Stand-up comedian Munawar Faruqui. Photo courtesy of YouTube

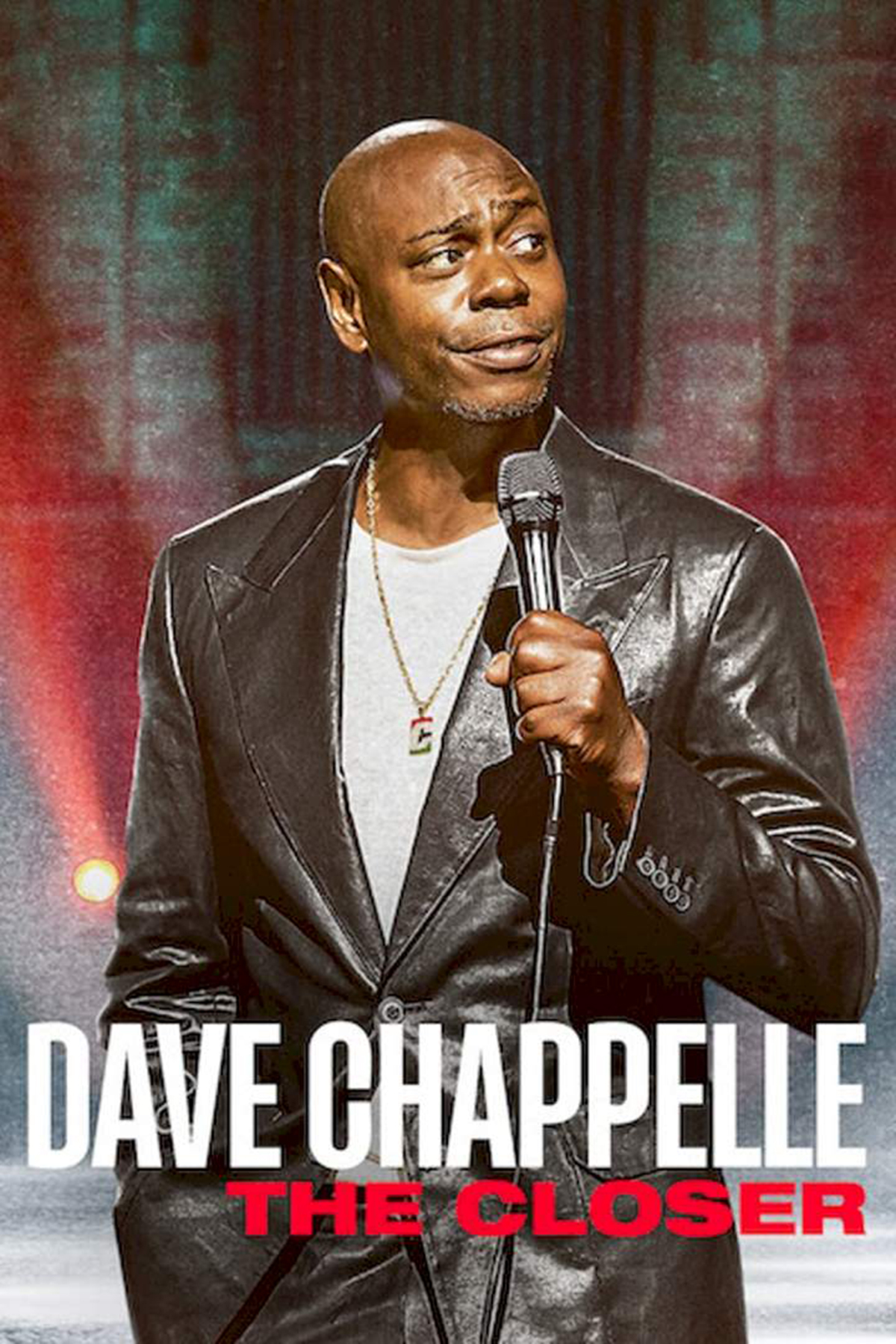

The backlash against Dave Chappelle in the US around his Netflix show The Closer and Faruqui for “hurting religious sentiments” is contextually so different and yet seem to be rooted in a more basic conflict around comedy

Recently, American stand-up comedian Dave Chappelle was at the centre of a row for his Netflix show, The Closer. The show faced backlash from a certain section who believed that it was disrespectful to the transgender community. They argued that Netflix should not endorse content that attacks an already marginalized group. Chappelle, in his defense, countered that he did not make fun of the trans community. However, some people on the side of Chappelle, asked: What if he did? There is a line of thought that believes in punching in any direction, claiming that “funny is funny”. This means that they want jokes to transcend the criterion of moral judgments. This incident involved a rich, powerful, Muslim, straight Black man in America. He never actually got cancelled from anywhere. People did protest and shared their disapproval about his show. Those who opposed him were considered “left- leaning” progressives out to curb free speech by pushing cancel culture. Another section felt that Chappelle was not even that funny, and that he might be deliberately pushing the line to get attention.

Closer home in India, we have a rising comedian Munawar Faruqui, originally from Junagadh in Gujarat and a resident of Dongri in Mumbai, who seems to be heading nowhere. This is the 12th time in the last two months that his show got canceled. The recent cancellation happened because the Bengaluru police advised the organizers against it. They stated that Faruqui is controversial and his performance could disturb law and order. It all started as comments below his YouTube video. Then those comments were elaborated in separate YouTube videos that ranged from criticism of his content to threats against him. And, finally, in January this year, a group of people in Indore (MP), led by the secretary of the state unit of Bharatiya Janata Yuva Morcha, arrived at the venue and got Faruqui arrested on the charge that his content (his previous videos) “hurt religious sentiments”. Having spent 38 days behind bars, he was released on February 5, after the Supreme Court granted him interim bail. Even when he was in jail, the Prayagraj police in Uttar Pradesh had also expressed their wish to summon him.

Faruqui has publicly denied the charge of intentionally hurting anyone’s religious sentiment. If anyone still feels that way, he has apologized. People who support Faruqui link his cancellation to the “new India”, where freedom of speech is under threat and Muslims are targeted for any sign of non-conformism. People who oppose Faruqui feel that their community (Hindu) and its religious beliefs have been a matter of ridicule for long. More than just Faruqui, they seem to be responding to what they call the “liberal hypocrisy” that thrives on “Hindu hate and Muslim appeasement”. This group feels that being anti-Hindu is a fashion in the country and should be stopped. Such groups may invoke Zakir Khan, as an example, because his jokes are mostly based on his identity as a male (“sakht launda”), middle-class, small-towner rather than being on his religious identity.

Faruqui is not really cancelled in the way the word is used in popular discourse. Cancellation is more of a “social’ boycott”. Unlike the transgender community in the US, the community offended in India seems to have a strong connection with the state. Faruqui is being persecuted by the state machinery. By arresting him on the basis of what doesn’t look like “evidence” and by not providing security to his “livelihood” (a Constitutional right) against those threatening violence, the state seems to be in an active collusion with those calling for the cancellation of Faruqui’s shows. For Chappelle, cancellation was at best a private affair. Maybe, Netflix would have cancelled his contract if enough pressure was mounted on them. Maybe some other organizations would have uninvited Chappelle for his opinions. Not that social cancellation is a joke, but it is in Faruqui’s case. In the face of the controversy, Chappelle refused to back out and called for a dialogue on his own terms. Faruqui, on the other hand, seems to have given up. On November 29, the 29-year-old Faruqui announced that he would quit comedy. “Nafrat jeet gai, artist haar gaya (Hate has won, the artist has lost). I’m done! Goodbye,” he wrote on Instagram, after his Bengaluru show, “Dongri to Nowhere”, scheduled at the Good Shepherd Auditorium, got cancelled. “Putting me in the jail for the joke I never did to cancelling my shows which has nothing problematic in it. This is unfair… We do have censor certificate of the show and it’s clearly nothing problematic in the show!” he added.

In the recent past, comedians have enjoyed more attention than they would have wanted and, sometimes, even deserved. This is probably because comedy is the most watched genre of content on platforms like YouTube and Netflix. This implies that comedians do have some power to influence people in the guise of laughter. This does not make people who don’t like comedy or have alternate purposes around public discourse smile. Historically, some philosophers have argued that comedy has a tendency to appeal to our base desires and thus should be controlled. On the other hand, who can deny the significance of humour in society? The Greeks had a Muse dedicated to comedy — Thalia, the patron of comedy. Natya Shastra, the Sanskrit treatise on the performing arts, associates the deity of Pramatha with hasya (comedy). The modern regulators of comedy often remind comedians that freedom of speech is not absolute. This means that comedians are as responsible as anyone else in terms of what they say. Comedians, on the other hand, define their sole responsibility to be relentlessly pushing the envelope of what is considered acceptable. Different contexts seem to adapt this inherent antagonism into their own cultural wars and political battles effectively. The backlash against Chappelle and Faruqui is contextually so different and yet seem to be rooted in a more basic conflict around comedy.

As a laugher, I have always lived this conflict. There is always an urge to be laughing at things which I shouldn’t be laughing at. The comical and the ethical are not the best of friends. For instance, in school we couldn’t help but laugh at my Hindi teacher who use to pronounce the number 14 as “choda” (fuck). The consequence of laughter was punishment. The consequence of our punishment was laughter for other classmates. In hindsight, it was perverse, stupid and even derogatory to be laughing at my teachers’ pronunciation. In hindsight, the teacher also seems to have abused his power. Talking of school, I also had a teacher who once scolded a girl for laughing too much and too loudly. She said, “A girl’s laughter was responsible for the whole Mahabharat.” Laughing at oneself is often posited as a virtue, signalling it to be a sign of security. And, yet, laughing at oneself could also be a low key sign of self deprecatory nihilism. Sometimes, the most dangerous terrain is laughing at something that relates to your romantic partners. The only defense in such a situation is to claim that laughter is an act of intimacy. This is a little twisted. Because one is claiming that even if my laughter feels cruel to you, for me it’s a gesture of love. Sometimes, people may buy this. But sometimes, as Faruqui stated on his Instagram, nafrat (hate) may have the last laugh.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated