Deepa Mehta tells the story of a transwoman Sirat Taneja in her documentary I Am Sirat

Oscar-nominated filmmaker Deepa Mehta discusses how her films highlight socio-political realities, and underlines that every film requires a different approach, technically or emotionally. Her latest documentary, I Am Sirat, showcases the life of transwoman Sirat Taneja and explores themes of duty, obligation, and self-determination.

The private can be political, and in the virtual age, the humble phone camera can be wielded alongside powerful documentary-style film cameras to make a statement on a socio-political reality. “Good cinema is always political,” says Oscar-nominated filmmaker Deepa Mehta (73), who has always given a voice, and visibility, to issues like gender, marginality and human rights, from the days of Fire (1998) to her latest documentary, I Am Sirat (2023). The documentary was screened at the I View World Salon in Delhi recently. Dressed in earthy tones and framed by a salt-and-pepper mane, Mehta offered her insights and discussed the film.

Earlier, Engendered, a transnational arts and human rights organisation with special focus on gender equality and unalienable rights, organised the New Delhi Premiere of Oscar-nominated filmmaker’s acclaimed, poignant and layered documentary at the CD Deshmukh Auditorium, India International Centre, on May 14. The film first opened at Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) 2023 and was screened in competition at BFI London Film Festival 2023, but having it screened in India, to which the film is endemic, brings a layer of understanding and empathy to the film.

Mehta’s camera follows transwoman Sirat Taneja, the co-director of the film, documenting her pressures of being caught between duty and self-determination. Taneja has to revert to her ‘unwanted’ male identity when she has to take care of her ailing mother in New Delhi. Engendered screened the film in collaboration with the Embassy of The Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Embassy of Belgium in their ongoing roles as the EU Gender Champions. The screening was accompanied by a conversation with Mehta and Sirat, the protagonist of the documentary. Myna Mukherjee, the founder-director of Engendered, was also present. The I View World Salon Series is designed to increase awareness around gender and marginality, using cinema.

Taneja, who also spoke at the screening, is steadfast in her belief that trans roles in cinema should be owned by trans actors, waving the flag for the density of talent within her community and championing equal opportunities. “The trans-community is brimming with talent. We have actors, chefs, lawyers, doctors, models and more — and we should all get the same opportunities to get ahead,” she said.

Engendered travelled to Mumbai to screen Mehta’s Funny Boy — an adaptation of Sri Lankan writer Shyam Selvadurai’s 1994 novel of the same name, which tells the story of a young boy, who falls in love with his male classmate, even as political tensions escalate between the Sinhalese and Tamils in the years leading up to the 1983 uprisings — at an evening organized with The Quorum. Interestingly, Funny Boy premiered at Delhi’s I View in 2020. The intention is clearly to use the energy generated by the screenings to continue the dialogue of human rights for the marginalized. Though Netflix in India refused to screen both I Am Sirat and Funny Boy, human Rights will continue to find spaces to voice its struggle. Besides the observations at the panel, we got an exclusive interview with Mehta. Excerpts:

How long have you been with Sirat, absorbing her life and its challenges?

I have known Sirat for around four years. We worked together on the Netflix series Leila and I first got to know her during the intensive workshops we did for the series. The workshops (conducted by the brilliant theatre director Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry) are about exploration of character. Sirat, who plays a transgender guard, was so amazingly honest about her struggles and how she was trying to deal with them that she left me gobsmacked. The particular nature of her turmoil, and its universal resonance, deeply moved me. It’s about the tussle between duty, obligation, and self-determination. The entirely humane and unaffected way she grappled with it was both touching and unique. The blend of pathos and humour she brought to her situation is rare. We became friends and have stayed in touch since then.

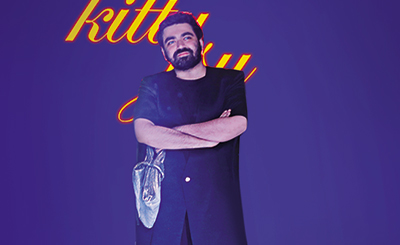

Sirat Taneja in I Am Sirat

Tell us about the role of music — both recorded music played and sung by Sirat — which literally carries forward the narrative of the film.

Indeed, music and poetry often have a very important and often poignant role to play in cinema, especially in the South Asian context. Besides all the songs chosen by Sirat, I wanted to end with the poem by Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Hum Dekhenge, which Sirat recites and sings in her very strong and intimate manner because those lines are eternal: they embody the struggle and challenges faced by women, who are often called selfish when they want to pursue their rights. (An interesting fact: In 1985, a decree by General Zia-ul-Haq prohibited women from wearing sarees. Pakistan’s world-renowned singer Iqbal Bano, clad in a black saree, protested against the decree by singing this nazm of Faiz Ahmed Faiz in front of a crowd of 50,000 in a Lahore stadium. The stadium echoed with chants of ‘Inqilaab Zindabad’.)

As a filmmaker how did you carve out the narrative from the everyday? How did you balance the harsh reality with those wonderful moments of reprieve — poetry and songs?

The narrative arc of the documentary is the everyday. Seen through Sirat’s lens, it’s built around her everyday existence. A series of amalgamations between tough moments and moments of joy. I think she does an Instagram reel at least once a week, which reflects the main emotion of the day.

How did this experience of documenting Sirat’s life perhaps alter the way you approach Cinema—with the inclusion of the phone snippets and that which was shot with camera?

The experience of documenting Sirat’s life in the way we did was entirely based on the practical nature of the shoot. I felt being surrounded by a film crew would inhibit the reality of her life. However, she chose to expose it. Every film requires a different approach technically or emotionally. This was a unique experience. The next film I will be doing has a crew of around 100 people.

Tell us a little about your upcoming projects, and how would you continue to highlight the voice of the marginalised?

I really think being marginalized does not necessarily belong to a certain group of people. We still live in a patriarchal society. Women are generally marginalized; there are discriminations on the basis of caste and religion. The small steps being taken by the LGBTQ+ folks are so very essential because theirs is the obvious lead many of us will and should follow. ‘Acceptance of all’ is the only mantra worth following — a tough but essential one. I am doing a feature called Forgiveness, based on the fallout during and after World War II in Canada, where all its Japanese nationals were placed in internment camps.

More from Culture

Comments

*Comments will be moderated