Shehan Karunatilaka. Photo: Penguin Random House India

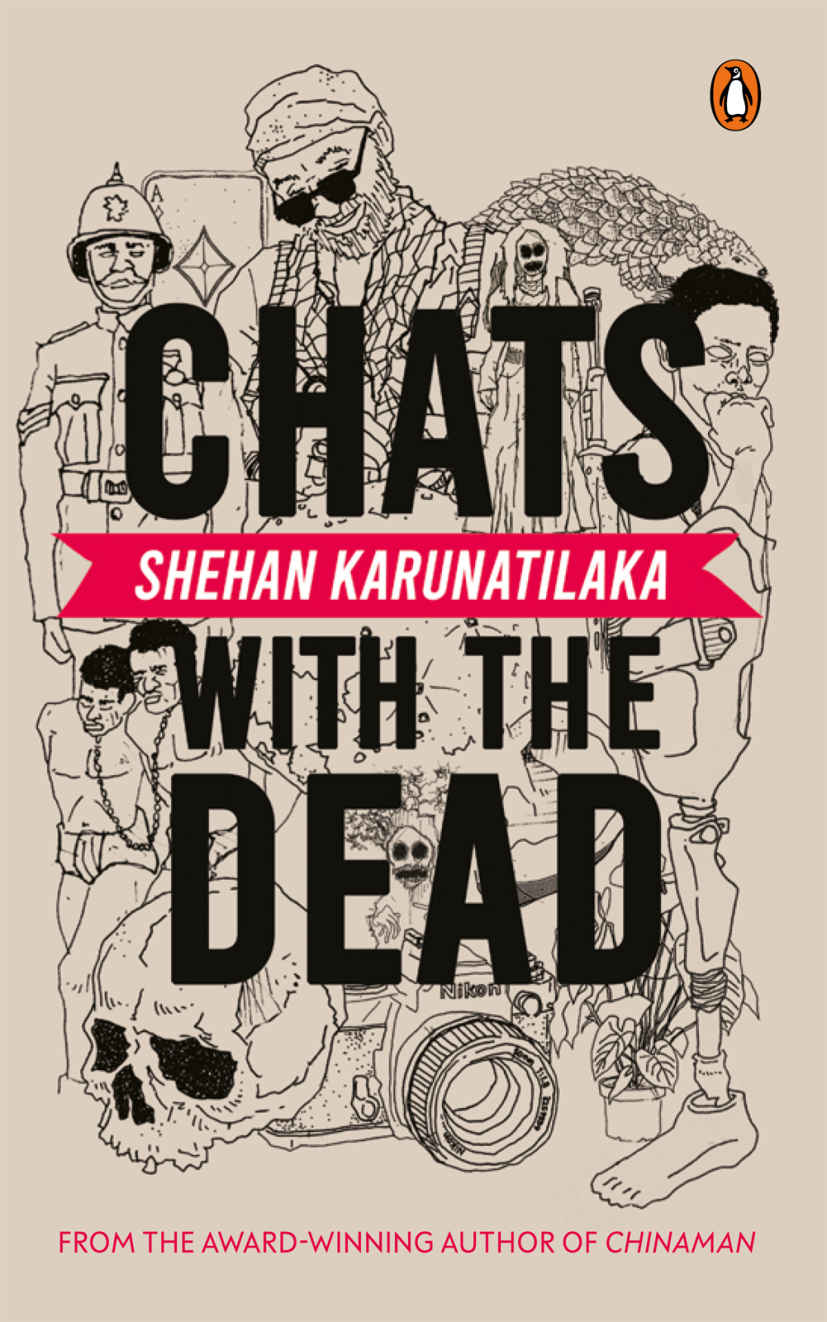

“Evil is not what we should fear. Fuckers with power acting in their own interest: That is what should make us shiver.” That is one of the many conclusions of the murdered Sri Lankan war photographer, Malinda Almeida, who comes to life in Shehan Karunatilaka’s scintillating second novel, Chats with the Dead (Penguin Random House, 2020), a thriller that contains within its pages both the absurdity of life and death and all that keeps hovering somewhere in the in-between.

We meet the photographer when the novel, set during the peak of the Sri Lankan civil war (from 1983 to 2009), opens and Almeida describes the dualities of his life. “If you had a business card, this is what it would say: Maali Almeida. Photographer. Gambler. Slut. If you had a gravestone, it would say: Malinda Albert Kabalana, 1955-1989.” The rest of the novel — divided into seven moons (nights) to show the soul’s journey to the next realms — sees Almeida wading through red-tapism in order to see himself arrive in the realm of The Light, which is not exactly heaven, but somewhere close.

Told in second-person, the novel explores what the afterlife is like for those killed in war — with no gravestones. In Karunatilaka’s version of the afterlife, there are throngs of bruised, broken bodies — many with no heads or limbs — stumbling through corridors, standing in queues at unending counters, their souls wafting from one level to another, moving in circles, thanks to the whorls of red tape that seem to have followed them. “There is a corpse every second. Sometimes two.” Who killed them? The LTTE? The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP)? The Sri Lankan army? Or the Indian army? Nobody can be sure of that, except for the ghosts themselves. “The afterlife is a tax office and everyone wants their rebate,” Almeida says.

Life is but a “flicker of light between two long sleeps.” Almeida has to solve the mystery of his own death. His situation is compounded by his dualities and contradictions of his character. The fact that he has been witness to crimes that no one has seen. Also the fact that thoughts, conclusions and and realisations keep hitting him with their gentle but stark ferocity. Somewhere early in the novel, he has one such thought: “More terrible than this savage island, than this godless planet, than this bored universe, than this tennis ball at 23.45. What if, all this while, asleep is what you have been? And from this moment forth, you, Malinda Almeida, photographer, gambler, slut, will never get to close your eyes ever again.”

Early on in the novel, Almeida, an atheist who sees himself as having been reduced to a voice in his head after he dies, tries to explain the “world’s madness” by philosphising in the light of his lived experiences and choice: “If there’s a heavenly father, he must be like your father: absent, lazy and possibly evil. For atheists, there are only moral choices. Accept that we are alone and strive to create heaven here on earth. Or accept that no one’s watching and do whatever the hell you like. The latter is by far easier.”

The novel, says Karunatilaka, became an exercise in imagining what Sri Lanka’s dead would say if they could be heard. In Sri Lanka, and in South Asia, he says, there’s plenty to write about. “Not all of it is pleasant, though a lot of it is humourous and absurd and, therefore, ripe for dark comedy. You’ve never been stuck for material. You just have to decide which absurdity to write about,” says the author.

Excerpts from an interview:

Shireen Quadri: Chats with the Dead is the story of a young war photographer, Malinda Almeida or Malinda Albert Kabalana, whose ghost roams about the in-between world during the course of the novel, which is set in the war-torn Sri Lanka of 1989. A kind of a zen book for the afterlife, it subverts the idea of the afterlife glorified by all religions and the popular belief that we go to a better place when we die. Were you interested in a conversation with the ghosts of Sri Lanka’s past?

Shehan Karunatilaka: It started off as a run-of-the-mill ghost story, but the ghosts gradually grew more political as I got to know them. Sri Lanka’s recent history is littered with homicides, some famous, most anonymous. We’ve had many wars and too many unmarked graves and if ghosts exist, then Sri Lanka must be swarming with them. The novel became an exercise in imagining what Sri Lanka’s dead would say if they could be heard.

Shireen Quadri: Even though Chats with the Dead aims to straddle a different course than your fascinating debut, Chinaman (2012), in a larger sense, it seems to have emerged from the same continuum of ideas — both Chinaman and Chats with the Dead deals with the dead coming to life and the living coming to death, as well as what it means to have lived. Do you see both these novels as reflection of your preoccupation with making the invisible visible and giving a voice to those who are no longer there, and exploring the “flicker of light between two long sleeps”?

Shehan Karunatilaka: You’re never aware of the similarities when you’re writing, and, on the surface, a ghost story and a cricket story would seem worlds apart. But you’re right, they are cut from the same cloth and have similar thematic concerns. I guess like most writers I’m doomed to write the same book over and over. But I do like the idea to giving voice to those who no longer have one. Makes the work seem much loftier than the cricket matches and horror movies that inspired it.

Shireen Quadri: Chats with the Dead, unlike Chinaman, is a whodunit wherein Malinda has to solve the mystery of his own murder since he can hardly recollect how he died. Even though the story sounds like a thriller, your treatment makes it so far removed from a mere thriller, and makes it a novel suffused in sardonic humour. Did you have to work a great deal on getting its tone right?

Shehan Karunatilaka: It took several drafts to get the plot and tone right. Thrillers are hard work, especially when you’re using well-worn tropes. But the book doesn’t exist until you stumble upon the voice of it. And that’s something you can’t really force. I think exploring the second-person narrative and the psyche of a gambler helped.

Shireen Quadri: Chinaman, which centered around a neglected figure of the Sri Lankan cricket, PS Mathew, and a fading alcoholic journalist WG Karunasena’s obsession of chronicling his life, also had its gaze on several other strands of life in the island nation — the relationships between old men, father and son, husband and wife; the depradations of power and the ruinations of the game of cricket; the ethnic conflagrations — all this laced with a dash of tragicomedy. In Chats with the Dead, you do something similar, evoking the corruption and red-tapism, the deplorable human rights violations, the questionable intent of NGOs, and the nexus between the government, shady individuals and the police? Do you see your fiction as mirroring some of Sri Lanka’s, and a large part of South Asian, realities?

Shehan Karunatilaka: There’s plenty to write about in Sri Lanka and South Asia. Not all of it is pleasant, though a lot of it is humourous and absurd and, therefore, ripe for dark comedy. You’ve never been stuck for material. You just have to decide which absurdity to write about.

Shireen Quadri: You imbue Malinda’s character, an atheist and a closet gay, with many layers and, through him, explore how life could have been for same-sex couples in the Sri Lanka of the late Eighties, with the Civil War raging at its peak. Do you see the vocation and sexuality of your protagonist as vital to your narrative arc?

Shehan Karunatilaka: The undercover nature of his romantic life mirrored that of his professional life. The more I wrote about him, the more interested I was in his contradictions. He enjoyed a promiscuous sex life, despite being closeted to the point of denial. He took calculated risks at the casino but made reckless decisions in the war zone. Being a war photographer informed his compassionate world view, but may also have got him killed.

Shireen Quadri: While Chinaman only alluded to the war, The Chats… engages with it a bit more directly. Did the novel’s structure and the need for plot necessitate this?

Shehan Karunatilaka: Both were very conscious decisions. The challenge of Chinaman was to write a Sri Lankan novel set in the 80s and 90s that completely avoided the war. A story that celebrated life in the island, despite being set in a turbulent time.

With Chats…, it was the opposite. Here, the intention was to stare into paradise’s black heart and to try to find a metaphysical explanation for why some say this island is cursed.

Shireen Quadri: The tone of dark humour that echoes through your work and the jaded worldview of your characters is reminiscent of several writers, both in the past and present. Could you name some of them? How do you see them, especially Vonnegut, influencing your style?

Shehan Karunatilaka: Kurt Vonnegut’s ability to wrap a depressing truth in a joke is something I aspire to. Others who do it brilliantly for me are Douglas Adams, Margaret Atwood and George Saunders.

I also read a bit of Cormac McCarthy and Ernest Hemingway, neither of whom are particularly jokey, but both excel at finding the poetry in violence and despair. And Bill Bryson, PJ O’Rourke, Dave Barry, Chuck Palahnuik, all manage to mix humour with varying degrees of nihilism.

Shireen Quadri: You have also written advertisement jingles, rock songs, travel stories and, even, basslines. We hear you are working on a short story collection now. How is the process of writing in such a variety of forms? Where do you place fiction-writing among all these forms?

Shehan Karunatilaka: I think it’s all the same tools and similar processes. You’re still using a pencil and paper and some of your brain and, hopefully, a bit of your heart. I go through the same stages of excitement, terror, procrastination, scribbling and relief whether I’m writing ad copy, or kids’ stories, or travel pieces. Journalism is hard and requires diligence that sometimes eludes me. Music is pure, but requires talent that I don’t have. Ad work is stressful, but ultimately the thing that pays my bills. Fiction is the thing that makes me sad if I don’t get to do it. So, I try and slot it in amidst all the other scribblings.

Shireen Quadri: Sri Lanka has been fortunate to have some brilliant storytellers, including Gunesekera, who continue to tell its story in so many ways — the stories of lives caught in the throes of war, of people with scarred memory, of disappearance, displacement, disillusion and disorientation. What is the story of Sri Lanka of today? What overarching themes do you see contemporary writers dwelling on in their writing?

Shehan Karunatilaka: I’ve been more moved by local theatre than by fiction in recent years. The Sri Lankan stage has attracted diverse voices in all our languages and isn’t shy of experimentation or contentious topics.

I’ve also noticed a wave of young science fiction writers who’ve emerged in recent years, for which I think, it’s about time. Especially since the greatest Sri Lankan writer in my opinion was Sir Arthur C. Clarke, who lived here for longer than I have.

I’d like to see more stories come out from inside of the war zone. We’ve had a few but not enough for me. Maybe a generation has to pass before we can examine our past without fear.

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated