.png)

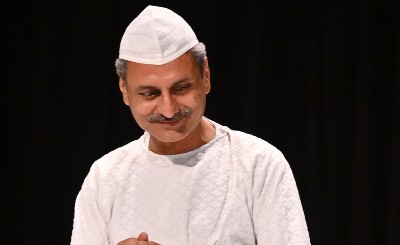

2024 marks the birth centenary of Kalpathi Ganpathi Subramanyan (1924-2016), one of India’s most influential modern artists, who moved fluidly between painting, sculpture, mural art, and writing. Photo courtesy of Saffronart and Krishen Khanna

This wide-ranging, in-depth interview with the Modernist master — whose birth centenary is being celebrated this year — was long lost to time and has been salvaged from a reporter’s archive. It reveals his insights into art, politics, and teaching. The artist underlines the importance of experimentation, the relationship between artist and his material, and the power of art beyond formal education

Manjula Narayan: Your body of work has been so extensive. What have you enjoyed doing the most?

Kalpathi Ganpathi Subramanyan: Well, if I didn’t enjoy doing all of them, I would not have done them. Whatever kind of work I engage in, I always find joy in the process. In fact, I work across various media because I see each medium as a challenge. So, to answer your question, I can’t say that I enjoy one more than the other — they all serve a purpose. Every artist, whether working within a single medium or across many, does so out of a certain compulsion, an inner need. That’s the driving force behind the work, and that’s how it should be understood.

MN: How did your time as Deputy Director at the weavers’ service centres shape your understanding of craft practices in India and influence your broader artistic journey?

KGS: My work with weavers wasn’t initially part of my artistic quest; rather, it stemmed from a desire to understand the broader landscape of craft practice in India. This is largely because I believed that the scope of art practice here was much wider than what city-bred critics typically discussed, and I wanted to experience it firsthand. Some people thought I would do a lot of good work at the weavers’ service centres, and I took on the role of Deputy Director for a while. I spent about two years and a few months there. The main outcome of that experience was that I had gained a clearer understanding of artisan practices, along with a deeper insight into the challenges surrounding craft development and education.

MN: How did the MSU Faculty of Fine Arts’ fair and your collaborations, such as with Gyarsilal Mistry, influence your creative process and lead you to explore different mediums like toy-making and terracotta?

KGS: They all came from different situations. I started making toys while teaching here. A colleague mentioned that teaching art had become too dry and repetitive, so we thought of organising a mela every year. This would not only invite the public to see our work but also offer them something accessible to buy, bringing art closer to what people could have in their homes. That’s how we started the Fine Arts fair, where the artists designed toys, calendars, puppets, and held small stage shows. However, the fair has not happened for a while; the last one I saw was five years ago. Since then, it hasn’t been held.

.jpg)

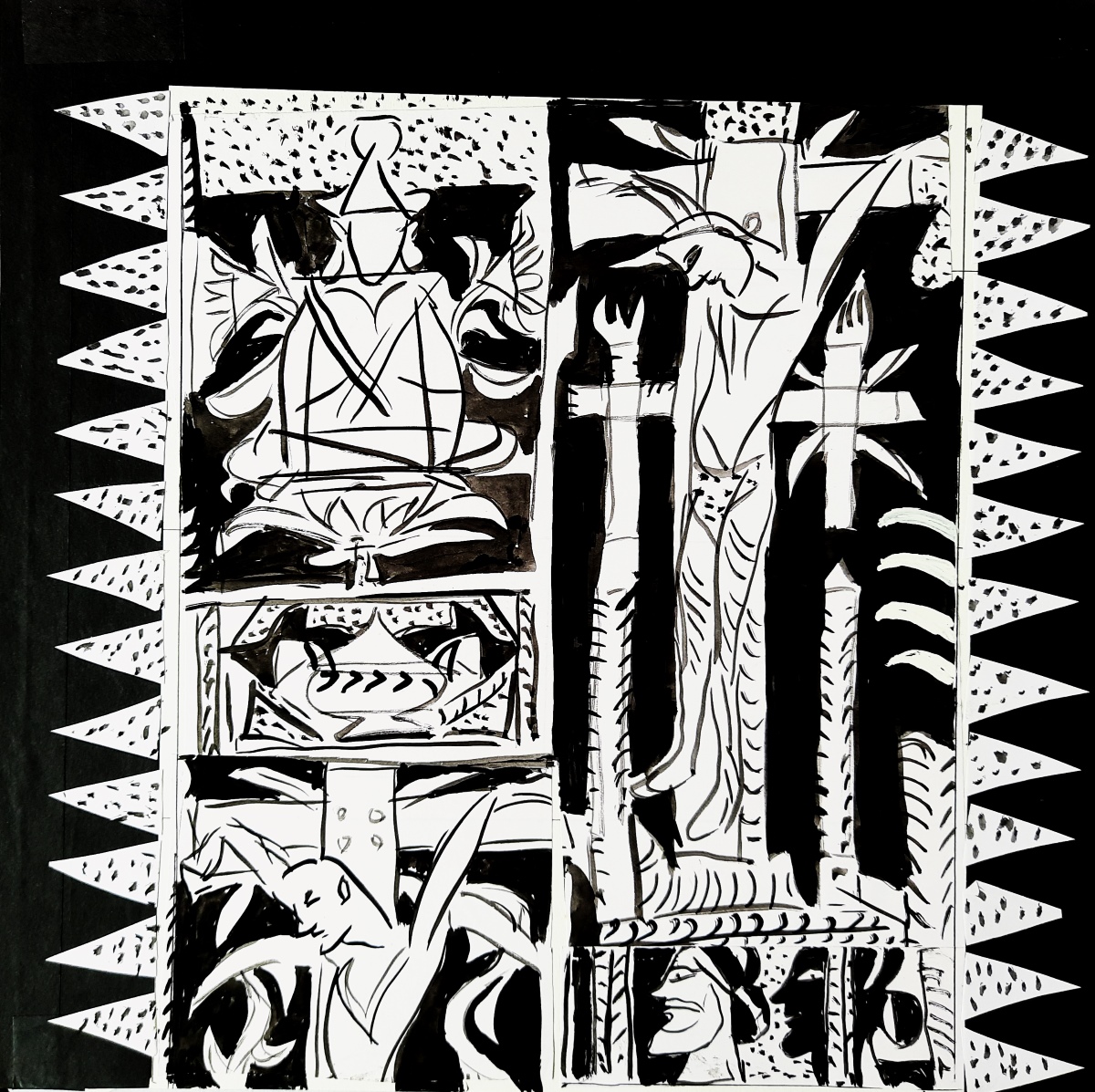

A painting by K.G. Subramanyan

Now, artists have become more professional. They focus on what they’re going to do today or tomorrow and are less inclined to engage in playful experimentation. Back then, art didn’t sell much, and it wasn’t talked about as extensively, so the fair was just fun. That’s when I started making toys. I had a resourceful helper in my department, Gyarasilal Mistry, a Rajasthani master mason. He’s no longer with us, but he was always willing to help with any idea I had. I would make model pieces and ask him to produce more, which he did. I also made puppets from old socks and clay toys, and working with clay led me to explore terracotta. One thing naturally led to another.

MN: So, did your terracotta work evolve from your experience making clay toys?

KGS: Yes, in a sense, the kind of terracotta work I do is rooted in the initial clay toys I made. While creating those toys, I realised that by forming a framework and placing a thin sheet of clay over it, the clay acted like skin over bones. This insight led me to think about working with clay in a more figurative way. So, one thing led to another. Apart from practice pieces, the first terracotta relief work I created was a depiction of a hunter and his trophies — like tiger skins — all made in clay. The hunter resembled those in old photographs, where they’d pose with animal skins and rupee notes poking out of their pockets. I made that piece around 1970.

After that, more incidental work followed. And a major flood hit Baroda. Not like the recent floods we’ve had here, but still quite severe. It submerged many villages around Baroda. Our faculty, teachers, and students were all very anxious to go and serve the public. So, they went to assess the damage and determine how they could be helpful. The local papers were full of photographs of bloated bodies of men and women. In fact, the Baroda papers, which hardly ever carried any photographs, were filled with them.

MN: Yeah, we do! (laughs)

KGS: Then, and of course it’s true sometimes, when a lean person gets submerged in water and bloats up, he can look healthier than he did before. In any case, one morning I saw one of these papers, which carried a whole lot of photographs showing bodies being mauled by dogs and other things. They wanted to show that the government was not idle. The Chief Minister at that time, I think, was Hitendra Desai, and they wanted to print his photograph in the corner. Unfortunately, the Press didn’t get a photograph that suited the theme, so Hitendra Desai was laughing away.

When I saw that, my theme shifted from the hunter and the trophy to how people can be quite insensitive to the suffering of others. Even when they try to help, they often think more about their own image than the distress around them. Then, at the same time, there was the Bangladesh war. So, the theme of the hunter and the trophy got projected into that context. The suffering public of Bangladesh and generals flaunting their medals and seeking fame... This whole series of events shifted from a rather innocent theme to a more loaded one. I can only work like that. Unless something specific or a special issue pushes me, I just sit back.

MN: So everything that you’ve done is connected in this…

KGS: In this sort of way, in the way of language of expression.

MN: Could you talk about the children’s books and the illustrations that went with it?

KGS: That was incidental to building up our department. In fact, when I was the dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts at MSU, we had a graphic arts department — it is still active and doing good work. Dhumal, the current Head of the Department, is married to one of my former students, who recently retired as the Head of the Department of Painting. Now, at that time, I thought one way art could influence public vision was through well-produced literature. So, I initiated a programme for well-designed book production aimed at reaching children, adults, and even the elderly through suitable literature. I had them put together a course on book production, but initially, there were no takers.

So, I went into the studio and started working on these books myself. The few books I produced also had an issue behind them. That year, Baroda experienced a communal riot after many years — though now it’s part of Gujarat’s history. I believe it was around 1969. This small riot affected many local shop owners on both sides. We decided to raise some money during a mela to help those affected. Although the amount raised wasn’t substantial, we thought it was a meaningful gesture. My first book was related to this. It wasn’t intended to be didactic, preaching that “fighting is bad, we are all brothers.”

Instead, I created a story about how, when God first made man, everyone looked alike. This led to confusion, where one person would mistake another for someone else. So, God provided them with a shop full of costumes. As they wore these costumes, their mannerisms and behaviour changed, making them different from each other. Over time, small animosities arose, leading to conflicts. The story’s moral was that while costumes may influence your actions, remembering that everyone was once the same can be beneficial. I also created books addressing issues like pollution in Baroda. I produced two or three books at that time, and although a few colleagues tried their hand at book-making, only one was particularly talented but didn’t pursue it further. Unfortunately, the department struggled to attract students, as many questioned the practical utility of designing books.

MN: But now bookmaking is an art by itself!

KGS: I know, that’s right! So… the great pity is that we always seemed to think a little too early about things (chuckles). Anyway, the whole issue is that thereafter, whenever there was a mela and I was around, they used to ask me to do one or two more books. So, I’ve done seven or eight books of that kind, and several of them have been published by Seagull Publishers. Otherwise, nobody was interested.

The children’s books… they had an exhibition and seminar here during Children’s Year. They looked at the book, and in fact, one of the people thought it should be presented to the committee there. It was Laxman’s wife who took it. She was told, ‘Oh, it has no colour, how will the children look at black and white?’ People already have certain preconceived notions, and it’s very difficult to change them. Most literature used to have black-and-white images at one time, and those stories, like Shakespeare’s, still remain.”

KG Subramanyan, Maquette for the Mural, War of the Relics, Paper cutout and gouache on paper

MN: Grimm’s fairy tales… all of them have black-and-whites images.

KGS: Yeah, but now they are more informed, so that’s what they think. This is the issue. In a sense, the idea of infiltrating these spheres wasn’t really mine. That grew with the rise of places like Santiniketan. Because the first person to create interesting illustrations for children was… well… Rabindranath Tagore wrote for children, and Nandalal Bose did those delightful linocuts for his works, which are still considered masterpieces. To some extent, I got my enthusiasm for doing this from that exposure.

But anyway, the point is, there’s so much one can do, and now one or two of our younger students are doing excellent work. In fact, Indrapramit, who teaches here at the college, has done some illustrations for an international agency. His father, Kumar Rai, is now the head of the Bahurupi theatre unit. At one time, Shambhu Mitra was, but now his assistant, Kumar Rai, leads it. Indrapramit is Kumar Rai’s son, and he has apparently done some notable work. So, there are people doing it. But in Bengal, especially, it seems that literary figures have taken it upon themselves to write for children, while artists have not taken it upon themselves to illustrate for children or to inspire them with the kind of work they can produce. Whether this is good or bad, I don’t know.

MN: In a lot of your paintings, there’s a rich use of colour… Can you talk about that?

KGS: Hmmm. That’s something I can’t comment on too much, because each person’s use of colour is, to a certain extent, related to their individual vision. In fact, at one time, most people used to say my paintings didn’t have much colour. (laughs) Back then, I probably worked a lot with what I considered ‘colourful greys.’ But people thought it wasn’t colourful enough. Later, of course, I began using colour more deliberately, experimenting with contrasts and such.

To some degree, it depends on the mood of the moment and the theme I’m working with. My colour is often notional — it doesn’t always correspond to seen reality. When I use a set of colours, I treat them like an alphabet; they come together to form their own language. As you combine them, and they gain a certain coherence, you create a language of colour. I suppose people today can understand that better, especially since now you can do all sorts of things. With computers, you can change a red image to a green one, or mix colours in different ways, and it makes sense. At one time, people felt the need to explain why Expressionists painted a green cow and a red cow together. It sounds silly now, but back then, it required justification. So, the use of colour is a kind of relative statement. Certain subjects require particular kinds of colours to heighten their emotional pitch or to bring it down. But none of this is meticulously planned — it just happens that way.

MN: In a lot of paintings I’ve seen, there are a lot of goddess-like figures with multiple hands and things like that. You know The Fairytale…Can you talk about that?

KGS: Well, I can’t talk about that in depth here because I’ve written about it before. There are two main points. One concerns what you see as a narrative. You see, at one time, people thought that when you painted, you simply captured what you saw. That means you would freeze reality, capturing it just as it is. But when you do that, reality becomes static, a mere thing. Now, suppose a writer were to describe this garden. The writer wouldn’t freeze reality in the same way. They would describe it bit by bit: the grass, the colour of the grass, the earth peeking through, the insects crawling, the water seeping in. All those little details build a narrative. Many paintings, too, are narratives of a kind — not necessarily storytelling but descriptive narratives.

Then there’s another issue: when you think about mythological figures, where does mythology come from? Mythology is born from people’s interpretations of certain experiences. For example, there’s a painting currently being shown in the United States called The Black Boy Fights With The Demons. In Santiniketan, we had a gardener who worked as a caretaker, and his daughter had a little black son. He was beautiful when he was born, and everyone admired him. But as he grew up, he began to throw stones at passing cars and run after cows — doing all the things Krishna supposedly did in myth, like throwing stones at carts, what we call ‘chakatasuravart.’ He would fight with insects and chase birds. These simple, everyday acts are often exaggerated into mythical narratives, similar to what happens in the stories of gods.

Similarly, when using the mother goddess figure, the complexity of the symbol is often overlooked. The newspapers simplify it, portraying the mother goddess as a symbol of good triumphing over evil. But it’s not that simple. One of my friends has studied the mother goddess myths in depth, and many of them verge on the macabre. The figure of the mother goddess can represent something as dark as a female figure devouring the male — like how certain insects behave. Not every mother goddess is depicted that way, though. There are other representations, like the Great Mother with many children clinging to her and her numerous breasts.

MN: Like Kali?

KGS: Kali, the mother goddess, is often associated with the charnel grounds, embodying destruction and death. Then there’s Durga, the mother goddess who, especially in Bengal, is also seen as the daughter of the household — a blend of the sensuous and the fearsome. I think I’ve written about this in an exhibition catalogue in Calcutta, on the theme of what is called Bahurupi. This Bahurupi tradition exists all over India. Certain castes dress up as either mythological or non-mythological characters and roam around. Their disguises aren’t complete; they don’t fully transform into these mythic beings. Instead, they reveal themselves as ordinary, sometimes lowly, human beings, acting out something that lies between the seen and the unseen, the ordinary and the beyond.

Whenever I use a mythological image, it’s like an act of dissection to understand what lies inside it, what the deeper meaning is. I believe that this approach can help people move beyond rigid, dogmatic interpretations — like thinking ‘Kali means this’ or ‘Durga means that,’ or even ‘Allah means this.’ These images are projections of something deeper within human beings. They reflect an awareness of one’s strengths and failings, and the attempts to create strategies to overcome these challenges. That’s where these images emerge from, at least in the way my mind works. So, that’s that.

MN: So, it’s from our… our collective consciousness?

KGS: That may be… Aaah, that’s a big word.

MN: (laughs) Also, could you talk about your reverse paintings?

KGS: There was a student of mine here, Ushakant Mehta, who might still be around somewhere. He has a house in Baroda, though he’s not seen much these days. He started collecting various glass paintings from different parts of Gujarat. This exposed me to a particular kind of painting that is immediate and spectacular, where even small things are made to look grand. That got me thinking — why not give it a try? I wasn’t entirely sure of the traditional method of glass painting, so I used gouache and backed it with oils, and it worked quite well. That’s how it all began. Since then, I’ve created all sorts of large works using this technique, though I now use transparent plastic instead of glass.

Page

Donate Now

More from Arts

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

Good paintings but can I also do like your paintings for my exhibition?

Shivanjali Vrushali

Apr 27, 2025 at 00:03