Hindus and Muslims; reminiscent of an older modernity. She sings to an audience that would have contained both communities: ‘After a wakeful night outside that lane/The breeze of morning stirs the scented air.

Interpretation’s gate is closed and barred/But I go through and neither know nor care.’

And twenty voices repeat after her.

We are drawn, in the adaptation, into the sensuous enjoyment of images and sound that borders on the exoticisation of Islamic culture — bright colours and a languid, effete existence. And a shock — Ustad Majeed Khan (Shujaat Husain Khan) plays the sitar instead of singing his raags. Gone also is the participatory quality of the mehfils.

The relationship of Lata and Kabir is eroticised in the adaptation, but the complexities of Lata’s reactions are left unexplored. Erotic tropes seem to be the way out of representing different layers of the relationship between Saeeda Bai and Maan. We get hints of Saeeda Bai’s abjection — what Bulgarian-French philosopher Julia Kristeva describes as a state of being cast off from the established, communal order of society — mostly through the ghazals she sings. The utilitarianism of tawaifhood does little to alleviate it. In the novel, Maan, too, faces abjection through the loss of caste. These serious concerns, however, are lost in the adaptation — it is the grand romantic gesture that it is interested in. Audience reactions might however, be unpredictable: the scenes might well spark off accusations of love-jihad in the mind of the Hindu right viewer. The kissing scene in the temple, for instance, has already done it.

As in the novels of Tolstoy and George Eliot that it was compared to when it was first published, the plot in A Suitable Boy is structured around the family: it is the middle-class point of view, poised between the subaltern and the Hindu right that takes predominance in the novel. Rupa Mehra is its most vociferous defender. Family life in Brahmpur is enfolded in tradition — the celebration of festivals — Karthik and Janmashtami and Karva Chauth. These descriptions in the novel are a subtle representation of the antiquity of Indian civilisation; a means of reclaiming the past, which might have been lost due to colonialism. The adaptation tends to skim over these textures of the past, as exposition. The precarity of tradition is only sketchily explored through Arun Mehra’s (Vivek Gomber) Anglophilia and his wife Meenakshi’s (Shahana Goswami) sexual promiscuity. Since we do not see the marriage at close quarters, we wonder what the point was all about.

History does not affect daily life in the novel, yet each character is caught up in it, as a nation is stirred to life. The right wing is on the rise. There is the ubiquity of caste-oppression. Servants crawl everywhere — cooks, gardeners and rickshaw pullers in a peripheral narrative that has almost nothing to do with the plot. As German philosopher Theodor Adorno points out, television is more interested in preserving the status quo of class structures. There is a hardening of the middle-class perspective, especially so in the adaptation. The Nehruvian vision of scientific and material progress is strengthened by middle-class conservatism. Lata cannot afford to upset this apple-cart.

Life in rural India, too, is seen through the point of view of the middle and upper classes; more particularly through the eyes of Maan when he goes to Rudhia with Rasheed (Vijay Varma), and later with his father Mahesh Kapoor to campaign for the elections. The passing of the Zamindari Abolition Act — which might be said to be one of postcolonial affirmation — has not yet impacted the grassroots level.

Perhaps it is in the figure of Rasheed that we encounter a serious attempt to address issues of justice. The first to be educated in his family, he seeks justice for farmer-labourers. He seeks to re-instate the farmer Kachcheru with land that he and his family have worked on for generations. We do not see the entirety of his story in the adaptation. We do not also see Jagat Ram, the tanner, who gives a searing critique of Gandhi — he would have provided the all-important Ambedkarite perspective.

The poor are romanticised in the adaptation in order to show how life is in rural India — they sing songs, and work very hard. But their voices remain unheard. This is one of the adaptation’s biggest absences.

The familial Muslim world in the novel is centred around one principal family, of the Khans. The Islamic world of the novel, too, is steeped in tradition and its own rhythms of festivities. But the threat it faces is different — of being pushed to the sidelines. The Nawab remains a shadowy figure, whose dark secret comes to be revealed in a dramatic turn of events.

Aamir Bashir as Nawab of Baitar and Shubham Saraf as his son Firoz

Neither the novel, nor the adaptation, seem to notice the fading away of the Muslim characters. We do not see the unravelling of Rasheed’s relationship with his wife and father; Kabir, too, remains an enigma. Nehru embraces the former members of the Muslim League, even so, the figure of the mad, or unhappy Muslim haunts the pages of the novel, and the adaptation follows suit.

We do not also hear the voice of Begum Abida Khan, the Nawab of Baitar’s sister-in-law, who had declined to follow her husband to Pakistan, staying back in Brahmpur to tend to her interest in politics. This strong, if controversial, female Muslim voice would have provided a necessary contrast to most of the representations of women in the adaptation as wives or mothers; or love-interests. We also don’t see the feminist and socialist sides of Malati, Lata’s best friend. The adaptation’s idea that Lata finds her voice as the new nation comes to find itself, might have been more credible had there been an ethos of female emancipation.

The adaptation glosses over much of Lata’s conflicts about love. Hers is a journey of one of the most tortuous denials of love, in literature. She chooses the path of ‘calmer love’ as a direct result of her uncertainty, tinged with sexual fear. If Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary were not afraid to push against prescribed boundaries of behaviour, Lata Mehra stands out as singularly restrained.

Namit Das as Haresh Khanna

Adaptation might be seen as a kind of translation from the written text to the visual text. And while the writers of adaptations are free to make their own deviations, there are also certain limits to which dialogues or cameos can be tweaked. Those who have ‘read’ Lata will know her as astutely observant of her own and others’ condition in life. But on television, Lata is the unquestioning good girl — good-looking and who comes around to a sensible course of action, rather than an exploration of what Adorno calls ‘sensuous freedom and happiness.’ Haresh Khanna (Namit Das) is ‘constructed’ as the ideal candidate whom Lata falls in love with.

Lata experiences contentment at the end of the novel, but there are also hints of loneliness. The adaptation shows her in the light of finding her “happily ever after,” succumbing to a feel-good ending that will not disappoint the viewer. And that is how we are called to cheer the death of perception.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated